Living the Work Camp Life

Originally published in the WHO Goodwill Ambassador’s Newsletter for the Elimination of Leprosy, Issue No. 27 (August 2007). The information was correct and current at the time of publication.

Ryotaro Harada’s calling is organizing work camps in leprosy-affected villages in China.

In my third year at university, when I should have been job-hunting, I joined Korean and Japanese volunteers at a work camp at a Chinese leprosy village. It was February 2002.

As a boy I had been bullied at school, and determined to become a journalist so that I could tackle the issue of discrimination. I thought the work camp experience would be a useful talking point at job interviews.

At the same time, I was beginning to wonder if I really understood what discrimination meant. Maybe I was guilty of it, too. With these thoughts in mind, I decided to take part in the camp, because I knew that people affected by leprosy were among the most discriminated against of all.

Yankeng village in Guangdong was established in 1957. At the time, about 300-400 people diagnosed with leprosy were forcibly isolated there. To get to the village we drove for miles along a dirt track through the mountains. On arrival, volunteers who had been there before got out and shook hands with the villagers, some of whom appeared to have no fingers. When I alighted, saying “Hello” was all I could manage to do. I felt it would have been insincere of me to shake hands.

After dinner that evening, I had a ‘conversation’ with one of the villagers, Mr. Ou. Over 15 minutes of written exchanges using Chinese characters, it seemed like we were communicating surprisingly well. In truth, however, I was concerned, because I was touching his ballpoint pen and notebook. With a gesture, he invited me to his house. I grew more nervous.

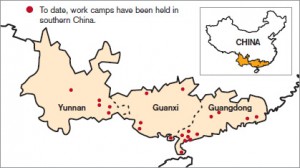

JIA Activity Map

Inside, the air was chilly, and slightly damp. Now I was scared. Although I knew that I wouldn’t catch leprosy, I was still afraid to breathe in the air in the room. I hesitated to sit down. When he handed me a monkey banana, I didn’t know what to do. I couldn’t refuse it, so I just stuffed it in my mouth and swallowed

Mr. Ou showed me a photo. It was taken during an international leprosy conference on an outing to the Great Wall. He also showed me a postcard from a Japanese friend. He looked so pleased, and I realized he was just a normal person. Indeed, he might have been my grandfather. As he was telling me about the photo, I sat down. I began breathing normally and even laughed. When it was time to leave, Mr. Ou saw me to my accommodation. “See you again tomorrow,” I wrote, and held out my hand.

Grandma Lin lived a couple of doors down from where the work volunteers stayed. Her fingers were stumps, and her left leg was made of tin. Every morning when I left my room, Grandma Lin would be sitting in front of her door on a wooden chair.

“Morning!” I would call out. Grandma Lin couldn’t talk, but would flash me a smile. Is this the smile of someone who has been oppressed for long years, I thought? I held her in great respect.

RETURN TO CHINA

In June 2002, I became involved in preparations for another work camp in Linghou village in Guangdong, and went there in September to conduct a survey. Compared to Yangkeng, living conditions were much worse, and people had glum expressions. Back home, my job-hunting had not been going well, and as I looked around Linghou, I became increasingly depressed. I didn’t want to have to come back for the work camp in November, as I promised I would.

But I did, and through the experience I came to know the villagers better and appreciate what work camps could achieve. This was also the first work camp in which Chinese students participated, although they didn’t stay at the camp overnight.

In April 2003, immediately after graduating, I went to live in Linghou. From there I traveled around persuading local students to get involved. Up to that point, the volunteers had mostly come from overseas, but from August, Chinese students became full and enthusiastic participants in work camp activities.

Since then, the work camp program has expanded rapidly, leading to the establishment of JIA . Work Camp Coordination Center to put the program on a solid footing organization and build a global network (see Partners).

BUILDING BONDS

Harada with Linghou villager Cai Wanquing

Work camps are all about creating bonds between people . between villagers and volunteers, between volunteers themselves, and between villagers and neighboring communities.

I tell potential recruits not to approach a work camp with the idea of “ending discrimination against people affected by leprosy,” “offering a hand of love to the suffering” or “participating as a volunteer.” Instead, they should ask fundamental questions, such as “what is leprosy,” “what is love?” and “what is being a volunteer?” Their answers are likely to be, “I don’t really know, but I’d like to find out.” That is the first step.

Volunteers arrive, picturing the degree to which the villagers must be suffering. Some of them are fearful when they see what the disease has done to hands and feet. However, the most frequent impression they have is: “The villagers have a far more positive outlook than we imagined; they’ve accepted the fact of leprosy and are getting on with their lives.”

Residents of Teng-Qiao village in Guangdong Province bid farewell to volunteers at the end of a JIA work camp.

This in turn causes volunteers to reflect on their own lives, and see their day-to-day concerns in a fresh light. Little by little, bonds develop between the villagers and the volunteers, and they become like family. (Indeed, that is what “jia” means in Chinese.) When the work camp comes to an end, the volunteers return home, revitalized.

As for the villagers, the benefits of the work camps go beyond paved roads and new toilets. Isolated, abandoned and disdained for long years, they have an opportunity to interact with people who take a straightforward and genuine interest in them. The results are heartwarming on both sides.

In addition, seeing the student volunteers mix easily with the villagers sends a message to people living nearby. In Pingshan village, where many camps have been held since February 2004, there is today almost no discrimination toward villagers in surrounding communities.

Pingshan has also hosted a reunion between one of the villagers, Uncle Tao, and his cousin, who were reunited after 53 years through the efforts of volunteers. In the second half of July, Uncle Tao made a successful visit to his hometown in the company of volunteers. Such home visits are being organized at other villages too.

On a personal note, I married Cai Jieshan, a Chinese volunteer, in October 2005. In the days before Chinese volunteers became regular participants in the camps, Jieshan often came to visit Linghou, and soon the villagers were asking, “When are you two getting married?” One villager more than most eagerly anticipated the announcement. Her name was Cai Wanqing. On October 11, 2005, the day after we registered our marriage, I went to Linghou with the happy news. But when I told Cai Wanqing, she just said, “Oh, I see.” It was as if all the enthusiasm had drained from her. A couple of weeks later, she was dead. I was told that her last words were, “I’ll never see Ryotaro and Jieshan again.”

JIA work camps are putting down roots and over time I hope to see them spread to other parts of the world. At first, I think the focus should be on leprosy, but there is no reason why they should not eventually concentrate on helping other disadvantaged communities. JIA’s motto is “World as One Family by Work Camp.” It may be a dream, but it is one I hope to see realized in my lifetime.

AUTHOR: Ryotaro Harada

AUTHOR: Ryotaro Harada

Ryotaro Harada is General Manager of JIA . Work Camp Coordination Center, an NGO based in China.

Leprosy FACTS

The global registered prevalence of leprosy at the beginning of 2007 was 224,717 cases; the number of new cases detected during 2006 was 259,017. Four countries (Brazil, DR Congo, Mozambique and Nepal) have yet to eliminate leprosy as a public health problem. Together they accounted for about 23% of all new cases detected in 2006 and 34% of all cases registered at the beginning of 2007. (Source: WHO)