Africa

Batsutoland (Cape Colony)

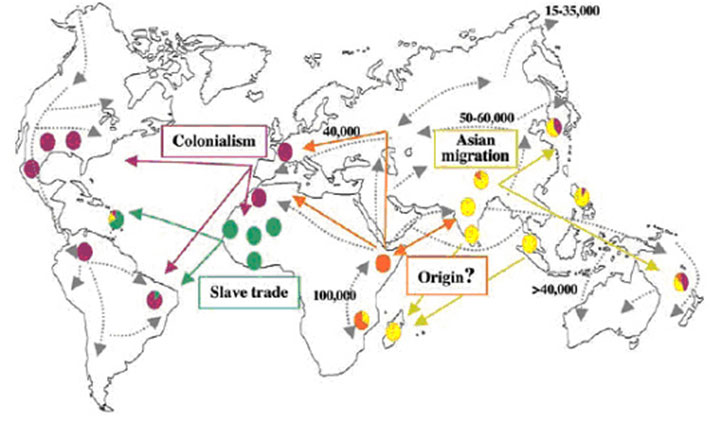

On the basis of current genetic studies of the genome of M. leprae, it appears that leprosy has spread from Africa to the rest of the world. One strain of leprosy can be traced from the Western parts of Africa to islands in the Caribbean, travelling along the routes taken by the slave trade. The same strain was also conveyed into Portugal and Spain and back again into West Africa. On the other side of the continent, another strain of M Leprae has travelled between East Africa and India. Archaeologists have found bones that show the characteristic damage caused by leprosy in the Middle East and in India. Between the sixteenth and eighteenth centuries, leprosy spread from Africa to Santo Domingo, Cartagena, Jamaica, parts of South America, and the south of the North American continent.

Batsutoland (Cape Colony)

The island of Cape Verde, situated between Portugal and Africa and the Caribbean, and a stopping off point for early sea-going explorers and traders, exemplifies both the spread and the persistence of leprosy. In 1531, the king of Portugal appointed a caretaker of “orphans, hospitals, chapels, monasteries and leprosaria on the islands of Cabo Verdi” (Loretti, and Garbellini). A special law was passed establishing a leprosarium on San Antâo, Cape Verde and ordering a census of the leprosy patients living on the islands. Leprosy obviously remained because four hundred years later, in 1950, there was a need for Promin treatment in Cape Verde and new leprosaria were opened in San Antâo and Fogo, Cape Verde. By 1964, the leprosaria on San Antâo and Fogo (Cape Verde) were closed (Loretti, and Garbellini ).

Batsutoland (Cape Colony)

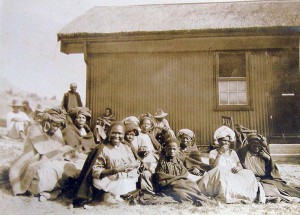

How did Africans respond to the disease? John Manton cites Methodist Missionary and epidemiologist Frank Davey’s impressions of Eastern Nigerian reactions to leprosy infection in the Abua, Item and Etiti Ama areas of Owerri Province, a short distance from Uzuakoli:

In the Calabar Province [where the famous Itu leprosarium, founded in 1926, was based], the attitude of the people to leprosy is one of apathy. [People with leprosy] are not feared, contact with them is permitted, and there is in consequence a high incidence of leprosy. Among the Ibos of the Owerri Province, some diversity of thought exists. There is a widespread belief in a supernatural origin to leprosy. The disease is believed to be a curse from the spirit world, and in some villages the curse is believed to be of so dreadful a nature that the [person with leprosy] is denied that right of resurrection into the spirit world which other mortals share.

Rhodesia

Among such people, leprosy control should be a simple matter, yet it is surprising to find a considerable amount of apathy among the people in spite of their religious beliefs regarding the disease. Thus at both Item and Etiti Ama, [people with leprosy] were found in the village, though it was apparent that well established cases of leprosy were regarded with abhorrence.

The West began to take notice of leprosy in Africa in the mid-nineteenth century. Andrew Davidson, for example, told readers of the Edinburgh Medical Review that the dispensary of Antananarivo, in Madagascar, had treated one hundred people in 1862. He remarked that what had been considered an historical disease was “again beginning to show itself in various localities in the old and new worlds.”

