Culion Leprosy Colony (Philippines)

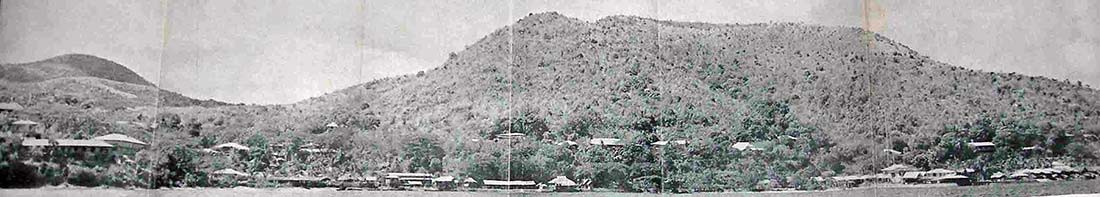

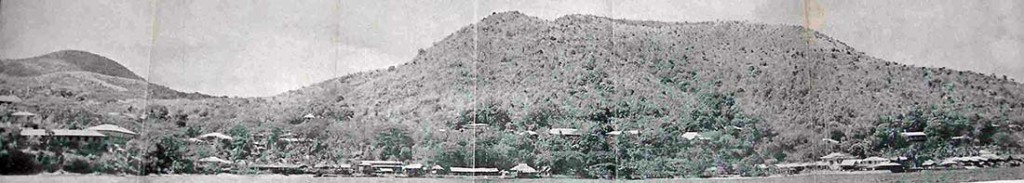

A View of the Island of Culion

At one time, Culion was “the largest and best known institution of its kind in the world, and beyond comparison in area and natural facilities.”

After 400 years of Spanish occupation, the revolt led by General Emilio Aguinaldo declared the independence of the Philippines on June 12, 1898, only to succumb to American occupation a short time later. Under the Americans, a Report of US Senate Committee on the State of Health in the Philippine Islands, in 1899, singled out leprosy as a significant problem.

The US Army survey team investigated suitable sites for collecting and segregating people with leprosy, and initially considered the island of Cagayan de Jolo as suitable, but then settled on Culion Island in the Calamianes, in 1901. The following year, the Second Philippine Commission appropriated funds to construct the leprosarium on Culion.

In 1907, the administration passed a law (Act No 1711) to provide for the compulsory apprehension, detention, and segregation of people with leprosy. The law stated that “The Director of Health and his authorized agents are empowered to cause to be apprehended, and detained, isolated, or confined all leprous persons in the Philippine Islands; and it shall be the duty …” of all police officials to, among other things, report suspects to the health officials, and to give aid to the latter “… in order that such suspect may be subjected to the medical inspection and diagnostic procedure necessary to determine the presence or absence of leprosy.”

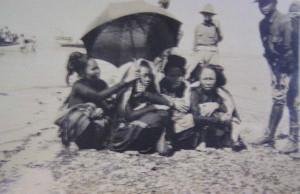

People landed on the beach at Culion (Culion Museum and Archives)

Diagnosis was made without any bacterial examinations, unless someone protested. The law stated that “All protests and petitions shall be given careful consideration and if the diagnosis is questioned, no person shall be permanently removed to the Culion reservation, or other place of segregation or detention, until the diagnosis of leprosy has been confirmed by bacteriological methods.”

Initially, three hundred and seventy people with leprosy were sent from the old camp at Cebu (Nueva Caceres) to Culion:

They were received by the medical officer in charge, four Sisters of Charity who were to act as nurses, and a Spanish Jesuit priest. The patients most in need of hospital attention were place in one of the old residences, while the rest were assigned to newly-constructed nipa-roofed houses. The conditions were described as chaotic, and some of the bare necessities of life were inadequate or lacking. As the years went by, however, conditions were improved and most of the deficiencies were remedied. (7)

Sixty percent of those admitted died in the first four years. (4,473 admitted, 2,674 died) Many had arrived in a very bad condition. They also suffered from beriberi and influenza. (22)

People were brought to the island as a result of “Leper Collection Trips” or expeditions:

Collecting People with Leprosy (Culion Museum and Archives)

For the distant provinces there were periodical “leper collecting trips” or “expeditions” by Coast Guard vessels, in charge of some senior officer of the Bureau of Health, accompanied by a bacteriologist from the Bureau of Science – neither of them necessarily familiar with leprosy. They plus the local health officer at each port of call constituted the diagnostic committee which had to decide who among the cases and suspects presented should be taken to Culion. The examinations were made at whatever time of day or night the vessel arrived and except at Cebu in all sorts of places where the patients had been housed – yards of local jails, temporary huts on isolated beaches, or even less suitable places. The faulty conditions indicated were not due to carelessness of indifference; it was simply impossible in those days to do much better.

