India

Origins of Leprosy in India

In India, the Sushruta Samhita and the Charaka Samhita (dating from 600 BC and 300 BC respectively) both refer to leprosy. All diseases were divided into eleven classes and leprosy was the tenth of fifteen categories of disease in the second class.

Diseases were understood to have both moral and material causes, and leprosy could be caused by either. Moral causes of leprosy could be as diverse as stealing, infidelity, disbelief in the existence of God and disrespect for His property, abuse of men and killing of women. Material causes of leprosy were attributed to a loss of equilibrium in the functions of the body, as expressed below:

Owing to several defects (dóshás) in the functions of the body, váyu (air), pitta (bile) and sléshma (phlegm) become deranged or lose their equilibrium, and the dhátus (or essential parts), namely, skin, flesh, blood, semen, and laskia (fat?) become deranged in their turn. Leprosy is the result of the combined action of all the defects (dóshás) and never of any one of them. The different kinds of leprosy are the result of the different manifestations of these defects. (Pandit N Bashya Charya)

Wellesley Bailey and the Mission to Lepers, India

Alice Grahame

The founder of the Mission to Lepers was an Irishman, Wellesley Bailey, who had gone to New Zealand and New Caledonia unsuccessfully looking for gold and then went on to India in the hope of taking a police commission. Instead he began teaching in a mission school with the American Presbyterian Mission in Ambala where he was introduced to a small leprosy settlement close by. (Gussow, 205) In his own words,

The asylum consisted of three rows of huts under some trees. In front of one row the inmates had assembled for worship. They were in all stages of the malady, very terrible to look upon, with a sad, woebegone expression on their faces – a look of utter helplessness. I almost shuddered, yet I was at the time fascinated, and I felt, if ever there was a Christ-like work in this world it was to go among these poor sufferers and bring to them the consolation of the Gospel. (Miller 11)

Bailey’s wife to be, Alice Grahame, shared his letters with her three Dublin friends, the Misses Pim, and on Bailey’s return to Ireland in 1874, Charlotte Pim began to organise small meetings in her drawing room in order to describe “the terrible condition of [the people], physically, mentally, spiritually, and of what we were trying to do, for just a few of them, at Ambala, in the Punjab.” (Cited in Gussow, 205)

They produced a sixteen page pamphlet to spread their appeal. They called it the original beggar because “its circulation among Dublin and other friends resulted in the awakening of immediate interest and the beginning of practical help.” It drew support from women in Ireland and unprecedented support from groups all over the UK.

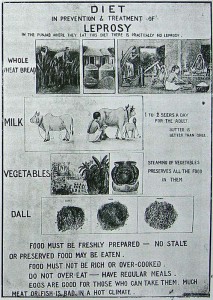

Diet Chart

In 1889, having raised ₤1 628, the Mission was able to assist twenty-two stations in India and Ceylon. By 1924 there had raised over one million pounds sterling and were working in cooperation with nineteen British, sixteen American, and three European Protestant societies. (Gussow 206)

In 1920, the Mission to Lepers held a large conference in Calcutta where superintendents of the various asylums gathered to discuss their work. (Report 1920) By then, there were more than 8 850 people in leprosy asylums. *1

At the conference, Reverend Frank Oldrieve told those gathered that their appeal had received Rs 1, 860, 000 from India, about 70 per cent of which had been given by Indians. The mission now had a medical subcommittee that espoused chaulmoogra oil-based injections, developed by Sir Leonard Rogers. The Mission was also actively lobbying the government to detain “pauper lepers”.

