Norway

As Norway emerged as an independent nation, it became very conscious of the health and well-being of its peasantry, including those suffering from leprosy in the western coastal fishing communities. In 1816 Johan Ernst Welhaven (1775-1828) wrote a report on the shameful living conditions at St Jørgen’s Hospital in Bergen, which had sheltered leprosy affected people since the fifteenth century, and in which he described the asylum as a “graveyard for the living”.

In 1836 the Bergen community proposed that the parliament (Stortinget) build new nursing homes for people with leprosy. A Royal Commission was established and Dr J J Hjørt (1798 – 1873) was commissioned to research the nature and treatment of cutaneous diseases in other countries. He had some expertise from his visits to leprosy-affected districts in Norway. As a result of his studies, he made recommendations in 1832 to the government for stemming the progress of the disease.

Daniel Cornelius Danielssen

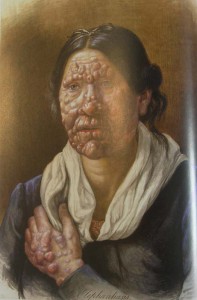

Daniel Cornelius Danielssen (1815-1894) began working at St Jørgen’s Hospital in 1839 and together with Carl Wilhelm Boëck (1808-1875), Professor of the Faculty of Medicine in Oslo, they produced what Ruldolf Virchow described as the beginning of biological knowledge in leprosy. They produced a clear account of leprosy as a scientifically investigated disease. Their work was based on extensive and systematic analysis of its effects on the body through autopsies and comparisons drawn from their studies of leprosy from Boëck’s travels to parts of Europe where leprosy persisted. Their most notable publication was “Om Spedalskhed” (Christiania 1847), which was translated into French as “Traité de la Spedalskhed ou Elephanthiasis des Grecs” (Paris 1848). This was accompanied by an “Atlas Colorié de Spedalskhed (Elephantiases des Grecs)”, which contained 24 lithographs by J L Losting (1810-1876). Their studies of the pathological anatomy of the disease classified two principal types, the tubercle and the anaesthetic. They attributed the cause of leprosy to an inheritable dyscrasia of the blood that was capable of latency only to emerge in unfavourable living conditions. Based on observations of leprosy amongst clusters of families in Norway, they concluded that it was a constitutional condition that would develop in those with a hereditary disposition. They strongly denied the possibility of its contagiousness, citing their experience at St Jørgens of hundreds of people and the absence of a single instance of contagion. They concluded that in order to control the disease, there needed to be a system of registration, isolation in nursing homes, and sexual segregation. In 1850, the medical committee recommended that marriage for leprosy-affected people and their descendants through three generations be prohibited.

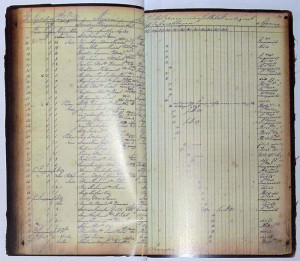

Register of leprosy patients from Nordre Bergenhus Amt (1856-1868)

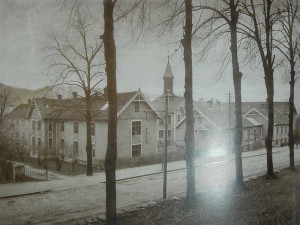

In 1842 the Commission decided that, in addition to St Jorgen’s, the Lungegaardshospitalet, founded in 1845 and in use from 1849, be dedicated to research; and three additional hospitals be created. They were Reitgjerdet, in Trondheim (which, although it had existed since the thirteenth century, was enlarged in 1861 and operated until 1920); Reknes, in Molde (which was built in 1713, but enlarged in 1861 and finally closed in 1895); and Pleiestiftelsen for spedalske no 1 in Bergen (constructed in 1857 and still standing).

In 1854, Ove Guldberg Høeg (1814 – 1863), the first medical superintendent for leprosy was appointed to be responsible for the new national leprosy register, which was established in 1856. This register was the first of its kind in the world and a benchmark for epidemiological research. In 1856, 2,858 people were diagnosed with the disease.

