Leprosy and Empire

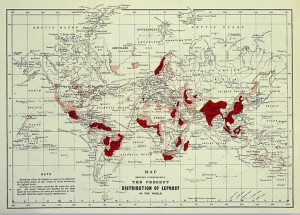

Map showing the distribution of leprosy around the world in 1891. Extracted from Leprosy by George Thin. (Wellcome Library, London. Licensed under CC BY 4.0)

Towards the end of the nineteenth century, debates about leprosy and its contagiousness focused upon its potential to stage a “return” commensurate with its activity in Europe in the past. These medical and popular debates sharpened in focus until they became debates about how to contain the contaminating agents at their point of origin and segregation in the colonies became the issue. Editorials in the British Medical Journal in November 1887, for example, expressed what must have been a growing concern about the threat of the disease. The editorials opposed, on the one hand, the views of those who argued that any proof of infection, however isolated, was sufficient cause for alarm, to those in a leading article in the Times newspaper that in tune with the conclusions of the Report on Leprosy by the Royal College of Physicians that the disease was no more contagious than syphilis, and compulsory detention was unnecessary. Another editorial in the same month noted that the question of the contagiousness of leprosy was a question uppermost in the thoughts of those in the medical establishment and in the Government. It reassured its readers that the prevalence of the disease amongst populations that are “under the care of the British Government” was being noted.

This concern was exacerbated in 1889 and 1890 by the unfortunate conjunction of a series of events: the death of the well-known Catholic priest, Father Damien, in the leper colony at Molokai, Hawaii; the discovery of leprosy in an Irishman who had never been out of the country (Hawtrey Benson, 1889, p. 860); an experiment upon a condemned criminal, Keanu, by Dr. Arning, at Molokai; and British and American alarm at the discovery of a leprous Swedish immigrant who had crossed the Atlantic undetected.

A flurry of attention was concentrated on the potential for an outbreak in Great Britain. An editorial in the British Medical Journal (1889) at the end of March, entitled ‘Leprosy in the United Kingdom,’ seeking to allay alarm, conceded with some justification that the subject had come to preoccupy both medical discussion and “the public mind.” It explained how the medical mind had been impressed with the discovery of the leprosy bacillus, with Arning’s experiment with Keanu, and how the popular imagination had been riveted by the death of Damien: “For these and other reasons the subject of leprosy has recently cropped up from time to time in magazines and newspapers, in addition to being a subject of discussion in medical journals” (Brit. Med. Journ., 1889, p. 721).

In their attempts to reassure, the editors of the British Medical Journal constantly reiterated that “leprosy is rarely seen in this country;” “cases of leprosy in this country are very uncommon;” “there is no evidence that the disease spreads by contagion in England;” “we are satisfied that there is no cause for alarm;” “we are satisfied that on the part of the general public there is no reason for fear or anxiety” (ibid, p. 722). In support of this editorial, the statistics of cases presented to the Dermatological Society in the United Kingdom were published in the same issue of the Journal (p. 734).

These efforts must not have defused public concern because a further editorial in June suggested that “the leprosy question is becoming one of the questions of the day” (Brit. Med. Journ., 1889, p. 1364). It welcomed public discussion in the hope that attention to “this great pest” would result in convincing governments that the disease was contagious and so lead to “enforcing compulsory segregation.”

Subsequent concern about the disease became increasingly focused on leprosy in the colonies. It began to be monitored with increasing attention and an eye to the possibility of its “coming home.” Examples of people with leprosy in India who were uncontrolled and uncontrollably spreading germs by sitting on iron railings outside a school attended by European children, selling fruit, and contaminating the wells of the city made it into the newspapers. Infected people were represented as interchangeable with the bacteria: “The Principal of St Xavier’s College stated that the lepers rubbed their sores against the iron railings surrounding the Elphinstone High School, and that the boys afterwards sat upon them” (Brit. Med. Journ., 1889, p. 1261). There was a call for additional powers so that the Health Department could “deal effectively with the evil” (ibid.) and a suggestion made that police powers could also be increased.

A letter to the Journal in June summarized the spirit of the times: the 1867 Report was “dangerous and full of false conclusions” and as a result “we are now threatened with it at home,” but “timely preventative measures in our Indian and Colonial possessions” will take care of the problem. “If we legislate in India and in the colonies, enough will be done; we shall check the disorder at the spring head” (Simms, 1889, p. 1491). One study presented sixteen cases which it used to develop an argument for “a system of precaution, of segregation… regulations influenced and dictated by a spirit of Christian charity,” and a “duty imperative upon England” to stamp out the disease (Donnet, 1889, pp. 301-5).

The push for legislation intensified, and South Africa and New South Wales enacted laws to detain those diagnosed with the disease. The Journal (1890, p. 1047) was full of praise for the measures enacted in these colonies: “the public of England would be making a very great mistake if they supposed, because they heard of isolated cases of leprosy in distant parts of the colony, that the matter was not being dealt with by the Government of the colony.” In fact, the article maintained that in no part of the world were such responsible measures being taken. Prompted by the discovery of several Europeans with the disease, a Leprosy Bill was passed in New South Wales with “promptitude and uncompromising thoroughness” on November 20, 1890 (Brit. Med. Journ., 1891, p. 779).

