Going Places

Originally published in the WHO Goodwill Ambassador’s Newsletter for the Elimination of Leprosy, Issue No. 49 (April 2011). The information was correct and current at the time of publication.

Rambarai Sha has come a long way from a lonely hut by a river.

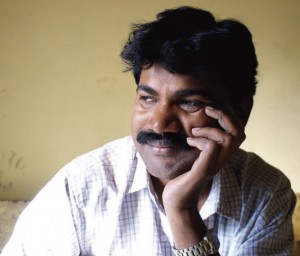

Rambarai Sha: people have set ideas about leprosy

On the wall of Rambarai Sha’s mother’s house hangs the cover of the June 2010 edition of the Goodwill Ambassador’s Newsletter. It features a photo of her son and two other activists presenting a petition to the deputy chief minister of India’s Bihar state. Neighbors stop by to admire the picture and comment that her son is going places.

There was a time when it seemed like Rambarai wouldn’t be going very far at all. At age 10 he became aware of a patch on his leg. He applied ointments and bandages to cover it up, but it wouldn’t go away. People began to talk and he went to a nearby hospital to be examined. The doctor diagnosed leprosy and said there was no cure.

Once his schoolmates got to hear of this, they refused to sit next him and he was consigned to the back of the classroom. “Everyone avoided me,” he recalled. Unable to focus on his studies, he dropped out. The head teacher told him not to return, and took the books and stationery he had paid for. “Nobody talked to me. Nobody played with me. My days were filled with tears.”

A month later, the village head came to his house, telling his parents that unless they sent their son away, the whole family would be ostracized. There was little choice. His father built him a hut about 1 kilometer away, by a river. For two years he lived there alone, begging by day and crying at night, fearful of ghosts.

One day a person affected by leprosy who had passed through the village begging for food came to the river to eat. He saw Rambarai’s leg and asked if he was receiving multidrug therapy. “But there is no cure!” the boy replied. His new acquaintance set him straight. Rambarai ran home to tell his parents, and the next day set off for the hospital he had been told about: Little Flower, in Raxaul, by the border with Nepal.

June 2010 edition of the Goodwill Ambassador’s Newsletter

A New Life Begins

Rambarai stayed on in Raxaul, joining a colony of people affected by the disease. At first he continued to subsist on begging; then he got work at Little Flower assisting in the construction of a new building. It was at Little Flower that he met his wife, the daughter of leprosy-affected parents, marrying her at 19. A hospital job followed, and he studied English in his spare time.

Thanks to money he made working as a guide in Nepal, he and his wife were able to open a shop. More recently, Rambarai has been supplementing this income by working as an insurance agent. The couple have two sons, and Rambarai attaches great importance to their education. One is at college in New Delhi, and the other is aiming to follow in his brother’s footsteps.

Rambarai’s experiences have helped others. “I think I was the first man in my village to have leprosy,” he says. “Later there were two more, but they continue to live at home. Now everyone in my village knows there is a cure for leprosy and that there is no need to send people away.”

Yet stigma remains the great enemy. “There are parts of Bihar where we won’t be served tea – even our children, which is the real problem.” But stigma, he acknowledges, is an issue the world over. “People have very set ideas about leprosy. Educated people know better, but here in Bihar, many people are not educated. Sometimes it is very hard to reason with them.”

Rambarai is increasingly involved in organized efforts to empower people affected by leprosy and break down social barriers. A chance encounter led to an introduction to the National Forum, the countrywide platform of people affected by leprosy, and the opportunity to attend a conference in Mumbai. Connecting with the forum, he says, opened up new horizons.

He also became one of the founding members of the Bihar Kustha Kalyan Mahasangh (BKKM), which has been playing an active role lobbying for improved pensions for people affected by leprosy in the state. Last year, he and fellow members conducted a survey of all 63 self-settled colonies in Bihar to present to state authorities.

Now he has assumed his biggest role yet: becoming one of the first nine trustees of the National Forum and helping to shape the future for people affected by leprosy. “It’s an amazing opportunity,” he says.

Rambarai Sha’s journey continues.