Europe

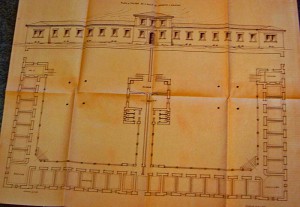

Plans for a leprosarium, Greece

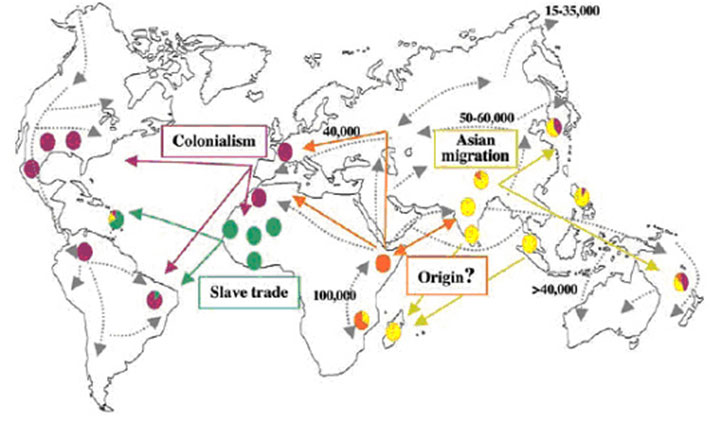

The most recent theory is that leprosy came to Europe from both West and East Africa and then also from Central Asia and the Middle East. Scientists argue that the history of leprosy in Europe was dominated by a drawn-out leprosy epidemic that may have lasted a millennium and peaked between the 11th and 14th centuries. (Mendum et al. p.4)

The early presence of leprosy in England is established from the archaeology of skeletons from the 4th century AD. These were excavated from a Romano-British cemetery, at Poundbury Camp in Dorchester, between 1966 and 1973. (Reader) Two skeletons from 10th to 12th century burials at the leprosy hospital of St Mary Magdalen, near Winchester in England, show very little difference between the ancient and the modern DNA strains of M leprae. (Mendum)

Doctor, priest, and inmates at Spinalonga, 1931

When Vilhelm Møller-Christensen systematically excavated the Naestved St George’s Hospital (1250-1550 AD), he established the presence of leprosy in medieval Denmark. Among the 155 remains that showed clear signs of the disease, he discovered well-preserved skeletal remains from the late thirteenth century of a 25-30 year old male of status.

Further evidence of leprosy’s widespread European presence also comes from two skeletons from a cemetery at Žatec in north-western Bohemia (Czech Republic). These had been buried either before the second decade of the 12th century or even in the second half of 11th century. The researchers argue that this find rules out the possibility of the disease arriving from the returning Crusaders, for a Bohemian contingent under Prince Vladislav II participated in the Crusades from 1141 to 1142.” (Likovský at al.)

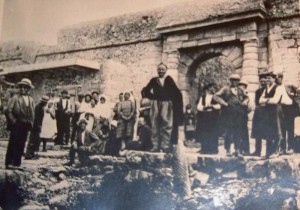

Patients near the entry to Spinalonga

Leprosy began to decline in Europe between the 14th and 16th centuries, perhaps as a result of the Black Death and the rise of tuberculosis. (Mendum) The “disappearance” of leprosy from medieval Europe needs to be considered against the evidence of traces of the disease in Europe over the next three hundred years, in addition to the growing presence of leprosy in the New World. In the sixteenth century, both the Spanish and the Portuguese were aware of the need to make some provisions for leprosy in their colonial possessions, as well as at home.

In the nineteenth century, the medieval strictures against leprosy were used to argue for the success of isolation measures as a means of leprosy control. (Mercier, Newman). The reason why leprosy seemed to disappear in Europe is still unclear, so the efficacy of isolation as a control measure is unproven. (Creighton, Gussow). Rawcliffe argues that the medieval lazarettes offered a monastic refuge for the leprosy affected, in keeping with what was considered an acceptable and praiseworthy way of life.

Spinalonga, Crete, 1931

Norway experienced an endemic of leprosy in the early nineteenth century. In 1816 Johan Ernst Welhaven (1775-1828) exposed the shameful living conditions at four hundred year old St Jørgen’s Hospital for lepers in Bergen, Norway, as a “graveyard for the living” and twenty years later, the Bergen community petitioned parliament to build new nursing homes for the leprosy affected. A Royal Commission was established and Dr Jens Johan Hjørth (1798 – 1873), who surveyed leprosy in Norway in 1832 and traveled abroad to research the treatment of cutaneous diseases, made recommendations to the government for stemming the progress of leprosy.