When the British Empire Leprosy Relief Association (BELRA) was formed three years later it sent out its appeal to the colonies showing three “before” and “after” photographs of treatment with the manifesto “To stamp out leprosy in the British Empire: A Great Campaign”. Its mission was to fight against “a loathsome and mutilating disease which, though now little known in the United Kingdom, takes heavy toll of the subjects of His Majesty overseas, where it spares no class or race.” This fight was an Imperial responsibility for there were more people with leprosy under the British flag than in any other Imperial outpost. This included 200 000 as a moderate estimate in India. The African Colonies of Nigeria, Kenya, Uganda, Tanganyika, and Nyassaland, were reckoned to have from 70 000 to 80 000 cases. The disease was also present in varying degrees in South Africa, the West Indies, Ceylon, the Malay States, Mauritius, Malta, and Cyprus. BELRA argued that there were more than 300 000 people with the disease “in the Dominions of the King”.

The first two annual reports of BELRA were published with the titles “A Problem of Empire Suffering” and “Some Questions of Empire Suffering”. The association saw itself working to treat leprosy-afflicted colonial bodies, but its rhetoric transfers the disease to the whole of the Imperial body politic: the Empire is suffering from leprosy. This echoes the vision of the founder of the Leprosy Mission, Wellesley Bailey who in his writings imagined leprosy as the means of bringing together members of the Empire. For him, the asylum became a little haven of heaven on earth, an alternative Empire; later still, as the Empire prepared to pass Indian responsibility for India back to the Indians, settlements were imagined as ideal colonies, indexes of the imperial project; but now, as the British Empire began to fragment, the Empire was imagined as suffering and corrupted and afflicted with leprosy.

In 1935, BELRA started a travelling exhibition designed to tour England so that people would learn of the work of the association and support it. Originally the exhibition was entitled “The Shadow on the Orient”. It could be set up in a large hall, and it portrayed the history of leprosy from earliest recorded times to the present. Apparently it featured a mock up hospital and an outpatients’ department, where people were treated. Full-sized models showed the progressive signs of the disease. Illuminated models depicted “Leprosy through the Ages” and “Landmarks of the Past” showed churches, lazar houses, and other buildings that represented the story of leprosy in England in the Middle Ages. There was even a film titled “A Stain on our Empire’s Flag” and an Oriental Market at which goods from the Far East were sold.

From 1935 until 1963, with a break for the war years, the exhibition seems to have been shown in some form or other. The accompanying booklet for 1948 is available and gives some idea of the form that the appeals in the interest of healing the Empire took after the war. The Secretary of State for the colonies wrote as an opening address:

I commend this exhibition to all who have the interests of the Colonies at heart. Here in the United Kingdom we long ago stamped out leprosy, but it remains a scourge to millions of our fellow citizens in the Empire. We are but discharging our responsibilities to them by seeking by all means within our power to alleviate their sufferings and to root out their affliction. In the battle, the British Empire Leprosy Relief Association is providing assistance of the first importance and its work deserves and demands the sympathy and practical contribution of every one of us. I wish the fullest measure of success to the appeal which the Association is now making.

Leprosy was in 1948, after the ravages of World War II, very squarely taken up as one of the responsibilities to the fellow citizens of Empire. The presence of the disease in the colonies was explained in terms of progress and civilisation – England had made progress and left behind the poor living and dietary conditions that permitted leprosy to flourish; hence the disease was no longer present. Once the colonies attained the same standards of civilisation, the disease would disappear there too. The viewers at the exhibition were told that: “Years and years of work lie ahead, requiring considerable finance, before the disease can be said to be under control. When that stage is reached, then, and only then, will it be possible to say that it is really being eliminated – as it has been in England.” (21)

A sculpture depicts two African figures, and the accompanying text provides the clue to their gestures:

Who walk alone … who tread life’s loneliest path, 2 000 000 British subjects, victims of the deadliest scourge on earth, their constant prayer, their deepest longing is for freedom, freedom from leprosy. To that end the British Empire Leprosy Relief Association has dedicated its services, resources, and fullest energies, to the healing of the sick and the eradication of the disease from the Empire.

Notes

I am indebted to Irene Allen from LEPRA for her interest in and passion for preserving the records of the organisation.

*1 The British Empire Leprosy Relief Association (BELRA) was formed three years later and two of the key personalities at that conference were essential to its formation: Sir Leonard Rogers and Rev Frank Oldrieve (Secretary for India of the Mission to Lepers). Sir Frank Carter, the third inaugural member, was a well-known philanthropist and benefactor to many of Sir Leonard’s fundraising schemes. Dr Muir, who was also at the conference in 1920, was to join them later.

Its beginnings seem very grand in comparison to the modest and domestic beginnings of the Mission to Lepers. The patron was HRH the Prince of Wales. The vice presidents represented both the Imperial centre and the colonies. There was the Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs, the Secretary of State for the Colonies, the Secretary of State for India, the Viceroy of India, and the Governor Generals of Canada, South Africa, and New Zealand. There were also Chairmen of the three committees of the association. The chairman of the General Committee was Viscount Chelmsford, the late Viceroy of India; the chairman of the executive committee was Sir Edward Gait (member of the India Council), and the chairman of the medical committee was Sir J Rose Bradford. It has representatives of the foreign office, the colonial office, and the India Office, and well as a representative of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine. The three more active members of the association were the Hon Medial Secretary Sir Leonard Rogers, the Honorable Treasurer Sir Frank Carter, and the Secretary Frank Oldrieve, and there was a distinguished list of titles in the general committee.