Kenya

Main hospital building Chogoria Sep1926

Anti-leprosy workers from BELRA were confident that they had identified practically all the known cases of leprosy in the eastern districts of Teso, Lango, and Mbale, Kenya. At the time, there were four leprosy settlements in Kenya and it seemed that that not many people had been infected with the disease. (Rogers) Then in 1927, a survey of 128,147 people, on the shores of Lake Victoria, revealed 461 leprosy cases, or 3.6 per mille. In 1928, Robert Cochrane stated that while there was no reliable estimates, both the Government and Mission doctors agreed that in the presence of the disease was high in certain districts, especially amongst the Thanaka people who inhabited the lower slopes of Mt Kenya. People with leprosy also attended the Government infectious Disease Hospitals at Nairobi, Mombasa, or the six leprosy camps. (Cochrane)

On his tour of East Africa, Frank Oldrieve was impressed with the mission hospital run by the Church Missionary Society (CMS) at Maseno, in Kenya, 20 miles from Kisumu, on Lake Victoria, Nyanza. There was an outpatient department. In addition, there were plans for a government leprosy village, or settlement, next to the Mission so that the CMS Doctors could take charge of the institution. The Church of Scotland were also working at Tumutumu [Tumu Tumu] at the base of Mount Kenya. (Oldrieve, Secretary’s Report)

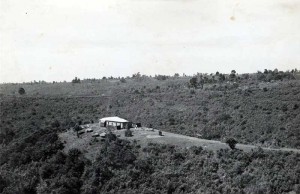

Leprosarium Chogoria 1936

Oldrieve recommendations included opening a Kenyan Branch of the British Empire Leprosy Relief Association (BELRA); establishing a new colony near Mombasa made of small huts, rather than large buildings, so that people could live ordinary village lives as much as possible, in the place of the colony at Malindi; establishing a village at Maseno, near the CMS hospital, and transferring the work at Kakamega to there; making the latest treatment available at all the hospitals; giving special attention to healthy children; and embarking on educational campaigns. (Oldrieve, Memorandum)

In 1928, BELRA aimed to provide treatment centres for leprosy at every hospital or medical centre in Kenya where a suitably qualified person was able to carry out the work. They claimed that 547 people had admitted themselves to leprosy institutions, seeking Alepol treatment. (Rogers)

Twenty years later, Dr. Ross Innes estimated the total number of leprosy cases in Kenya to be 35,000, but most were non-infectious and could be treated at home. Preliminary plans for a leprosarium at Itesio were made for about 500 infective cases.

Prior to 1949, the Kenya annual medical reports indicated that anti-leprosy measures did not change very much. However, with the introduction of the sulphones, combined with the stimulus of Ross Innes’s surveys in revealing the serious incidence of leprosy in the Kenya Protectorate, the Government was prompted to try to control and possibly even eradicate the disease, provided the necessary finance was available.

Ross Innes found only 50-60 people receiving effective treatment and some 200 others in two camps. The incidence in different areas varied from 0.9 to 32.7 per mille. In 1950, in Kenya, good results from the use of sulphones were reported within 17 months for the non-infective and mild tuberculoid and early “indeterminate” cases. Infective lepromatous cases also showed great improvement. The report for this year added that “There now seems to be little doubt that leprosy can be controlled, and possibly even eradicated, provided the necessary finance can be made available.” Three leprosaria were required, each under a full-time medical officer. (Rogers) By 1953 the new leprosy camp at Itesio already had 2,500 registered patients, most of whom were out-patients coming from as far as 15 miles away for treatment.”

Sources

Leonard Rogers, “Leprosy Incidence and Control in East Africa, 1924-1952 and the Outlook” Leprosy Review, 25.1 (1954): 41-59.

Robert Cochrane, Leprosy in Europe. The Middle East and near East and Africa, London: World Dominion Press, 1928, p 30.

Frank Oldrieve, British Empire Leprosy Relief Association, Secretary’s Report No 5, “Report on Tour in Kenya Colony and Protectorate”, 1927.

Frank Oldrieve, “Memorandum on Leprosy Work in Kenya Colony and Protectorate”.