Jarvso leprosarium, Sweden, was built in 1870.

Subsequently, leprosy control in Norway focused on a system of medical registration, legislation, hospitalisation, and research. Surveys were conducted in 1836, 1845, and 1852, and a medical superintendent for leprosy, Ove Guldberg Høegh (1814 – 1863), was appointed to be responsible for a national leprosy register, established in 1856. St Jørgen’s Hospital and three additional hospitals, as well as a research hospital, were dedicated to leprosy, and the modern knowledge of leprosy entered a new era through the work of Daniel Cornelius Danielssen (1815-1894), Carl Wilhelm Boëck (1808-1875) and Gerhard Henrik Armauer Hansen (1841-1912).

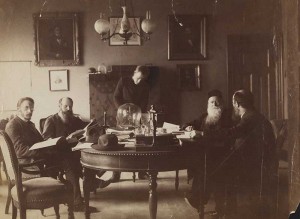

Part of the science faculty at the Bergen Museum, including Gerhard Armauer Hansen (second from left) and Daniel Cornelius Danielssen (second from right). Via Wikimedia Commons.

Danielssen and Boëck produced what Ruldolf Virchow described as the beginning of biologic knowledge in leprosy. Their most notable publication was Om Spedalskhed (Christiania 1847), which was translated into French as Traité de la Spedalskhed ou Elephanthiasis des Grecs (Paris 1848), and the Atlas Colorié de Spedalskhed (Elephantiases des Grecs), which contained 24 lithographs by J L Losting (1810-1876). The cause of leprosy was attributed to an inheritable dyscrasia of the blood, capable of latency, but emerging in unfavourable living conditions. They argued against contagion saying that they had not observed a single instance of spread by contagion in their vast experience at St Jørgens. They subsequently argued that if the disease was in fact carried in a latent state by individuals, they should be stopped from reproducing. This mandated sexual segregation, and in 1850, the medical committee recommended that the marriage of leprosy- affected people and their children and grandchildren be prohibited.

Gerhard Henrik Armauer Hansen (1841-1912) is credited with discovering that leprosy was a distinct nosological entity. His identification of the bacillus M. leprae in 1873 was the first identification of a bacterium as the causative agent of a human disease. Legislation was introduced in Norway in 1877 and in 1885 requiring leprosy- affected people to be hospitalised. In 2,858 people in a population of 1,500,000 were diagnosed with leprosy in Norway and by 1906, there were 577. The diminution of the disease by the end of the nineteenth century became instrumental in convincing the rest of the world of the value of legislation and isolation measures along the lines of the Norwegian model. (Richards 1977; Gussow 1989; Irgens 1984; Andresen 2004; Gould 2005)

In 1897, at the First International Leprosy Congress, held in Berlin, the following resolution was introduced: “In countries in which leprosy forms foci or has great extension, isolation is the best means of preventing the spread of the disease. The system of obligatory notification and of observation and isolation, as carried out in Norway, is recommended to all nations with local self-government and a sufficient number of physicians.” The resolution, proposed by Hansen, was passed by the congress on the basis of the damage that leprosy caused in a community. It was also proposed because of the perceived success of the Norwegian approach to the disease. So the Norwegian model was adopted by the rest of the world.

This international attention on leprosy in Norway then connects Norwegian models of isolation with those adopted, for example, by the Americans at Molokai in Hawaii in 1866 and on Culion in the Philippines in 1906. Many other leprosaria established at the end of the nineteenth century invite us to compare these different places and ask how they were influenced by the Norwegian model and how they differed from it. One of the most interesting questions for current research is to understand how the relatively liberal regime for isolation of leprosy sufferers in Norway became transmuted into such a harsh regime elsewhere.

