Detention, Isolation, Institutionalisation

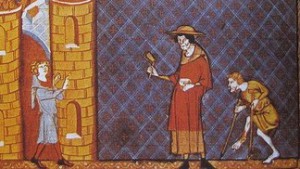

Leprosy in medieval times. Source: https://actu.epfl.ch/news/unraveling-the-genetic-mystery-of-medieval-leprosy/

Throughout much of the nineteenth century, people who were diagnosed with leprosy were detained, isolated and institutionalised.

But had this always been the case?

In Europe in the medieval world, people with leprosy were to be found around towns where they would beg for a living. Some alms houses and monasteries gave them shelter, but if they wished to remain, they had to live by the rules of the monastic order. Rawcliffe (2006) argues that the medieval lazarettes offered a monastic refuge for the leprosy affected, in keeping with what was considered an acceptable and praiseworthy way of life.

YouTube: Leprosaria: The Lost Leprosy Hospitals of London – Professor Carole Rawcliffe

Although the unabated symptoms of leprosy were unsightly and frightening, people were not universally shunned and rejected. Some societies have had more tolerance for people with the disease than others. The biggest problem occurred when people became so affected by the disease that they were unable to make a contribution to the smooth running of their household or family grouping. Then people would either be rejected or they would exile themselves from their families and villages. Begging was considered an option in some societies.

That is not to say that people were not ostracised and treated shamefully. There are many terrible stories of neglect, rejection, cruelty, and a denial of humanity, and these are not stories that belong to the past alone. Before medication began to modify, if not halt the progress of the disease, many of the symptoms would produce a natural repugnance in observers. Generally, they were shocked when they encountered the disease for the first time.

In countries such as India and China, people with the disease clustered together and supported each other. In India, these groups were well organised. In China, people were to be found begging at the city walls. Whatever they would earn would be taken back to their communal dwelling as a contribution towards their subsistence.

In Japan, people with leprosy were to be found around the hot springs.

Itinerant people with leprosy, Japan

In some societies, traditions of benevolence towards those with leprosy had a long-standing history. European practices of establishing charitable hospitals as havens carried over into the new world. In Seville, the San Lazaro Hospital, established in 1248 and still caring for patients until the 1930s, served as a prototype for the Spanish leprosy hospitals in the New World. In the Spanish possessions, leprosy hospitals were established on the island of Hispaniola (1520), in Mexico City (1521), Lima (1563), Cartagena, Colombia (1592), Cuba (1617), Venezuela (1626), Argentina (1778), and in Louisiana (1776), when it was a Spanish possession. In the Portuguese tradition, the Hospital dos Lazaros da Bahia (later Dom Rodrigo José de Menezes) 1852, in Brazil.

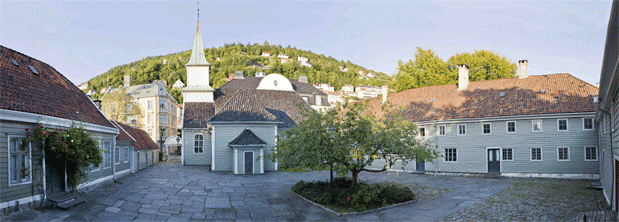

St Jørgen’s, Bergen (Source: The Leprosy Museum)

In the nineteenth century, the Norwegian isolation system received a great deal of international attention, as a model for other countries. This reforming approach to the problem of leprosy began when in 1816 Johan Ernst Welhaven (1775-1828) exposed the shameful living conditions at four hundred year old St Jørgen’s Hospital in Bergen, as a “graveyard for the living.” Twenty years later, the Bergen community petitioned parliament to build new nursing homes for people with leprosy, a royal commission was established. As part of this, Dr Jens Johan Hjørth (1798 – 1873), surveyed leprosy in 1832, traveled abroad to research the treatment of cutaneous diseases, and made recommendations to the government for stemming the progress of the disease.

Inside St Jørgen’s Leprosy Asylum (Source: The Leprosy Museum)

Subsequently, leprosy control in Norway focused on a system of medical registration, legislation, hospitals, and research. Further surveys were conducted in 1836, 1845, and 1852, and a medical superintendent for leprosy, Ove Guldberg Høegh (1814 – 1863), was appointed to be responsible for a national leprosy register, established in 1856. St Jørgen’s Hospital and three additional hospitals, as well as a research hospital, were dedicated to leprosy. Daniel Cornelius Danielssen (1815-1894), Carl Wilhelm Boëck (1808-1875), and Gerhard Henrik Armauer Hansen (1841-1912) all produced key publications on the disease. Danielssen and Boëck produced Om Spedalskhed (Christiania 1847) in which they attributed leprosy to an inheritable dyscrasia of the blood. They believed that it could remain latent until it emerged in unfavourable living conditions. They then reasoned that if individuals carried this “dycrasia”, they should be stopped from reproducing and passing it on to their children. They believed that sexual segregation was a necessity, so in 1850, the Norwegian medical committee recommended that the marriage of leprosy-affected people, and their children and grandchildren, be prohibited.