The National Leprosy Fund and the Indian Leprosy Commission

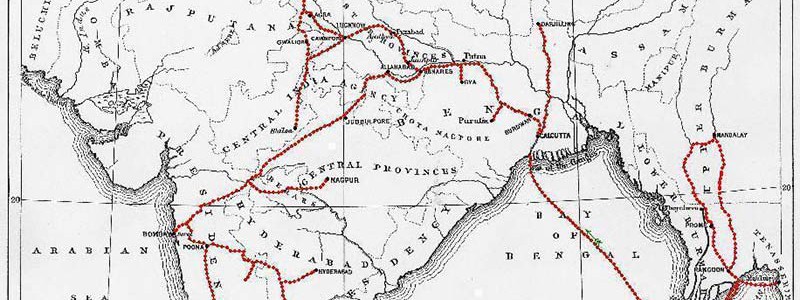

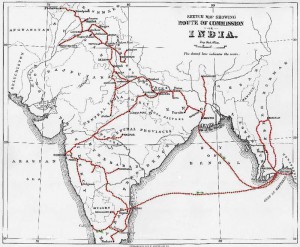

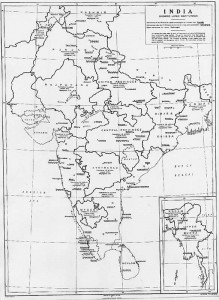

Route of Leprosy Commission in India, 1890

The National Leprosy Fund was initially established as the Committee for the Father Damien Memorial Fund in order to pay tribute to the life and personal sacrifice of Father Damien de Veuster. Its distinguished members included the Archbishop of Canterbury, the Duke of Norfolk, Lord Randolph Churchill, Baron Ferdinand de Rothschild, the Bishop of London, Sir William Jenner, and the Hon G. Curzon, as well as prominent members of the medical fraternity. The executive committee decided to erect a memorial to Damien at Molokai, site of the leprosy colony in Hawaii; to establish a fund for people with leprosy in the United Kingdom; to endow two studentships for doctors to study the disease; and to appoint an Indian Leprosy Commission to investigate leprosy in India.

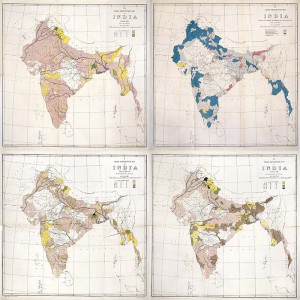

Various maps of leprosy in India produced by the Leprosy Commission

The Investigation Commission departed for India on October 23, 1890 and arrived at Bombay on November 17. After extensive surveys and investigations, the commissioners concluded that leprosy was a disease sui generis, originating de novo from a sequence or concurrence of causes and conditions that were related to each other in as yet unknown ways. (Leprosy in India 1890-91)

Many members of the National Leprosy Fund were very disappointed that the commissioners did not wholeheartedly recommend compulsory segregation, so they overruled several of the commission’s conclusions, appending recommendations for segregation.

British Empire Leprosy Relief Association (BELRA)

Sir Leonard Rogers

Like the National Leprosy Fund of the 1890s, BELRA enlisted the support of many powerful and influential members of British society. The patron was HRH the Prince of Wales. Support came from the Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs, the Secretary of State for the Colonies, the Secretary of State for India, the Viceroy of India, and the Governor Generals of Canada, South Africa, and New Zealand. The chairman of the General Committee was Viscount Chelmsford, the late Viceroy of India; the chairman of the executive committee was Sir Edward Gait (member of the India Council), and the chairman of the medical committee was Sir J Rose Bradford.

The three more active members of the association were the Hon Medical Secretary Sir Leonard Rogers (1868-1962), of the Indian Medical Service, professor of pathology at the Calcutta Medical College who founded the Calcutta School of Tropical Medicine, in 1921; the Honourable Treasurer Sir Frank Carter, a well-known philanthropist and benefactor to many of Sir Leonard’s fundraising schemes; and the Secretary Rev Frank Oldrieve, the Secretary for India of the Mission to Lepers. (Allen)

Chaulmoogra plant

Appeal for funds were sent to the colonies under the title “The British Empire Leprosy Relief Association” (BELRA) accompanied by the manifesto “To stamp out leprosy in the British Empire: A Great Campaign”. BELRA claimed that there were more people affected by leprosy under the flag of the British Empire than any other:

For India 200 000 is a moderate estimate. The British tropical African Colonies, Nigeria, Kenya, Uganda, Tanganyika, and Nyasaland, probably have from 70 000 to 80 000 cases. The disease prevails in varying degrees in South Africa, the West Indies, Ceylon, the Malay States, Mauritius, Malta, and Cyprus. Altogether there are considerably more than 300 000 lepers in the Dominions of the King.