One hundred years later, the European Federation of Anti-Leprosy Associations (ELEP) formed in 1966. It was composed of eleven private organisations. The founding organisations were based in Europe. Later those based in Canada, North America, Japan and Taiwan would be admitted to the fold. Comité Exécutif International de l’Ordre de Malte pour l’Assistance aux Lepreux (CIOMAL), Switzerland, could trace its lineage back to the Crusades; The Leprosy Mission (TLMI) which was based in the UK, Fondation Père-Damien (FOPERDA), and Les Amis du Père Damien (DFB), Belgium, all looked back to the mid-nineteenth century for their inspiring founders. The Leprosy Mission had given birth to offshoots in Canada and North America and reached into India and most of Asia. The Order of Charity, France, (AFRF), rose out of the ashes of World War II, producing its own children in Amici dei Lebbrosi (AIFO), Italy, Fondation Luxembourgeoise Raoul Follereau, (FL), Luxembourg, and Fontilles Lucha contra la Lepra, (SF), Spain and reaching into French-speaking parts of Africa and the Caribbean. The Order of Charity, France (AFRF) and Aide aux Lépreux Emmaüs-Suisse (ALES), Switzerland, were Catholic and grew out of the notion of Christian Social Action. The giant of the group, especially in terms of disposable funds, Deutsche Aussatzigen Hilfwerk (DAHW), emerged from war-torn Germany and aspired to be secular in orientation. The founding organisations were, as follows:

Aide aux Lépreux Emmaüs-Suisse (ALES), Switzerland;

Amici dei Lebbrosi (AIFO), Italy;

Comité Exécutif International de l’Ordre de Malte pour l’Assistance aux Lepreux (CIOMAL), Switzerland;

Deutsche Aussatzigen Hilfwerk (DAHW), Germany

Evangelische Leprahilfe

Fondation Père-Damien (FOPERDA)

Hartdegen Fund

Les Amis du Père Damien (DFB), Belgium

The Order of Charity, France, (AFRF), France

The Order of Charity, UK

The Leprosy Mission (TLM) Great-Britain

See http://www.ilepfederation.org/ for up-to-date information about the International Federation of Anti-Leprosy Organisations ILEP

Notes

*1 This includes the following countries: Albania, Andorra, Armenia, Austria, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Belgium, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Bulgaria, Croatia, Cyprus, Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Georgia, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Iceland, Ireland, Israel, Italy, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Malta, Monaco, Montenegro, Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Portugal, Republic of Moldova, Romania, Russian Federation, San Marino, Serbia, Slovakia, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Tajikistan, the former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia, Turkey, Turkmenistan, Ukraine, United Kingdom, and Uzbekistan

Sources

Charles Creighton, A History of Epidemics in Britain, (London. Frank Cass. 1965).

Zachary Gussow Z, Leprosy, Racism and Public Health: Social Policy in Chronic Disease Control, (San Francisco and London: Westview Press, 1989).

Tom A Mendum, Verena J Schuenemann, Simon Roffey, G Michael Taylor, Huihai Wu, Pushpendra Singh, Katie Tucker, Jason Hinds, Stewart T Cole, Andrzej M Kierzek, Kay Nieselt, Johannes Krause, and Graham R Stewart, “Mycobacterium leprae genomes from a British Medieval Leprosy Hospital: Towards Understanding an Ancient Epidemic”, BMC Genomics 15 (2014): 270 http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2164/15/270

Rachel Reader, “New Evidence for the Antiquity of Leprosy in Early Britain”, Journal of Archaeological Science 1.2 (1974): 205-7.

Jakub Likovský, Markéta Urbanová, Martin Hájek, Viktor Černý and Petr Čech, “Two Cases of Leprosy from Žatec (Bohemia), dated to the turn of the 12th Century and Confirmed by DNA Analysis for Mycobacterium leprae” Journal of Archaeological Science 33.9 (2006); 1276-1283.

Charles A Mercier, Leper Houses and Medieval Hospitals, (London: H K Lewis, 1915).

Vilhelm Møller-Christensen, Leprosy Changes of the Skull, (Odense UP, 1978).

—-, Evidence of Leprosy in Earlier Peoples, (Charles C. Thomas, Publisher, 1967).

—-, Ten Lepers from Næstved in Denmark: a Study of Skeletons from a Medieval Danish Leper Hospital, (Danish Science Press, 1953).

Vilhelm Møller-Christensen and Daniel Weiss, “One of the Oldest Datable Skeletons with Leprous Bone-Changes from the Naestved Leprosy Hospital Churchyard in Denmark” International Journal of Leprosy 39.2 (1971): 172-182.

George Newman, On the Decline and Final Extinction of Leprosy as an Endemic Disease in the British Islands, (London: Royal Historical Society, 1895).

Carole Rawcliffe, Leprosy in Medieval England, (London: Boydell and Brewer, 2006).