Tanzania

When the British Empire Leprosy Relief Association (BELRA) was formed in 1924, one of its activities involved visiting leprosy asylums in Africa to offer medical advice. Frank Oldrieve visited West Africa in that same year and formed branches of BELRA in Nigeria and the Gold Coast. He made sure that a doctor was appointed in each Colony as secretary and leprosy expert (Rogers, 14-15). Then three years later, he toured from Cairo to the Cape, through the whole of British East Africa and South Africa. By then BELRA claimed to be treating 158 000 people with leprosy “in our African possessions” and administering 100,000 doses of Alepol. (Leprosy Notes) In 1927, Dr Robert Cochrane also travelled through East Africa from Egypt to South Africa and to North and South Rhodesia. He gave advice to leprosy workers and wrote full reports on anti-leprosy work in each area. (Rogers) In 1938, Dr Ernest Muir (BELRA’s Medical Secretary) spent six and a half months on a trip through East Africa, going as far south as Tanganyika. He also visited Malta and Aden (Rogers 15).

After the Second World War, Ernest Muir returned to England from the West Indies with samples of a new drug – Diacetyl Diamionodipenyl Sulphone (DDS) or Dapsone. Dr Frank Davey took some samples back to Africa to try on his patients in Nigeria. With the availability of dapsone, which could be administered orally, and as part of the WHO programme against leprosy, UNICEF was asked to support specific anti-leprosy initiatives. Mass campaigns were extended over vast territories, treating people in the hundreds of thousands.*2 By 1958, the Regional Director for the African Region, Dr Cambournac, was optimistic that “in the near future all leprosy cases in the Region would be under regular treatment.” But before very long, the problem of dapsone resistance became apparent.

Even when the effective multidrug therapy became available, there were an estimated 3.5 million people with leprosy in the region. The health infrastructure of many countries continued to be poor. General health workers knew little about leprosy and its control, and stigma persisted. Today, there are still about 30,000 new cases being detected in the African region each year. Leprosy complications which result in irreversible disabilities still affect about one million people in Africa, often, the most vulnerable people living in poor areas. The disease persists as a source of social stigma, discrimination and poverty. Ninety percent of beggars in the cities of Africa are cured of leprosy but have irreversible disability.

Notes

*1 The countries in the WHO African Region are as follows: Algeria, Angola, Benin, Botswana, Burkina Faso, Burundi, Cameroon, Cabo Verde, Central African Republic, Chad, Comoros, Congo, Côte d’Ivoire, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Equatorial Guinea, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Gabon, Gambia, Ghana, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Kenya, Lesotho, Liberia, Madagascar, Malawi, Mali, Mauritania, Mauritius, Mozambique, Namibia, Niger, Nigeria, Rwanda, Sao Tome and Principe, Senegal, Seychelles, Sierra Leone, South Africa, South Sudan, Swaziland, Togo, Uganda, United Republic of Tanzania, Zambia, and Zimbabwe.

*2 In Angola 13,000 out of 20,000 were receiving treatment and in Mozambique 90% of the known 59,000 were being treated. In the Federation of Mali, 990,000 inhabitants had been examined and 55,000 were being treated. India had examined 12m people and detected 80,000 with leprosy. In Ghana and Niger leprosy treatment was being vigorously pursued. In the Republic of the Congo, the number of arrested cases or those under observation without treatment was greater than the new cases being reported. Similarly reports were proffered by other African countries such as the CAR, Cameroun, Northern Nigeria and Upper Volta. The Americas reported preliminary surveys in Central America, Mexico, Colombia and Ecuador in preparation for control programmes in 1960.

Sources

A Loretti, and D Garbellini, ‘Leprosy in the Cape Verde Islands’, Leprosy Review (1981), 52: 337-48, p. 338.

John Manton, “Leprosy in Nigeria and the Social History of Colonial Skin”, Leprosy Review 82 (2011): 124-134, page 130.

“An Account of Tubercular Leprosy in the Island of Madagascar”, by Andrew Davidson, Edinburgh Medical Journal 10 (1865): 33.

Sir Leonard Rogers, The Foundation of the British Empire Leprosy Relief Association (BELRA) and its First Twenty-One Years of Work by Sir Leonard Rogers. London: British Empire Leprosy Relief Association, 1945: p 14

Leprosy Notes, 1 (1928): 6.

UNICEF-WHO Joint Committee on Health Policy, “Leprosy: Note by the World Health Organisation; Agenda Item 4.4” JC6/UNICEF-WHO/5 20 April 1953. p. 7 WHO Archives, Geneva

“Report of the Second Coordinating Meeting on Implementation of Multidrug Therapy in Leprosy Control Programmes” Geneva 4-5 Nov 1987, p. 12 [WHO/CDS/LEP/87.2] WHO Archives, Geneva