Robert Cochrane’s leprosy survey of India, 1929

This new association was energised by Sir Leonard Roger’s hopes of treatment using a hydnocarpus preparation. BELRA aimed to house those who were homeless and destitute; to supply the latest medical information and the most improved drugs to leprosy institutions, settlements, and hospital clinics; to train people to apply treatment efficiently; and to support sound schemes of segregation, with the best treatment. They entertained both benevolent and epidemiological and medical objectives. They resolved to collect information and statistics and to issue bulletins of information and advice to all workers in the field, as well as supporting further research into the aetiology and treatment. (Worboys, “Mission and Mandate”)

The Gandhi Memorial Leprosy Foundation

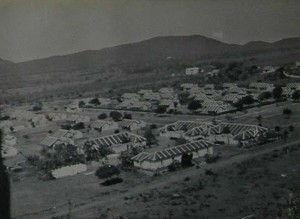

Central Leprosy Teaching and Research Institute, Chingleput, South India (CLTRI)

The first really concerted indigenous Indian activity against leprosy took place almost simultaneously with Indian independence and the establishment of the Gandhi Memorial Leprosy Foundation. Gandhi’s visits to leprosy asylums (such as Cuttack in 1925 and 1927, Chandkhuri in 1933, and Purulia in 1925 and 1934) and his relationship with Parchure Shastri, which began at Yeravada prison in 1932 and was taken up again in 1939 at his ashram in Sevagram, became part of the mythology of his focus on leprosy as an index of attention to the wellbeing of the nation. Gandhi had included leprosy in his eighteen-point constructive program. For him leprosy and the care of people with leprosy was an index of the health of the body politic: “If India was pulsating with new life, if we were all in earnest about winning independence in the quickest manner by truthful and non-violent means, there would not be a leper or beggar in India uncared for and unaccounted for.” (quoted in Mehendale) As David Arnold puts it, Gandhi thought that “the Indian ‘body politic’ had become ‘weak’ and ‘diseased’ and unable to resist the attack of ‘foreign bodies’. In order to restore his country to health, Gandhi offered “an individual but highly emblematic decolonisation of the body.” (285) Inspired by his example, in 1951, the Gandhi Smarak Nidhi decided to undertake leprosy work, and in 1952, the Samiti was renamed the Gandhi Memorial Trust. The annual report for 1952 expressed a sense of purpose and national responsibility for leprosy: “now that the knowledge about leprosy has advanced and our country has become independent, we shall have to look at this problem from the humanitarian as well as the national point of view.” This beginning coincided with the use of the sulphones. The Gandhi Memorial Leprosy Foundation (GMLF) was responsible for working with the Government to introduce leprosy work at a national level.

Ward at CLTRI, Chingleput

By the mid-1980s, leprosy work in India had gone through several phases. After the All India Leprosy Workers’ Conferences, the GMLF began village-based work and also collaborated with the Government of India in developing successive national leprosy programmes. Then in 1981, Indira Gandhi commissioned a leprosy eradication strategy. She commissioned the Swaminathan working group on the eradication of leprosy in India which aimed to arrest the disease in all leprosy cases by the turn of the century. With the advent of multidrug therapy, the National Leprosy Eradication Programme (NLEP) aimed to treat all leprosy cases with MDT by the year 2000 in order to minimize transmission of the infection. (Rao 95)

Entrance to CLTRI, Chingleput

Although the implementation of MDT began in India using the full vertical leprosy infrastructure, several innovative State level campaigns set the pattern for the Indian leprosy programme. All people diagnosed with leprosy in three highly endemic districts, with a prevalence of 10 per 1000 in a population of two million, received combined chemotherapy in 1983. (Rao 95) Leprosy control was integrated with primary health care when the leprosy prevalence rate reached two or less per 1000.

There is some debate and a great deal of anxiety today about the continuing presence of leprosy in India. Research conducted of 804,536 people in 8 districts during 2009-2010 indicated that “large numbers of early leprosy cases do not reach the health facilities where leprosy treatment is provided, although some chronically ill patients reach late”. (A. Kumar and S. Husain)

Bankura

- O.A. Hospital, Bankura, 1979

- Bankura chapel, 1979

- The second storey at Bankura Leprosy Hospital houses the Teaching Laboratory, Classroom and Training Hostel. (TLMI Publicity Release, Sep 1991)

- Stanley Browne and ulcer treatment. Bankura clinic, 1970

Barabanki

- TLM Barabanki Hospital and out-patients’ entrance. (TLMI Publicity Release, March 1993)

Belgaum

- Going home: Belgaum, 1976

- Dr Gopal Dass examines a patient on a village survey. Mr Patole, paramedical supervisor, to left of Dr Dass. Belgaum

Calcutta

- Site for new hospital, Calcutta. (On front: Premananda Dispensary for Leprosy 1940; next door: Maniktalla Christian Cemetery)

- Patients and friends at TLM leprosy control clinic, Calcutta.

