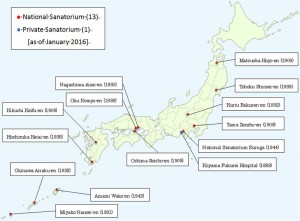

Nagashima (Japan)

Map of leprosaria in Japan

The Public Health Bureau of the Japanese Ministry of the Interior in October 1930 formulated a long-term plan with several stages to deal with 15,000 people with what was characterised as advanced leprosy in Japan. While there was accommodation for 5,000 people with leprosy, the new eradication plan aimed to isolate everyone with leprosy in leprosaria, no matter what their status. Even those who had the means to remain at home were represented as “socially outcast and miserable, inaccessible to medical treatment and a danger to their families.” The administrators expected that with complete isolation, within ten years leprosy would come under control, and within twenty years it would be eradicated. (112) They planned to provide accommodation for an additional 500 people, every year, for twenty years. The budget per person for building and annual expenses was calculated on a fifty-year plan. IJL 1.1(1934)

Receiving Station, Nagashima Aiseien

Dr. Kensuke Mitsuda planned with the Government to establish a network of leprosaria. By 1940, the plan was almost completed, with five designated national leprosaria to house 9,125 people. In 1941, five additional local leprosaria were transferred to the supervision of the Central Government, and then in 1943 and 1944, two more national leprosaria were established so that by 1945, there were thirteen national leprosaria.

By the end of 1930, the National Leprosarium was founded. Its first director was Kensuke Mitsuda. Early in the following year, it was named the National Leprosarium Nagashima Aiseien, by the Interior Ministry, and 85 patients were transferred from Tama Zenshoen Sanatorium, Tokyo. In 1932 there were 452 people at Aisei-En (National Leprosarium Nagashima).

Nagashima leprosarium (1931)

This summary records the visits of outside experts who were focussed on anti-leprosy care and control in order to demonstrate the favourable reception that Japanese measures were afforded by the international community. The point is to argue that the Japanese administrators were encouraged by outsiders, not censured in their policies. This is not to take away responsibility for what happened in Japan but to place the Japanese policies in their international context.

On his visit to Nagashima, A. Oltmans, the District Secretary of the American Leprosy Mission, reported very favourably to Etienne Burnet of the League of Nations Health Commission:

Patients’ dormitories — women’s area in foreground (1931)

“The new National Hospital on Nagashima — “Ai-sei-en” under the direction of Dr Mitsuda gave me great delight. I spent three days on the Island as the guest of the Hospital and several features of the situation made such a lively impression upon me that I have made arrangements with the Japan Times to prepare an illustrated article on the subject.”

“The most noted feature I observed at Nagashima is the voluntary entrance of all the patients – now 461 – with the exception of 81 whom Dr Mitsuda took with him from the ‘Zensei Byo-in’, his former charge.”

Source: Correspondence from A Oltmans District Secretary, the American Mission to Lepers, to Etienne Burnett, Secretary League of Nations Leprosy Commission. November 18, 1931

Nagashima leprosarium (1931)

Dr Isaac Santra, an Indian doctor, visited in 1934 and reported in Leprosy in India. He described “Ai-Sei-En” as being situated on a beautiful island where the sunrise was famous. He noted that it had been opened for three years, and the Japanese Government had spent 1,200,000 Yen to build and equip it. When he visited it accommodated 780 people. He was very impressed with Dr Mitsuda which he described as combining “the qualities of an educationalist, social worker, and doctor – a living encyclopaedia on matters concerning leprosy.” (26)

His remarks about the staff are illuminating:

Administration building, Nagashima leprosarium (1931)

The doctors and nurses work for about 10 hours daily. On seeing no games or other recreation I asked what were their recreations. The reply was “Enjoyment is a bad word in Japanese. The spirit of this asylum is to find enjoyment in serving the patients”. It is wonderful how with such heavy work the members of staff always laugh. They do not walk but run. Everybody seems to be busy with something, everybody seems to be working with a purpose.

When people were admitted, they were isolated and examined and treated for any other diseases they may have had. Once they were free from other diseases, they were admitted to the colony. Everything they brought with them was sterilised. There were poultry, pigs, and cows, and an orchard and gardens for the patients.

Santra remarked that “The patients are well behaved, always active, disciplined, and give credit to the Japanese.” (26) He noted too everyone who died was autopsied. As a result, there was a vast collection of material that was frozen. Married male patients were “on their own consent sterilised by vasectomy.” (He describes the procedure which he remarks is a simple one) (27) People were treated with hydnocarpus oil, injected under the skin, with up to 240 injections in one year.