Aspects of the Collection

The archives in the ILA Global Project on the History of Leprosy provide users with a key to collections from all over the world. Each archival entry contains a description of a collection so that if you are searching for primary sources to do with the history of the work against this disease, you can find out where those sources may be held and who to contact so that you can make arrangements for viewing them.

This project does not hold all of these records in one place for two reasons: firstly, there are too many, and secondly, they belong in their context, as close to where they were created as possible.

This latter reason is terribly important because the history of this disease is so closely tied to place.

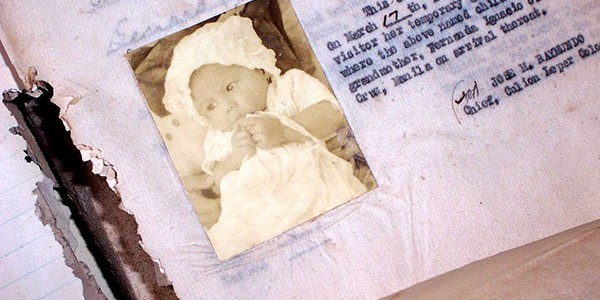

When people were taken from their homes and isolated in far flung places, their medical records were created where they were. This often included photographs of the person and some details about where they were from and their age on admission. The descendants of those people, if not the actual people who were isolated, have often grown up in the same isolated old colonies. Sometimes the children were taken away from their parents and when they return to try to trace their families, the remaining medical records are sometimes the only clue that they have to re-establishing their family connections.

Needless to say there is much more than medical records in the archives that we have identified. To feature one remarkable collection:

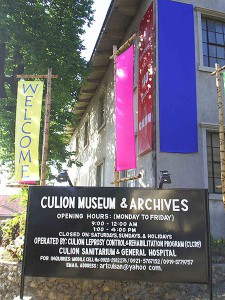

Featured Collection: The Culion Museum and Archives, the Philippines

The Museum on Culion

The Culion Museum contains valuable information with regards to the establishment of the Culion Leper Colony in 1906. It documents the discriminatory legislation enforcing compulsory segregation in Culion and the research and clinical trials carried out using chaulmoogra oil and its esters within the colony. The resultant effects on colony life are recorded in relation to the community interaction of patients, the segregation of children of leprous parents, the use of special currency, the results of different research on childhood leprosy and other pioneering research on bacteriology, pathology and epidemiology of leprosy. It possesses old apparatus and instruments from the earliest years of the colony. It also has lists of the patients sent to Culion from different parts of the Philippines.

Culion is the original site of the Leonard Wood Memorial before it was transferred to its present location in Cebu. There is a rich library of materials on leprosy compiled by Damien Dutton Recipient and first Editor-in Chief of the International Journal of Leprosy, Dr Windsor Wade. Until April 2007, the precious and unique archive on Culion was in danger of disintegrating from exposure to heat, sunlight, and sea air, until the support provided by the Sasakawa Memorial Foundation made it possible for Dr Cunanan, the chief of leprosy control on Culion, with the expertise of Museum archivist, Ricky Punzalan, conservator, Alex Botelho, and Artistic Director, Mimi Santos, with the labour of those on Culion, to refurbish and redesign the Museum and rehouse the collection.

Many of the publications held here are extremely difficult to access elsewhere. To have them gathered together in one site is to permit a researcher interested in the history of leprosy a rare opportunity to access a library of resources that it would be heartbreaking to allow to perish.

The earliest issues of Danielssen and Boeck ’s publications, Leprosy Notes (from the inception of the British Empire Relief Association), the International Journal of Leprosy, Leper Quarterly: Chinese Mission to Lepers (from 1928), and Jeanselme’s La Lèpre (1934) are all extremely difficult to come by anywhere, much less together in the same location.

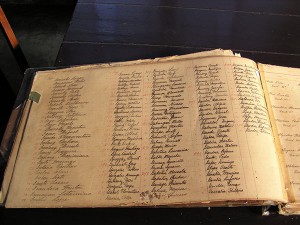

In addition, but not secondary, the actual records of Culion as a sanitarium, established in 1906 are utterly unique to this place. As such, they provide a record of the leprosarium from its inception until the present, its admissions, visitors, residents, medical activities, staff activities, and research.

