-

1926 Born in Maebashi, Gunma Prefecture.

1941 Entered National Sanatorium Kuryu Rakusenen.

2003 Died at age 77.

---

I was born in 1926, the year of transition from the Taisho era to the Showa era, in Maebashi. Our family had a watch business, and in 1932 we opened a store in Fujioka with several employees, and the business prospered. My father’s fingers were slightly bent, and it was probably because of the disease. When I was around eight, I started getting spots on my face, and I remember my grandmother saying that it was probably the same sickness as my father’s.

In 1940, my hardworking mother died. After that, a policeman would occasionally come to our store. He would come three or four times a week and urge my father to enter a sanatorium. The store also got fewer customers and business suffered, so we closed the store and moved to Yunozawa, a district in Kusatsu where many people affected by Hansen’s disease and their families lived. From around 1941, the government appealed to the residents of Yunozawa to disband and move to sanatoriums as well, and my father and I entered Kuryu Rakusenen together.

After we moved in we realized it was a sanatorium in name only, and was actually a place where people were forcibly interned. We had to cut and carry firewood, dig out and install wooden pipes to the hot spring, take care of seriously ill patients, and cremate them when they died. As a result, my hands and feet became increasingly numb and my health deteriorated rapidly. My father died just after the war, in a condition similar to starvation. My younger brother and youngest sister, who were not infected, entered the nursery attached to the sanatorium. Conditions in the nursery were bad, and they both became thin. Somehow, they finished their compulsory education there and went out into the world, but both of them struggled. My sister Hiroko was bullied, and returned to the sanatorium with only the clothes on her back. She got married at the sanatorium but committed suicide at age 26. I had no desire to live either, and attempted suicide twice, but did not succeed. I tried jumping off a cliff, and taking a large dose of sleeping pills with shochu liquor, but did not die.

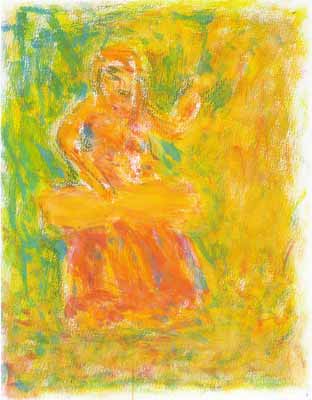

Around that time, I read about a female Jewish artist in a Nazi concentration camp. She taught children who had been sentenced to the gas chamber how to draw pictures, so that for even a moment these children could experience the joy of living and to give them hope. It said that two or three children had managed to escape. That was when I decided to start painting. I formed a painting club in the sanatorium, and volunteer teachers came to teach us, but we didn’t have one permanent teacher.

I did not marry, because sterilization is a humiliation that deprives a person of their fundamental feature of sex. When I was 47, after the requirement for sterilization was revoked, I married an older woman but it did not work out and we separated. We still see each other in the sanatorium and are friends, however.

I really wanted to experience love and to get married. I wanted children. I also wanted to study.

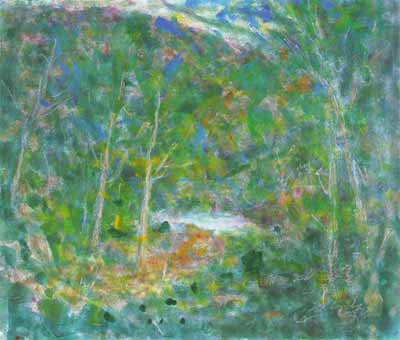

My other younger sister, Chiyo, took care of me at the sanatorium. As my eyesight became worse I could not go to the studio by myself, and she would take me. When I was ready to paint, she would put a plastic bag over my hand and fasten the brush with a belt. She would also clean up when I finished.

In 1973 my first submission to the Nika Art Exhibition was chosen for inclusion. This didn’t make big news within the sanatorium, but the head of the sanatorium, Dr. Kobayashi, was very happy and went to Ueno to see it. It is difficult to submit a work to the Nika exhibition and costs money, so I never submitted anything else and used the money to buy supplies instead. My works were selected 22 times in prefectural exhibitions, and one won a prize.

I paint from my heart. For me, painting pictures is proof that I am alive. It is my validation as a human being. Being a plaintiff in the trial was also a way to get back my humanity.

I did not expect the trial to be easy, and did not expect the verdict to be reached so quickly. I had lived an irregular life for so long, and I thought the next step would be difficult. The future is overwhelming – no matter how wide I open my arms I cannot embrace everything. I had no idea that such a wonderful world existed.

I’ve been painting pictures for a long time, but I didn’t think I would be able to publish a collection. I am happy beyond words for the help I had in making this book. Although I am inexperienced, with this book I have seen a light that makes me want to try to do whatever I can during the short remainder of my life. I want to live the rest of my life to its fullest!

Tokiji Suzuki, "On the Publication of the Collection", Tokuji Suzuki’s collection of paintings: Proof of Life – From a Hansen’s Disease Sanatorium, (Koseisha, 2002).