Poetry from the Heart

Originally published in the WHO Goodwill Ambassador’s Newsletter for the Elimination of Leprosy, Issue No. 12 (February 2005). The information was correct and current at the time of publication.

After being diagnosed with leprosy, Tetsuo Sakurai was forced to leave home at the age of 15. He didn’t return for more than 60 years.

Tetsuo Sakurai was born Toshizo Nagamine in 1924 in Myodo-zaki, a small village in Tsugaru in the far north of Japan’s main island of Honshu. Toshizo was the seventh son in a wealthy family that owned large apple orchards, and his early life was a comfortable one. A sensitive boy with a good sense of humor, Toshizo entered elementary school in 1931 and was popular with his fellow students.

At 13, he exhibited the first symptoms of leprosy. Two years later, when he was studying for middle school entrance examinations, he was suddenly told by his father that he would have to give up his studies. At that point, he realized he would be leaving home and that life was about to take an altogether different course.

At first, he received treatment in neighboring Hirosaki for 10 months but after he showed no improvement, his parents were obliged to have him quarantined in a sanatorium under Japan’s 1907 Leprosy Prevention Law (not repealed until 1996).

They saw him off from Hirosaki Station as he departed for the town of Kusatsu, carrying apples, rice balls and dried squid wrapped in a cloth on his back. Although he felt utterly desolate, Toshizo did not want to upset his parents by crying in front of them over the enforced separation.

In 1941 Toshizo entered Kuryu Rakusenen, one of 13 sanatoria established by the Japanese government between 1909 and 1945, and was given the new name, Tetsuo Sakurai.

Although called a sanatorium, those with mild symptoms were put to work on nearby farms, forced to do hard labor and nurse seriously sick patients. Despairing of their future, many patients took their own lives. Any attempting to escape were placed in solitary confinement as a warning to others.

To cope with this harsh life, Tetsuo decided to devote himself to study and purchased a collection of Japanese literary classics. He was befriended by the educated daughter of a wealthy Kyoto restaurant owner who become Tetsuo’s mentor. Under this erudite teacher, he began studying topics such as theology, European philosophy, Buddhism and literature at the age of 19.

At 21, he “married” a young woman named Masako. This marriage had no legal basis, but was recognized within the sanatorium. In those days, before they entered into such a union, male leprosy patients had to be sterilized. The procedure was not properly performed on Tetsuo, however. When Masako unexpectedly became pregnant, she was forced to have her baby aborted.

Two years later, Masako died of leukemia. The following year, Tetsuo came down with high fever. By the age of 29, he lost his sight, all his fingers and the use of his vocal cords.

It would be many years before Tetsuo adjusted to his condition. Eventually, he joined a group for the blind and developed a passion for Japanese chess. Then, at the recommendation of Shigenobu Kobayashi, the sanatorium’s director, Tetsuo joined the poetry group. Listening to poetry turned him back onto to literature, and at the age of 57, he composed his first poem, whispered to a member of staff who wrote it down for him. He also began reading the Bible, and was baptized as a Catholic at the age of 60.

In 1988, Tsugaru Lullaby, his first collection of poetry, was published. Two more volumes have followed.

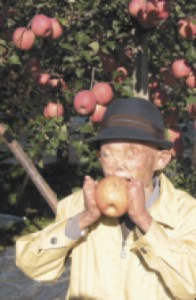

Tetsuo finally returned to his Tsugaru homeland in October 2001 at the invitation of his family. He spent only a few days there, but it was a time of great joy for him. A TV documentary about Tetsuo’s return to Tsugaru after 60 years was broadcast by Japan National Broadcasting Corp. in 2002, generating a huge viewer response.

Tetsuo Sakurai pictured at the family orchard in Tsugaru in 2001.

Solitary Musings

On a spring evening in the ward, I press two seashells against my ears, and, closing my eyes, hear the roar of the waves in faraway Tsugaru, as we heard them then, standing shoulder to shoulder, atop the dunes of Tsugaru in the spring of my seventeenth year. And I hear the caw of the gulls that skim the waves, as, left alone to solitary musings on this early evening in spring, I feel my heart pounding.

(Translated by Charles De Wolf)