Most poignantly, they provide a unique record of the lives of people, most especially the human faces, through the photographs, taken as part of the case history, of those affected by leprosy and the subjects of the policies for control of the disease. These are part of the heritage of Culion and the Philippine people. People wanting to trace family members who “disappeared” would be able to piece together parts of their history from what is held at the Culion Museum.

The published and unpublished documents at Culion have to be seen not only within the historical context of the island, but also within the worldwide context of modern leprosy work that now spans more than two centuries. The Museum should also be considered within the context of other museums dedicated to the history of leprosy, the Leprosy Museum at Bergen being the prime example, but including the Acworth Museum in Mumbai, India and the one to be established at the National Resource Centre for STI/ Leprosy Control and Prevention, in Nanjing. These should be viewed as evidence of both the profound effect of leprosy as a disease, and an extraordinary chronicle of effort and persistence on the part of those involved in its control and treatment.

These records simply represent the “tip of the iceberg” of important unpublished documents at Culion. In addition, there are important collections of published records and also a unique collection of photographs, medical and laboratory records. But the following were the most vulnerable and most urgently in need of attention:

Register of Visitors: “Philippine Health Service: Culion Leper Colony Register of Visitors”

The registers at Culion

This register, from 1928 until 1991, records the date of arrival, name, official title, home address and remarks of those who have visited Culion. It provides a fascinating tableau of passers by. Many came as officials or dignitaries, many as medical people who were working against leprosy in other parts of the world and for whom Culion was an authority and a model. Many others came as missionaries or members of the American navy or armed forces, some simply came out of curiosity. All have signed the register of visitors and made comments.

Eight Record Books titled “List of Released Patients from Culion Leper Colony (Discharged, paroled or released as non-lepers)”.

The registers at Culion

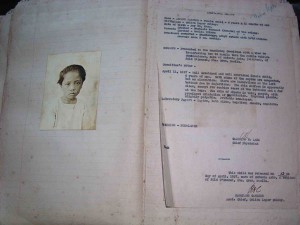

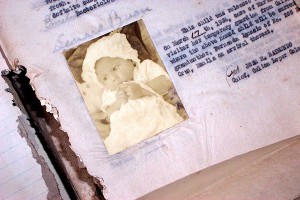

These books contain individual records, mostly of non-leprous children, but also of adults. They usually all have a photograph of the child on the left-hand side of the page and a typewritten summary of the case on the right. The photograph of the child is accompanied by an individual record of name, birthplace, date of birth, names of parents who are inmates of the colony, details of presentation to the examining committee with their notes, the lab report, and the decision for release: “non-leper”. The records are for 1924, 1924-1925 (197 in number), two for 1925-6, two for 1927, 1929-33, 1933-6 (190 in number).

the case files at Culion

Pasted under the case summary are two other pages: a release form and an adoption paper. Through the release document, the child is surrendered by the mother and father to a member of the family, friend, or to adopting parents outside Culion. This is done under condition that they will assume the duties of guardian to the child. This includes care, protection, support and education. The form is signed before the Assistant Chief Culion Leper Colony Ex-Officio Justice of the Peace and Notary for the Culion Reservation.

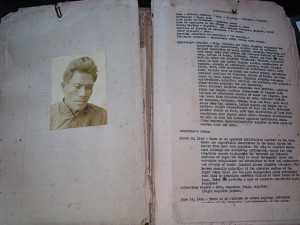

the case files at Culion

In the same books are individual records of adults who were discharged as “smear negative.” These reports include photographs of the face, name, birthplace, last place of residence, date of admission to the colony, family history, duration of leprosy on admission, physical condition on admission, treatment received, physicians’ remarks, committee’s notes tabulating the negative period with a decision for release. Typical is the remark “eligible for parole, he having completed the required six months negative.” The documents are signed by “Casimiro Lara, Chief Physician”. Once again, the photographs and details give human faces to people whose lives have been affected by the disease.