Leprosy, Legislation and Human Rights: Changing Ethical Imperatives

Hawaii Board of Health report on leprosy, 1886.

The management of leprosy has been subjected to changing ethical imperatives. What seemed to be the right thing to do in the late nineteenth century and the early twentieth century, now seems to constitute an inhuman disregard for the person afflicted with the disease. There is scope for an investigation of these ethical imperatives as they were balanced against financial and social concerns in the decisions that were made for the management of the disease. The existence of legislation was part of the enquiry conducted by the Royal College of Physicians in 1867. The College, under the influence of the most modern ideas about disease of the time that were held by Gavin Milroy, found that the isolation of people with leprosy was unnecessary. (Edmond) On the other hand, in some instances, initial measures against leprosy occurred without supporting legislation. This was true in the case of the isolation of Chinese on Daymen Island in Northern Queensland in 1889.

As leprosy was increasingly recognised as a germ disease, leprosy control measures and the principles on which such measures should be based were discussed at the various International Leprosy Congresses (Berlin, 1897; Bergen, 1909; Strasbourg, 1923; Cairo, 1938; Havana, 1948, etc). “Each congress passed resolutions recommending specific measures which countries might profitably include in their legislation. They also aimed at humanizing the existing practices for dealing with leprosy, while at the same time striving to afford the best possible protection of the health of the community.” (4)

Hawaiian legal code, specifying leprosy as grounds for the annulment of a marriage.

When governments faced the prospect of having to take some legislative steps to deal with leprosy, their process of decision making was often accompanied by public debate. The issues debated usually organised themselves around conflicts between the public good and the liberty of the individual. The ethics of detention were contested, but public demand both for protection against individuals with the disease and also for a removal of the sites of detention from proximity to centres of population were combined with continuing uncertainties about the disease (how contagious was it? why did some people get it and others not, even after extended exposure?). These imperatives were weighed against respect for the liberty of the individual. Often decisions could more easily be made if the person with leprosy was poor, of another ethnic group, marginalized and powerless. The independently wealthy posed more of a problem. In many instances, their cases were dealt with discreetly. People were allowed to stay in their homes, but once they came to the attention of the public, further, more systematic, control measures had to be introduced. Those belonging to the ethnic majority also presented a dilemma and the problem of how to deal with them occasioned passionate debate. The compromises that were wrought were never easy ones and were consistently renegotiated, as evidenced in the constant investigations into abuses, scandals, and enquiries that characterise the history of leprosaria. (Kakar)

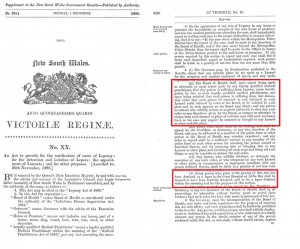

New South Wales government act for the isolation of people with leprosy (1890)

Early legislation for the detention and isolation of people with leprosy was published in the Bulletin Mensuel de l’Office International d’Hygiene Publique. From this we can see that the earliest is in Spain (1878) and Norway (1885). The legislation enacted in Norway was particularly influential as it was produced in the context of a modern approach to the disease that included surveys, registers, hospitals, and medical research.

Legislation was enacted or revised in the twentieth century in Argentina (1928), Australia (Queensland, 1937), Belgian Congo (1938), Dominican Republic (1938), French Guiana (1935), Italy (1923, 1934), Madagascar (1935), Nigeria (1916-1936), New Caledonia, Spain (1933, 1935), Tunisia (1922), Union of South Africa (1931), Venezuela (1939).

East Africa Protectorate ordinance for the isolation of people with leprosy (1913)

Any investigation into the legislation used to detain and isolate people with leprosy must take into account competing notions of public good and personal liberty that changed from the nineteenth century onwards and the accompanying medical and public debates about the ethics of detention and isolation. This is also complicated by differing cultural notions of the liberty of the subject. We also need to include a history of the continuing international debates that stretch into the mid-twentieth century in order to address the question of what sustained the detention, isolation and institutionalisation of people.

An awareness of the issues involved can be determined from such statements as that expressed in 1946 “Where such drastic and unique interference with individual liberty as the segregation of leprosy is practised on medical and public health grounds, it is right that the subject should be reviewed periodically.”

