Eastern Mediterranean

The Old Testament disease category sara’at may include a wide variety of skin diseases and may also include what we recognise as modern day leprosy. Before 1980, no skeletal evidence had been found for leprosy in this region, but in 1980, several cases were reported from the Egyptian Dakhleh Oasis dating to the Hellenistic period (200 BCE) (Dzierzyzkray-Rogalski 1980). The skeletal remains were of Caucasians buried in a Nubian cemetery.

Zias has found skeletal evidence of leprosy in the Byzantine monasteries of the Judaean Desert, where people in need of asylum would seek shelter amongst the Byzantine desert communities (151). For example, the Monastery of Theodosius is one of the monasteries mentioned in ancient literature as sheltering people with leprosy. (Usener 1890) (150). Zias argues that at this time attitudes towards those suffering from leprosy changed. People were cared for instead of being shunned: “the Christian community now regarded those with certain illnesses like leprosy as having been chosen by God to suffer in this world in order to attain the world to come. To care for them, hospitals were established throughout the Mediterranean and monasteries were built in the Holy Land.” (150)

The Monastery of Saint John the Baptist, near the Jordan River was a traditional place for the washing of people with leprosy. Here Naaman, the commander of the Syrian army, was healed of his “leprosy” in the Jordan River (2 Kings 5), here too the Israelites’ forded the Jordan to enter into the Holy Land, and here Jesus was baptised by John the Baptist. These traditions add a certain sanctity to the site.

The Spread of Leprosy

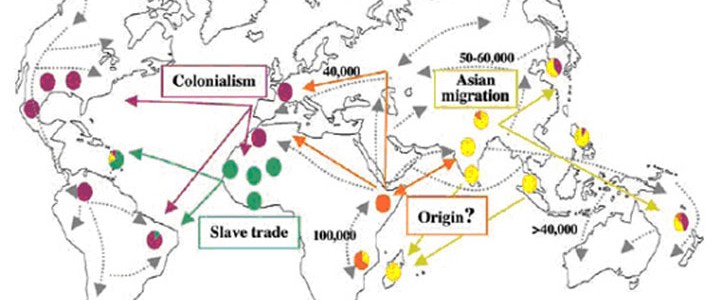

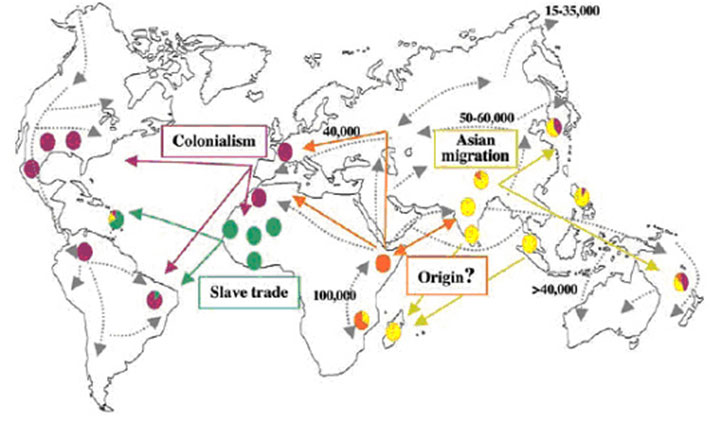

Samuel Mark argues against the theory that Alexander’s troops contracted leprosy in India between 327-326 BC and brought it back to the Mediterranean. This theory of the spread of leprosy by Alexander the Great’s soldiers was originally proposed by Johs Andersen in 1969. (He also argued that Pompey’s army introduced leprosy after the campaign against the Mithridates of Pontus in 62 BC.) Instead Mark argues that cargo ships carrying young slaves from India to Egypt brought the disease to the Mediterranean world no earlier than 400 BCE. Mark argues that “the evidence suggests that leprosy did not exist in the Mediterranean region before the fourth century BCE and the four centuries from when it was first described to the time of Aretaeus is consistent with the time necessary for it to have spread, been observed, and described in relative detail.” (Samuel 300) No doubt further genetic analysis of the strains of M. leprae will eventually clarify these theories.

Islamic Responses to Leprosy (extracted from the work of Michael Dols)

Michael Dols argues that stigma was not so obviously attached to leprosy as in other societies. He attributes this to the loose organisation of Islamic societies in the Middle Ages. (892)

“The Islamic world seems to have inherited the earlier Arabic terminology for leprosy. The word judham was adopted for the disease, probably because the Arabic root has the sense of “to mutilate” or “to cut off” and is descriptive of the serious disfigurement that may occur in cases of lepromatous leprosy. Thus, ajdham may mean “mutilated”, having an arm or foot cut off, or “leper” and “leprous”. The use of this root strongly suggests that the lepromatous form of leprosy existed in pre-Islamic Arabia. The use of the term baras appears to be equally old; it is derived from an Arabic root that may mean “to be white or shiny”. Baras was definitely used to name leprosy, probably in its early stages or in its tuberculoid form, but may also have been applied to other skin disorders.” (893)

The first important figure in the history of the Arab world who probably suffered from some form of leprosy was Jadhimah al-Abrash or al-Waddah, the king of al-Hirah who played a role in the politics of Syria and Iraq in the second quarter of the third century AD. There are also two famous pre-Islamic poets who may have had leprosy: Abid ibn al-Abras and al-Hārith ibn Hillizah al-Yashkuri, who wrote the seventh of the Mu’allaqāt. He recited the poem behind hangings so that the king would not be exposed to the sight of his disease, but Amr ibn Hind ordered the hangings to be removed because of his talent.

