China

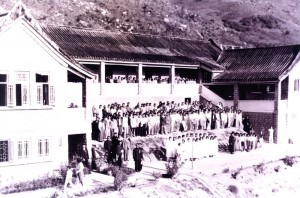

Leprosy detention station, Canton, China, 1931

Only by tracing descriptions of illnesses with symptoms that resemble leprosy can any sense of the presence of what we now call leprosy in China be discovered. (Leung)

Angela Leung states that

Throughout the ancient and medieval periods, ailments with symptoms suggestive of leprosy were described in either symptomatic or configurationist terms in a variety of eclectic combinations: dafeng, li, lai, lifeng, efeng (malignant wind), zeifeng (vicious wind), and so on. In the later imperial period, after the eleventh century, there was the gradual emergence of a term combining a single new symptom-related descriptor, ma (numb), with the configurationist concept of Wind in the more modern compound terms mafeng and damafeng (big numb Wind). (18)

Missionary work expanded in China, between 1900 and 1920. Western missionaries believed that leprosy was more extensive in the southeast, in Canton, Amoy, and surrounding areas.

Sites of mission-sponsored leprosaria in China, 1950

In time, China’s reputation as the seedbed for leprosy with 2.6 million cases was revised. Stanley Browne confessed that “we have all been misled in the past regarding the dimensions of the leprosy problem in China. Former estimates had been based on approximations that extrapolated from studies in the coastal and Yangtse River basin provinces, where the prevalence rates were higher.”

The most influential Chinese story demonstrating how people with leprosy have been stigmatised is one written by the Qing novelist Xuan Nai (1834-1879). This is about Qiu Li-Yu who suffered from leprosy and was ordered to marry in order to sell off the disease, but because she did not have the heart to marry the young man to whom she was betrothed, she was cast out of the house by her father. She became a beggar and was afforded shelter by a young man. She was finally cured by drinking wine in which a snake was drowned. This story was made into a movie, The Leprosy Girl, and was shown widely in the 1940s. *1

The People’s Republic of China

Aerial view of the Pak Sa Lan leprosarium, Macau

As part of China’s nationalised health program, leprosy received specific attention. Stanley Browne eloquently expressed the health situation in China after 1947,

“When the Communists came to power in 1947, they assumed responsibility for a poverty-stricken dismembered country devastated by the ravages of decades of civil war and Japanese occupation, and the resulting social chaos. The medical schools were in disarray, and health services were practically non-existent except for the favoured few in some big towns. Infant mortality was 200 per thousand; the life expectancy was 35 years, and the major causes of death were the transmissible and infectious diseases. Malnutrition was widespread, and agricultural production at a low ebb. There may have been as many as 10,000 ‘Western trained’ doctors in the whole country, but these were mainly concentrated in the large towns and engaged in private practice. There were forty institutions for leprosy sufferers, principally providing custodial care along the then accepted lines; thirty-nine of these were run by ‘foreigners’, that is Christian Missionaries. A quarterly journal on leprosy was published by the Mission to Lepers, Shanghai Branch – an excellent and very influential publication.” (Browne)

Leprosarium, Macau

After the First and Second National Health Conferences in 1950 and 1951, leprosy was included in the countryside review. Official statistics indicated that there were about 50,000 people suffering from leprosy at the time, most of whom were receiving no treatment at all. Between 1950 and 1960, there were nineteen provinces, autonomous regions and municipalities with a prevalence of 1/10,000. These were Guangdong, Yunnan, Hainan, Tibet, Fujian, Guizhou, Jiangsu, Shangdong, Guangxi, Shanghai, Jiangxi, Qinghai, Shaanxi, Zhejiang, Xinjiang, Hubei, Gansu, Sichuan, and Huan. (Yin Dakui)

Leprosy villages were built for housing and treating people with DDS on allocated land and people were compelled to move there. For example, “In the spring of 1956, a leprosy ‘resettlement’ was built up in a remote valley by local villages in Junan County. Nine leprosy patients were forced to resettle in areas of land delineated for them to farm. The first leprosy village run by the government was established in Haiyang County in the winter of 1956.”( Shumin et al.)

Ka Ho, a women’s leprosarium in Macau

Health workers were trained at all levels, from ‘barefoot doctors” to country and provincial doctors in charge of endemic disease control. From the 1970s onward, as the prevalence and incidence of leprosy declined, some leprosy villages were closed or small villages within one county were combined. As a result, the number of villages were reduced to 114, and later, to 80 in the 1980s.

In WHO’s third decade (1968-1977), China entered into the UN system. By 1980, there were still 80,000 registered active patients remaining, with a prevalence of less than 1/10,000.

After 1986, treatment was switched from dapsone monotherapy to multidrug therapy, from institutionalised treatment to community control, from specific therapy to complete rehabilitation and disability prevention, and from control by specialised teams to community participation.

In China, the cumulative number of registered leprosy patients from 1949 until the end of 1997 was 490,000 and that of each province of Guangdong, Shandong, Jiangsu and Yunnan was more than 50,000. Between 1990 and 1997, a cumulative number of 77,000 patients (97%) had received multidrug therapy.

Hay Ling Chau

- Opening of the women’s block at Hay Ling Chau (an island leprosy colony, near Hong Kong)

See also:

Site of Significance: Siao Kan Leprosy Home, in Hupeh [now Hubei] Province, in Central China

Site of Significance: Tai-kam Island

Notes

*1 Extracted by H Y Li from a publication edited by Lu Jian-Min and Ye Gan-Yun, Hubei Scientific Technology Press, 1991

Sources

Stanley Browne, “Medical Services Behind the Bamboo Curtain”, an unpublished paper given at the Eighteenth Meeting of the International Association of Physicians for the Overseas Services, Friday, November 27th, 1981.

Professor Yin Dakui, Vice Minister of Health, the People’s Republic of China, “Achievements and Prospect on Leprosy Prevention and Control in China”, September 7, 1998, Bejing. (Unpublished)

Angela Ki Che Leung, Leprosy in China: A History (USA: Columbia UP, 2008).

Chen Shumin, Liu Dingchang, Liu Bing, Zhang Lin and Yu Xioulu, “Role of Leprosy Villages and Leprosaria in Shandong Province, People’s Republic of China: Past, Present and Future” Leprosy Review 74 (2003): 222-8.

George Thin, Leprosy (London: Percival,1891): 52.