After 1948, with the introduction of the sulphones, the detention and isolation of people relaxed and the laws became dormant or were even repealed in most countries. Nonetheless, people were still being isolated, and in 1954, WHO conducted an investigation in the existing legislation and in their publication, Leprosy: A Survey of Legislation. They reported that “It would not only appear to be difficult to justify some existing practices in the light of our present knowledge of the disease but also, in some instances, they would appear to be in contradiction to the facts regarding its communicability, which show that it is much less infectious than, for example, tuberculosis.”(5) So clearly, people were still being needlessly subjected to legislation that deprived them of their freedoms and rights.

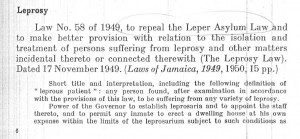

Jamaican legislation for leprosy control program

This 1954 report retrospectively summarises legislation that deals with the “detection of lepers [sic]” (including notification, examination of contacts and suspects, leprosy surveys and censuses); “measures relating to lepers” (including isolation, release and discharge, treatment, trades and callings, marriage and immigration); measures relating to household contacts (including the protection of infants and children and welfare services); and under a miscellaneous category, they include legislative definitions of leprosy, the harbouring and return of escaped lepers, occupational rehabilitation, the role of dispensaries, and leprosarium regulations.

Important themes for further research on this subject include:

- the intersection of law and medicine in the management of leprosy

- the use of people in leprosaria for experimentation and clinical trials (dates from the nineteenth century with the experiment on the condemned criminal Keanu [Robertson])

- the use of legislation in the service of eugenics (especially in Japan), including the sterilisation of people

- the role of the missionaries at the convergence of Christian and Imperial responsibility, especially in India (Buckingham)

- the impact of legislation on property rights, on the family (especially on the right to marry and have children), and on the rights of children (particularly in the preventoria in Brazil)

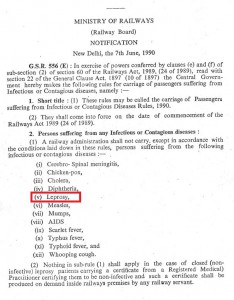

Indian legislation banning people with leprosy from rail travel.

Patient activism and claims for compensation have given rise, for instance, to successful compensation payments to people in Japan. In August 2003, a group of people from Ethiopia, India, America, and the Philippines expressed the injustice of their experiences at a United Nations Subcommission on the Promotion and Protection of Human Rights.

In most recent years, Yohei Sasakawa, the Chairman of the Nippon Foundation, in his capacity as the WHO Goodwill Ambassador for Leprosy Elimination, has drawn international attention to the human rights of people with leprosy. In August 2005, the UN Commission on Human Rights adopted a resolution requesting that all governments act to end discrimination against leprosy-affected people. In June 18, 2008, forty-seven members of the UN Human Rights Council (UNHRC), the successor to the Commission on Human Rights, approved the resolution. On the basis of this, the UNHRC Advisory Committee drew up principles and guidelines for ending discrimination against people affected by leprosy. A follow-up resolution, together with principles and guidelines, was adopted by the UNHRC in September 2010, and this paved the way for the resolution to be adopted by the UN General Assembly in December that year. At the same time, Sasakawa launched a global appeal, which eminent persons and groups throughout the world endorsed and signed to ensure the human rights of people with leprosy. In addition, the Association of People Affected by Leprosy (APAL) was established in India, for people affected by leprosy to organize themselves politically, on their own behalf.

Notes

*1 There are a number of primary sources that shed light on these issues. The Leprosy Commission of the Health Organization of the League of Nations published the Principles of the Prophylaxis of Leprosy (1931); the WHO Expert Committee on Leprosy, in its first report in 1952. There are also authored studies by Jeanselme (1932) and Huizenga (1936).

Sources

Rod Edmond, Leprosy and Empire: A Medical and Cultural History (UK: Cambridge UP, 2006)

Jane Buckingham, Leprosy in Colonial South India: Medicine and Confinement

L S Huizenga, Leper Quarterly 10(1936): 17; 11(1937): 3, 71, 146.

E Jeanselme, 1934, La lèpre, Paris

Leprosy: A Survey of Legislation, Reprint from the International Digest of Health Legislation, WHO: Palais des Nations, Geneva, 1954.

Jo Robertson, “The Leprosy-Affected Body as a Commodity: Autonomy and Compensation”, in Sarah Ferber and Sally Wilde (Ed.), The Body Divided: Human Beings and Human “Material” in Modern Medical History (pp. 131-164) (Farnham, Surrey, United Kingdom: Ashgate Publishing, 2011).

P D Winter, International Journal of Leprosy 17 (1949): 253.