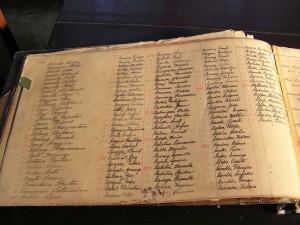

The Register of People Admitted to the Asylum (Culion Museum and Archives)

For decades, in the absence of a cure, leprosy treatment was experimental. From 1906 to 1910, the people were treated orally with chaulmoogra oil therapy; then from 1910 and 1914, they were given injections of refined chaulmoogra oil, based on the treatment developed by Dr Elidoro Mercado of San Lazaro Hospital, and after, from 1914 to 1921, they received the chaulmoogra-based ethyl esters. In spite of initial optimism, none of these treatments proved to be particularly effective. In 1918, the Director of Health reported that of the 1,922 patients treated between 1912 and 1916, only 3 per cent had shown definite or probable improvement; 73 % were unimproved; 21% had quit the treatment. (3)

The Chief of the Sanitarium answered to the Director of Hospitals, and then to the Secretary for Health. The Chief of the Sanitarium had extensive control of both the people with leprosy and those on the island who did not have leprosy. The people had their own internal government based on the typical municipal government of Philippine towns, with a presidente and ten elected concejales, although this was later replaced by the Culion Advisory Board.

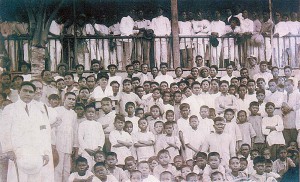

The Boys on Culion 1920 (Culion Museum and Archives)

Originally the Chief of the Sanitarium was the only physician on Culion. Other medical officers were appointed later. When he had to deal with inmates, he was assisted and advised by the elected body that became the Culion Advisory Board. The Culion Medical Board was created in 1922. In 1933 the Culion Welfare Board included the Catholic and Protestant chaplains, the Sister Superior, and the social worker.

The colony had two areas: one that was the “colony proper, where most of the inmates live” and Balala, where the healthy people who serviced the colony lived. There were also two other settlements, Culango and Jardin, where other personnel lived (effectively suburbs of Balala). Apart from the government structures that were part of the colony, much of the built environment on the island looked like any other small town in the Philippines. The colony had its own police, public works sanitation, a general kitchen, post office, public school, inmate teachers, and schools. (11)

Special coins were produced for Culion in 1913, and at first people refused them. “… a law suit and even physical violence were threatened” People threw the coins into the sea to demonstrate their contempt for them, but then during the war, the coins were used throughout the entire region, in preference to what they called “Mickey Mouse” money.

After about 1914, people began to settle into the colony. They farmed and fished, selling their produce to the colony. The Culion Ice, Fish and Electric Company, which began in 1915, was first financed entirely by inmates. Their stores were also profitable. Administrators believed that the people enjoyed relative freedom to pursue occupations that suited them, as in any other village. They had the additional benefit of large areas of land and sea on which to operate. (12)

The doctors feared that children born to people on Culion would contract leprosy, and they attempted to remove the children as early as possible and send them to Welfareville in Manila, so that they could be adopted or fostered.

From 1915, people came before the “Leper Examining Committee” in Manila, which soon earned a reputation for being very hard on people.

The Jones Law was passed in 1916 to formalise the US commitment to granting Philippine independence, but in 1921, when Warren Harding became the President of the US, Major General Leonard Wood and former Governor General William Forbes carried out an investigation into the health of the people of the Philippines that revealed severe public health problems.