One of Losting’s beautiful portraits of a woman in Bergen’s Leprosy Asylum

Gerhard Henrik Armauer Hansen (1841-1912) is credited with discovering in 1873 that leprosy was a distinct nosological entity and that the lepra bacillus, Mycobacterium leprae (M. leprae), was the specific cause of the disease, although he was never be able to satisfy Koch’s postulates. In 1870, Hansen had travelled to Bonn and later to Vienna for advanced training in histopathology and on returning to Norway, he worked with biopsy specimens from patients with leprosy. In Leprosy: in its Clinical and Pathological Aspects published in 1895 (Bristol: John Wright), he states emphatically that “If one examines, microscopically, sections or teased preparations of fresh nodules, one sees little else but cells, with distinct nuclei, usually of the size of a while blood corpuscle, or rather larger … With a higher power, one sees in the fluid of the preparation small straight rods, which are not destroyed by addition of potash. These are the lepra bacilli, and thus they were discovered in the year 1871.” (p 31). Subsequently legislation to isolated people with leprosy was introduced in Norway in 1877, and in 1885. The diminution of leprosy in Norway by the end of the nineteenth century seemed to demonstrate the effectiveness of the Norwegian system and became instrumental in convincing the rest of the world about the value of legislation and isolation measures.

Pleiestiftelsen No 1, Kalfarveien 31 in Bergen

In 1873, a visitor who had come from India to Norway to observe and compare Norwegian approaches to leprosy with British approaches in India, Henry Vandyke Carter, clearly indicated the standing that Norwegian experts on leprosy were accorded by the rest of the world. He wrote:

“At the present day in no other part of the world, so far as I am aware, are there equally complete, well-conducted, and successful leper-asylums as in Norway; and the physicians in charge are often eminent men, versed in modern science and of European repute. These advantageous conditions form a most striking contrast with what is known of the arrangement and direction of the lazarettos of old … here is a decisive experiment, conducted in the eyes of watchful Europe by a nation which, though small in numbers, has yet acquired a high position in the intellectual ranks of the age.” (Carter)

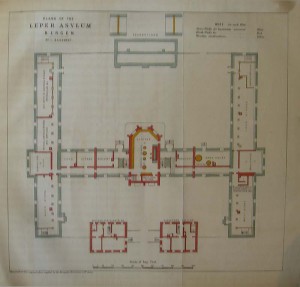

Plans for a leprosarium in Bergen

During Carter’s visit, Hansen, to whom Carter referred as “one of the ablest observers I have met with”, was engaged in “a series of enquiries which cannot but throw much light upon the origin and nature of leprosy” and may in fact show that leprosy is a “specific disease”. This footnote comment in Carter’s report heralds the great “breakthrough” in leprosy research: the discovery of the mycobacterium M. leprae.

In 1897, at the First International Leprosy Congress, the following resolution was introduced: “In countries in which leprosy forms foci or has great extension, isolation is the best means of preventing the spread of the disease. The system of obligatory notification and of observation and isolation, as carried out in Norway, is recommended to all nations with local self-government and a sufficient number of physicians.” The resolution, proposed by Hansen, was passed by the congress on the basis of the damage that leprosy caused in a community. It was also proposed because of the perceived success of the Norwegian approach to the disease. So the Norwegian model was adopted by the rest of the world.

Attendees at the International Leprosy Congress in Bergen, 1909

This international attention to leprosy in Norway then connects Norwegian models of isolation with those adopted, for example, by the Americans at Molokai in Hawaii in 1866 and on Culion in the Philippines in 1906. Many other leprosaria established at the end of the nineteenth century invite us to compare these different places and ask how they were influenced by the Norwegian model and how they differed from it. One of the most interesting questions for current research is to understand how the relatively liberal regime for isolation of leprosy sufferers in Norway became transmuted into such a harsh regime elsewhere.

Program for the Second International Leprosy Congress in Bergen, 1909

Another question that should be examined relates to the way in which an examination of leprosy in a society sheds light on the very nature of that society. The measures adopted against leprosy in Norway occurred at a time when Norway was just starting to see itself as an emerging nation and as such had the energy to tackle social and economic problems. If Zachary Gussow is right when he states that “The history of leprosy in Norway is part of a history of Norwegian nationalism”, then to make use of the documentary record to study leprosy in Norway is to come to some understanding of Norway itself. (Gussow 69)

Sources

Report on Leprosy and Leper Asylums in Norway: with references to India by Henry Vandyke Carter (London: G E Eyre and W Spottiswoode, 1974)