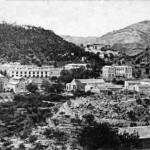

Pleiestiftelsen for Spedalske Nr 1 was constructed in 1857.

When Gerhard Henrik Armauer Hansen (1841-1912) identified the bacillus M. leprae in 1873 as the causative agent of leprosy, legislation was introduced in Norway in 1877 and in 1885 requiring that leprosy-affected people be hospitalized to stop them from communicating the disease to others. Pleiestiftelsen for Spedalske Nr 1 was constructed in 1857. At this time, 2,858 people in a population of 1,500,000 were diagnosed with leprosy, but by 1906, there were only 577. This diminution of the disease by the end of the nineteenth century became instrumental in convincing the rest of the world of the value of legislation and of isolation measures along the lines of the Norwegian model.

Bergen around 1865, with Pleiestiftelsen for Spedalske Nr 1 and Lungegårdshospitalet visible in the background. (Photo: Bergen Byarkiv)

Amidst concerns that leprosy was becoming a problem in the colonies of the British Empire, the Royal College of Physicians conducted a survey to discover if leprosy was on the increase and also how it was communicated. This resulted in a Report on Leprosy by the Royal College of Physicians in 1867. The committee was presided over by Gavin Milroy.

That these measures targeted the poor and relatively powerless was not coincidental, but the rest of the world hailed these measures as modern and well worth emulating. There was no single and preferred prescription for constructing a leprosy asylum, lazarette, colony, or leprosaria. They were usually constructed to suit local conditions, using the materials at hand, and along the lines that would be acceptable in that particular culture. As a result, there was a great diversity of locations and styles of asylum. Yet ideas about and models of isolation were communicated throughout the world, in publications, such as La Lepre and later Leprosy Notes and the International Journal of Leprosy, and especially at the regularly held international leprosy congresses.

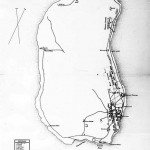

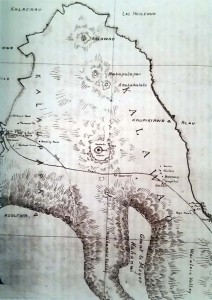

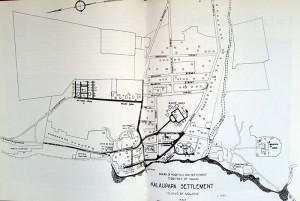

Map drawn in 1895 by M D Monsarrat showing Kalaupapa on the western side and Kalawao on the eastern side of Molokai. Emmett Cahill, Yesterday at Kalaupapa (Honolulu, Hawaii: Editions Limited, 1990), p. 12.

Obviously the Norwegian influence was seminal, but the Hawaiian solution was also an influential early example of isolation. In 1865, in Hawaii, an “Act to Prevent the Spread of Leprosy” was passed. Land on the island of Molokai was purchased to receive the first contingent of leprosy-affected people on January 6, 1866. Between 1866 and 1905, 5,800 were sent to the settlements of Kalawao and Kalaupapa on Molokai. This continued until the legislation requiring involuntary lifetime isolation come to an end in 1969.

Board of Health plan of the layout of the hospital and settlement, Kalaupapa, Molokai, Hawaii. Source: Emmett Cahill, Yesterday at Kalaupapa (Honolulu, Hawaii: Editions Limited, 1990), p. 12.

Not all isolation was enforced. An early example of the benevolent missionary approach to constructing leprosy asylums occurred in India, when Wellesley Bailey, an Irish missionary with the Church of Scotland, became aware of the plight of people with leprosy. This was in 1869, in Ambala, in the Punjab. He and his wife and friends made appeals to people in Ireland, Scotland, and England, and then in India and elsewhere throughout the Empire to raise funds to provide shelter and support for these people. From this, the Mission to Lepers in India grew, supporting leprosy asylums established by other missionary organisations, as well as establishing and supporting new asylums. To mention only a few: Almora 1850, Ambala (the Punjab) 1854, Belgaum Leprosy Hospital, 1862, Subathu, Punjab, 1868, Purulia, Bengal, 1873, Ratnagiri Leper Asylum, Bombay Presidency 1874-75, Naini, Allahabad, UP, 1874, Palliport 1871-1875, Madras Presidency etc. While there were so many in India who sought shelter in these asylums that it was impossible to forcibly isolate everyone with leprosy, increasingly segregation of the sexes became compulsory. The reason for this was to prevent the birth of children who would in turn be infected.

Interested experts throughout the world took note of what was happening in Norway. For example, Henry Vandyke Carter who was a doctor in the Bombay Presidency visited Norway and produced a report on the Norwegian model. Ashburton Thompson from Australia also reported favourably on the Norwegian approach. In India, legislation was enacted on a district-by-district basis so that specially designated, already-existing leprosaria were nominated as places of detention for paupers with leprosy.

