Molokai, Hawaii (USA)

Europeans began recording leprosy in Hawaii early in the nineteenth century. The parliament introduced a bill to prohibit its spread on January 3, 1865. The legislation requiring life-time involuntary isolation continued until 1969. People with leprosy were only treated as outpatients after 1974.

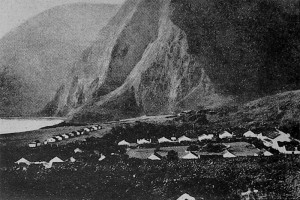

Land on the island of Molokai was set aside for the first contingent of people who arrived on January 6, 1866.

YouTube video

Gene Colling: Kalaupapa, Molokai, A Story to Tell

By 1905, 5,800 people had been isolated at Kalaupapa, on Molokai.

The history of leprosy in Hawaii should be understood in the context of the fraught climate of Hawaiian politics, the plantation economy, and the strategic value of Hawaii’s location in the Pacific to the US relations with China. (Gussow)

Scholarly Essay:

R D K Herman, “Out of Sight, Out of Mind, Out of Power: Leprosy, Race, and Colonization in Hawai’i”

Abstract:

Leprosy policies in late 19th-century Hawai‘i reflect and embody the mobilization of racial discourses to disempower Hawaiians. These discourses began with early missionary assessments of the causes for disease and depopulation among Hawaiians, but they became more focused as White commercial interests needed control of land and power for the booming plantation industry. The isolation of “lepers” to Kalaupapa peninsula occurred at the same time that White business interests were steadily taking over the Hawaiian government, culminating in the overthrow of Queen Lili‘uokalani in 1893. An analysis of historical materials concerning leprosy during this time reveals the intertwining of leprosy policies and colonization.

Key Person:

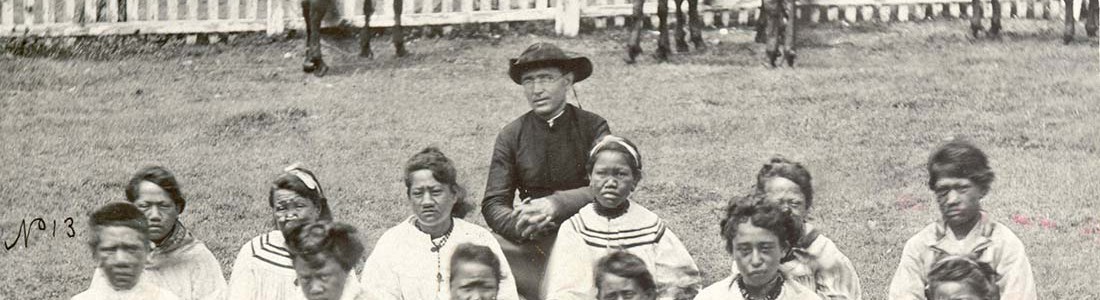

Joseph de Veuster or Father Damien, the Belgian priest, born in 1840 at Tremeloo, near Mechlin, volunteered to go to Kalawao, Molokai, in May 1873. He found more than eight hundred people living in the settlement in the most rudimentary and dispiriting conditions. He worked tirelessly to improve the colony, to provide adequate shelter for the people, and to represent their needs to the parsimonious Board of Health.*2

But within three years, he had contracted leprosy, which he announced in a sermon when he addressed his congregation as “we lepers”. He died on April 15, 1889, after spending sixteen years in the settlement. His death seemed to indicate conclusively that leprosy, as a germ disease, was communicable. (British Medical Journal)

Sources

*1 Reverend Mr Stewart noticed the presence of the disease in Hawaii in 1823. On May 22, 1823, Reverend Charles C. Stewart wrote, “The inhabitants generally are subject to many disorders of the skin; the majority are more or less disfigured by eruptions and sores ….”

The steep cliffs overlooking the settlement

Mouritz noted leprosy in 1830. A A St Mouritz, “The Path of the Destroyer”: A History of Leprosy in the Hawaiian Islands and Thirty Years Research into the Means by which it has been spread (Honolulu: Honolulu Star-Bulletin, 1916), p. 30

Hillebrand observed it amongst the Chinese population of Hawaii in 1848. Dr W Hillebrand, Surgeon to the Queen’s Hospital, quoted in Ralph S Kuykendall, The Hawaiian Kingdom, 1854-1874 (Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 1953), p. 73

*2 Father Yzendoorn, Ira Dutton, and visitors to the colony such as Jack London and Robert Louis Stevenson also reveal a glimpse of the man behind the legend.

Baldwin Home for Boys

(Kalawao, Molokai, 1921 Foundation Raoul Follereau Archives)

“A Victim of Leprosy” British Medical Journal (26 January 1889): 222

Ron Amundson and Akira Oakaokalani Ruddle-Miyamoto, “A Wholesome Horror: The Stigmas of Leprosy in 19th Century Hawaii” 3.4 30(2010) Disability Studies Quarterly: the First Journal in the Field of Disability Studies

Greene, Linda W. Exile in Paradise: The Isolation of Hawai’i’s Leprosy Victims and Development of Kalaupapa Settlement, 1865 to the Present. Washington, D.C.: US Department of the Interior, National Park Service, 1985.

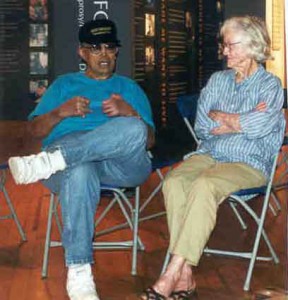

Bill Malo – sent as a child to Molokai

Zachary Gussow, Leprosy, Racism and Public Health: Social Policy in Chronic Disease Control (Boulder, San Francisco & London: Westview Press, 1989): 85-107.

Pennie Moblo, “Blessed Damien of Moloka’i: The Critical Analysis of Contemporary Myth” Ethnohistory 44.4 (1997): 691-726.

DOI: 10.2307/482885

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/482885