The Steamer to the Island

When Leonard Wood became Governor General of the Philippines, on October 15, 1921, and in 1922, he increased the special treatment fund so that Culion could employ more staff, expand and broaden the scope of their technical work, and focus on treatment and research. As a result of new treatments based on the Mercado mixture, several thousands of patients were paroled, although many did not want to leave the colony. Consequently, the negative barrio, Malaking Patag, was established, but it was not a lasting success.

In this period, segregation became decentralised in the Philippines by establishing regional leprosaria and outpatient skin clinics. In addition, attempts were made to care for and to protect the children of patients. Several new committees were set up:

- Philippine Leprosy Advisory Committee

- Philippine Leprosy Research Board

- Culion Medical Board (disestablished in 1933)

- National and local committees for examining negatives

Between 1925 and 1931, the anti-leprosy campaign, later named as the Leonard Wood Memorial Fund, began and the doctors became increasingly optimistic about the possibility of successful treatment:

… at Culion in the Philippines, H W Wade and C B Lara reported 6,000 cases treated in 1921 to November 1926, with 629 recoveries, which with discharges to the end of 1926, would reach over 800. As the result of this unique experience, they concluded that the modern treatment is decidedly superior to the older ones, especially in early cases, and they continued: ‘Though they are admittedly much less effective on well-established, advanced cases, the results obtained in the Philippine Islands during the last few years show that a not inconsiderable proportion of such cases (probably 15 to 20 per cent) can be apparently cured if treated intensively, under proper conditions.” “Recent Advance in the Treatment of Leprosy and its Bearing on Prophylaxis” The Practitioner (April 1928)

The Memorial to Leonard Wood and Hilarion Guia

From 1914 to 1921, Culion enjoyed a reputation for being the largest leprosy colony in the world.

In 1932, when Theodore Roosevelt Jr became Governor General of the Philippines, he abolished the Philippine Health Service, the Office of the Public Welfare Commissioner, and the Tuberculosis Commission and combined these under the Bureau of Health and Public Welfare.

Culion began to decline with the financial crisis of 1933, when staffing was reduced. That year marked the peak of population on Culion, just short of 7,000. After 1935 the population began to decrease because the new provincial leprosaria were opened. The Philippine Congress passed an Act to establish three more leprosy colonies: Tala (Manila), Vigan (Ilocos Sur), and Cagayan, in 1937. In 1938, the prohibition on marriage between those with leprosy and those unaffected was lifted.

The Leprosy Colony in Cebu (Culion Museum and Archives)

From 1936-1941, the average admissions per year to Culion shrank to only 240. By the end of 1941, there were less than 5,500 people on the island. Then during the war years, 1,256 people fled Culion in 1942, and many failed to reach their destinations, while half of the 4,000 who remained died.

In summing up the fifty years of Culion’s existence, in 1956, Dr Lara concluded, “Culion has not, however, achieved its primary goal – i.e., the control of leprosy in the Philippines – in either of the two distinct and successive rules assigned to it: first, as a proving ground for the efficacy of segregation; second, as the center of organized specialized treatment aided by research. In the disappointments and, in certain respects, disillusionments attending its waning years the writer has developed, and still entertains, the hope that Culion may yet contribute to leprosy control by means of prevention of the disease through some kind of immunization.” (36)

In 1952, the segregation law was revised to permit home isolation and treatment under approved conditions.

The Culion Museum still holds a valuable collection of records documenting the history of the colony. Read more about the collection on the History of Leprosy blog.

Source: Extracted from the Republic of the Philippines, Department of Health, Culion Sanitarium, Culion 1906-1956 (Manila: Bureau of Printing, 1956)

Video: Culion Island: a Former Leprosy Colony in the Philippines (Al Jazeera)

Warwick Anderson, “Leprosy and Citizenship”, Positions 6.3 (1998): 707-730.

Jo Robertson, ‘Culion, the “Island of the Living Dead”: or Another Look at Leprosy and Citizenship’ in Astri Andresen, Kari Tove Elvakken and Tore Gronlie (eds.) Politics of Prevention, Health Propaganda, and the Organisation of Hospitals 1800-2000, Bergen: Rokkansenteret, 2005.