From Islamic times, in two places the Qur’an mentions the healing of those with leprosy (al-abras) by Jesus. Pious sayings about leprosy attributed to the prophet are as follows: “a Muslim should flee from the leper as he would flee from the lion” and “a healthy person should not associate with lepers for a prolonged period and should keep a spear’s distance from them” (895).

He also argues that there was a degree of ambivalence towards becoming infected. It was both reputed to be transmitted by humans and also inflicted by God. Islamic doctors inheriting the Galenic tradition held a humoral interpretation of the disease. They did advance the description of the disease, “particularly in their accounts of skin lesions and neurological symptoms”. Essentially, “the Arabic medical descriptions of leprosy were transmitted to medieval Europe and served as the basis of Western understanding of the disease until the seventeenth century.” (897)

Dols also describes how the Christian population in the region established xenodochia — houses for pilgrims and orphans, the poor and the diseased throughout the Byzantine Empire before the Arab conquests: “A number of early hospices made accommodation especially for lepers, or what were believed to be so. The famous hospital complex created by St. Basil in Caesarea in Cappadocia (A.D. 369-72) contained a leprosarium. Bishop Nona built a leper house in Edessa in the mid-fifth century A.D. and the very early hospital of St. Zotikos in Constantinople had been transformed into a leprosarium by the mid-sixth century A.D. According to Procopius, Justinian constructed xenodochia in Antioch, Jerusalem, and Jericho in A.D. 535. Slightly later, baths were erected for lepers outside the city of Scythopolis (Baysiin) because lepers were forbidden by Byzantine law to enter the forum or to use the public baths, as we learn from John Chrysostom (c. A.D. 347-407).” (900-1)

In early Islamic history, the governor of Egypt, ‘Abd al-‘Aziz (d. 85/704), the son of the Umayyad caliph Marwan, may have had leprosy, for he is described as having “lion-sickness.” Dols explains “This was a common euphemism for leprosy (judhim) and can be traced back to the description of leprosy by Aretaeus of Cappadocia in the second century A.D. The leonine appearance of the leper is caused primarily by the loss of the eyebrows and the swelling and toughening of the face. ‘Abd al-‘Aziz was given many medications for the ailment, but they were ineffective. Therefore, his physicians advised him to move to Hulwtin because of its sulfurous springs, and he built his residence there (903).”

In the twentieth century, people were still being diagnosed with the disease in the Arabian Peninsula, but only a few cases except for the south. Around Taiz in Yemen, there were villages with six or seven people in a single family with leprosy. The Aden Protectorate and Oman were the same. (Storm; Muir)

Today, the Eastern Mediterranean Region still reports a small number of cases, although the presence of the disease has reached WHO elimination levels everywhere except in South Sudan, while districts within countries such as Sudan, Egypt and Yemen still report between 300 and 900 cases every year. (WHO EMRO)

Leprosy is still endemic in several districts in twelve regions of Afghanistan.*2

Notes

*1 Countries in the WHO Region are Afghanistan, Bahrain, Djibouti, Egypt, Iran (Islamic Republic of), Iraq, Jordan, Kuwait, Lebanon, Libya, Morocco, Oman, Pakistan, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Somalia, Sudan, Syrian Arab Republic, Tunisia, United Arab Emirates, Yemen.

*2 http://www.emro.who.int/afg/programmes/leprosy-elimination.html

Sources

A Asilian, G Faghihi, A Momeni, M R Radan, M Meghdadi, and F Shariati, Correspondence to the Editor, International Journal of Leprosy 73.2 (2005):129-30.

Michael W Dols, “The Leper in Medieval Islamic Society” Speculum 58.4 (October 1983): 891-916.

T Dzierzykray-Rogalski, “Paleopathology of the Ptolemaic Inhabitants of Dakhleh Oasis (Egypt)”, Journal of Human Evolution 9 (1980): 71-74.

Mohamed Abdel Khalik El Dalgamouni, “The Antileprosy Campaign in Egypt” 6.1 (1938):1-10.

Samuel Mark, “Alexander the Great, Seafaring, and the Spread of Leprosy” 57 (2002): 285-311.

“Resolutions and Reports of the International Congress of Leprosy Held in Cairo March 21st-27th, 1938” Reprinted from The Journal of the Egyptian Medical Association” 31.3 (March 1938).

H W Storm, “Leper Survey of the Arabian Peninsula” Leprosy Review 10 (1939): 85-88, cited in World Wide Distribution and Prevalence of Leprosy Supplement to International Journal of Leprosy 12 (1944): 13.

Joseph Zias, “Current Archaeological Research in Israel: Death and Disease in Ancient Israel”,

The Biblical Archaeologist, 54.3 (1991): 146-159.

WHO Eastern Mediterranean Region Office (EMRO) http://www.emro.who.int/health-topics/leprosy/index.html