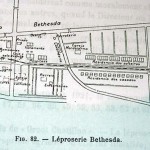

So there were numerous asylums in other parts of the world that differed in appearance and character; for example, Pulau Jerejak in Penang, 1863, Bethesda in Dutch Guiana, in 1899, and Tarvastu in Estonia in 1900. In 1917 the asylum in Carville, Louisiana, to which leprosy-affected people had been sent since 1894. It later became the US Marine Hospital No 66 of the Public Health Service in 1921.

- Palau Jerejak, Penang

- People on Palau Jerejak, Malaysia

- Plan of Bethesda, Surinam

- Bethesda, Surinam

- Carville, Louisiana, USA

- Some of the people isolated on Robben Island, South Africa

- Map of Robben Island showing the lazarette

Title page of the program for the International Leprosy Conference in Bergen, 1909

Legislation and leprosy institutions were influenced by the various international congresses held in Berlin, 1897, Bergen, 1909, Strasbourg, 1923 and Cairo, 1938. The first international leprosy gathering in Berlin in 1897 recognised the contagiousness of leprosy and recommended control of leprosy by segregation of patients with the disease. The second international conference, in Bergen, in 1909, reaffirmed the recommendation for isolation and segregation. It also recommended the removal of children from leprous parents as soon as possible.

Concerned that leprosy presented a threat through emigration from endemic countries, the third international leprosy conference at Strasbourg, in 1923, requested that the League of Nations constitute an international bureau of information and inquiry and collect statistics of leprosy throughout the world and consider international legislation. While recommending that people be humanely isolated, it stressed that indigent and homeless people be isolated and treated in a hospital, sanatorium or agricultural colony.

International Leprosy Conference, Strasbourg, 1923

If we align the leprosaria building programs in different countries with the international conferences and congresses on leprosy, we can see that the modernising impulses of different nations were inspired by the congresses. The years of the early twentieth century mark the period of the “model” leprosy colony or settlement. The Culion Leprosy Colony, in the Philippines, was created in 1906, by the American government in the Philippines. The hospital and agricultural colony of Fontilles in Spain was established in 1907. In the same year, after a leprosy survey that estimated that there were 30,359 people with the disease in the country, Japan introduced legislation aimed at paupers and vagrants with leprosy and began a program of building national leprosaria.

- Plan of the Leprosy Colony on Culion, the Philippines

- Fontilles, Spain 1920 (Source: http://www.u3amoraira-teulada.org/vintage-fontilles-sanatorium/)

- Fontilles, Spain, quarters for married people, 1931 (Source: http://www.u3amoraira-teulada.org/vintage-fontilles-sanatorium/)

- Oshima Seishoen, Japan

In response to the appeal made at the Strasbourg Conference, the Health Committee of the League of Nations began an inquiry into leprosy in October 1925. Two meetings, one in Bangkok, in December 1930 and one in Manila, in January 1931, set the groundwork for coordinating international research and epidemiological studies. In addition, the International Leprosy Association (ILA) and the International Journal of Leprosy were established. This new level of coordination culminated in the Fourth International Conference and First International Leprosy Congress, in Cairo (21-27 March 1938).”

The events of the 1930s gave rise to another spate of legislation and leprosaria construction. In Brazil, in 1929, there were an estimated 24,000 affected by leprosy and between 1930 and 1945, a nationwide network of leprosy colonies and preventorios was established.

- Aimorés, Brazil, 1928

- Itapua, Rio Grande do Sul

- Pavilions, Itapua, Rio Grande do Sul

Japan revised its earlier legislation, in 1931, and by 1941 succeeded in establishing ten state-run sanatoria and isolating 11,383 people by 1943. The national network model was influential in China, in 1957, when at the establishment of the People’s Republic of China, leprosy villages were established throughout the whole country.

- Plans for the lazarette, Bentinck Island, British Columbia (League of Nations Archive)

- Plans for the Spinalonga leprosarium, Greece (League of Nations Archive)

- Plans for the Groot Chatillon leprosarium, Dutch Guiana (Surinam). (League of Nations Archive)

- Plan for the leprosy asylum in Macau (League of Nations Archive)

- Pavilions, Macau

- Pavilions, Macau, long view

When the sulphones were introduced and for the first time there was a treatment for the disease, many of the asylums throughout the world started to empty. However, this was not the case uniformly. In Japan, for instance, people were still isolated until the law was repealed in 1996. On May 11, 2001, the Government of Japan paid £10.4 million pounds in compensation to 127 plaintiffs who had been unconstitutionally detained in leprosy sanatoria.

Sources:

Pousaz, Lionel. ‘Unraveling the genetic mystery of medieval leprosy’. Ecole Polytechnique Federale de Lausanne. Web. Accessed 17 December 2015.