Myanmar (Burma)

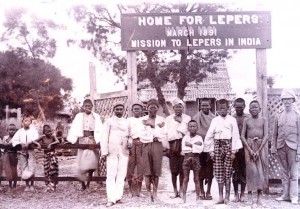

Patients at the first home built by The Leprosy Mission in Mandalay, Burma. 1891

Burma was one of the earliest countries in which WHO collaboration took place. The country had long been recognised as having a problem with leprosy. In the nineteenth century, the Leprosy Commission (1890-1891) had visited and concluded that 8.6 out of 10,000 people had the disease in the whole country, but in Central Myanmar, it was closer to 14.4 /10,000. In 1932, the census established that there were 11,127 people with the disease — around 7.6/10,000. Three years later, Dr Isaac Santra reported 250 cases per 10,000 in the Mandalay area. (Leprosy Review) There were six leprosy homes that could accommodate 1,650 patients, four isolation centres and some voluntary segregation camps. The Central Leprosy Clinic was in Rangoon. Each leprosy home also had an out-patient clinic. Very few of the general hospitals and dispensaries in Burma offered treatment for leprosy, although some in the Shan States were beginning to treat leprosy-affected people as out-patients.

WHO involvement in leprosy in Burma came about as a result of a request from the Government of Burma for a short-term consultant to help survey and reorganise anti-leprosy work. WHO agreed to make a consultant available for three months and from August 22 to November 21 in 1951, Dr Dharmendra from India, who was at that time at the Calcutta School of Tropical Medicine, received a mandate, agreed between the Government of Burma and WHO, to survey the country and advise and assist the government in expanding anti-leprosy work. He was also required to establish a colony or sanatorium for leprosy-affected people in a rural area as a government-sponsored project and also a Central Leprosy Institute and Clinic in Rangoon.

Anti-leprosy work in Burma was handicapped by a shortage of trained medical personnel, a situation that had been exacerbated by the considerable impact of World War II on the country. Armed with the promising sulphones and a heightened awareness of the role played by lepromatous leprosy in the spread of the disease, Dharmendra was able to assess the situation with a degree of confidence. He visited as many leprosy homes and isolation centres and clinics as he could. He surveyed the refugee camps, the schools, and the prisons, He sought out locations where leprosy was not supposed to be a serious problem. He talked to and also educated members of the medical profession and the general public, on the most recent information about leprosy. He tried to persuade people to support local efforts against the disease. Finally, he reviewed the existing legislation and recommended how work should develop in the future. (2)

Together with Dr Tha Saing, the Special Leprosy Officer for Burma, and Dr Sao Naw Kham, the Chief Medical Officer of the State, they visited the Shan States and met civil surgeons, health officers, and deputy commissioners of the districts. He also enlisted the cooperation of elders and influential public men, including the Saobaws or chiefs in the Shan states. (3)

From his observations, he concluded that the prevalence rate of leprosy in Burma, as a whole, was 0.5% which meant about 100,000 cases of leprosy in the country and of these about 50% were lepromatous. Twenty percent were children, of whom 30% were lepromatous. No part of the country was free of the disease. He suggested that it may have been significant that the Shan Plateau, where the prevalence and the proportion of lepromatous cases was highest, was closest to parts of China and Thailand where the disease was also endemic. He found that the existing activities against the disease were grossly inadequate. (52)

His recommendations can be seen to be driven by a desire to produce cooperation across all strata of society, but especially by mobilising the influential people in the country, such as the officials, professionals, Buddhist priests, and village elders. He did not wish to extend the asylum system, but he did see a place for agricultural colonies where people could live self-sufficient lives with their families in relative isolation. In addition, he still considered that openly infectious cases be isolated at least until they were bacteriologically negative.

For the official story of leprosy control in Burma (now Myanmar), see Kyaw Lwin, Tin Myint, Mg Mg Gyi, Mya Thein, Tin Shwe, and Kyaw Nyunt Sein, “Leprosy Control in Myanmar 1952-2003 – a Success Story” Leprosy Review 76 (2005): 77-86.

Sources

Kyaw lwin, Tin Myint, Mg Mg Gyi, My A Thein, Tin Shwe, and Kyaw Nyunt Sein, “Leprosy Control in Myanmar 1952-2003 – a Success Story,” Leprosy Review 76 (2005): 77.

Dharmendra, Burma Short Term Consultant Report, WHO 1951