- Case detection survey in progress in a Calcutta slum. 2001

- TLM Premananda Memorial Leprosy Hospital.

Champa

- Male inmates, Champa. Front view of huts. November, 1903

- Mr and Mrs Penner with a group of leprosy patients, Champa. 1904

Chandag

- TLM’s ‘Mary Reed’ Leprosy Hospital, Chandag. Named after its founder. (TLMI Publicity Release, Mar 1993)

Chandkhuri

- Chandkhuri, 1931

- Chandkhuri, 1931

- Chandkhuri choir

- 1945 India Conference held at Chandkhuri

- Foreground: Untainted Home for Girls; Background: Women’s Ward with Church. 1915

- A protest in support of women’s literacy. Placard: ‘We do not want to remain illiterate’

- Boy scouts in Chandkhuri

- Chandkhuri Leper Home and Hospital, A Partial View from the North Side’ (undated)

Faizabad

- A young lepromatous patient studying, Faizabad. (TLMI Publicity Release, Mar 1993)

- Faizabad Leprosy Home: a leprosy patient undergoing treatment for contractual fingers after reconstructive surgery performed by Dr Silas Singh of Almora Leprosy Hospital. 1970

Kalimpong

- Patients at Kalimpong, West Bengal, India, 1934

Karigiri

- Map of Karigiri Leprosy Control Programme in the villages. 1975

- Artificial limb making and fitting, Karigiri

Nasik

- Rosalie Harvey demonstrating a practical way of washing ulcers using a bucket, hose and tap. Nasik, India. 1901

Poladpur

- Poladpur church, built by the leprosy patients. May 1905.

Notes

*1 In 1921, in the Indian census 102,503; In Orissa 10,596.

Sources

Irene Allen, LEPRA, Colchester, Essex, History of LEPRA.

David Arnold, Colonizing the Body: State Medicine and Epidemic Disease in Nineteenth-Century India, Berkeley: U of California P, 1993: 285.

Pandit N Bashya Charya, “Leprosy in Ancient India” The Adyar Library Series, No 2 Reprinted in The Theosophist: A Monthly Magazine of Oriental Philosophy, Art, Literature and Occultism Conducted by H S Olcott October 1889.

Zachary Gussow, Leprosy, Racism, and Public Health: Social Policy in Chronic Disease Control. Westview Press, 1989.

Anil Kumar and Sajid Husain, “The Burden of New Leprosy Cases in India: A Population-Based Survey in Two States” ISRN Tropical Medicine (2013) http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2013/329283

The Constructive Programme, its Meaning and Place in M. S. Mehendale, Gandhi Looks at Leprosy, (Bombay: Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan, 1971): 31.

Donald A Miller, An Inn Called Welcome. Mission to Lepers, 1965.

C K Rao, “Implementation of WHO MDT in India 1982-2001” in Multidrug Therapy Against Leprosy: Development and Implementation Over the Past Twenty-Five Years” (World Health Organisation: Geneva, 2004), p. 95

Report of a Conference of Leper Asylum Superintendents and Others on The Leper Problem in India, held in the Town Hall, Calcutta, from the 3rd to 6th February, 1920, under the auspices of the Mission to Lepers, Cuttack: Printed at the Orissa Mission Press, 1920.

Jo Robertson, ‘In Search of M Leprae: Medicine, Public Debate, Politics and the Leprosy Commission to India’, in Helen Gilbert and Leigh Dale (eds.) Economies of Representation: Colonialism and Commerce. UK: Ashgate, 2007.

—-, ‘Anxieties of Imperial Decay: Three Journeys in India’ in Helen Gilbert and Anna Johnston (eds.) In Transit: Travel, Text, Empire, NY: Peter Lang, 2002.

WHO, Regional Office for South East Asia, Regional Committee, Thirty-Fifth Session, “Annotated Agenda: 1. Leprosy: Problem, Strategy for Control and Operations” (SEA/RC35/5 Add. 1) 5 July 1982. p. 3

Worboys, Michael, “The Colonial World as Mission and Mandate: Leprosy and Empire, 1900-1940.” Osiris (2000): 207-218.

—–, “Was there a Bacteriological Revolution in Late Nineteenth-Century Medicine?” Studies in History and Philosophy of Science Part C: Studies in History and Philosophy of Biological and Biomedical Sciences 38.1 (2007): 20-42.