Leprosy and Cultural Production

When people spend a lifetime isolated from society, there is little for them to do to pass the time; subsequently, many found an outlet in some form of creative expression which, in some notable cases, made a significant contribution to the cultural life of their nation. Ikoli Harcourt Whyte is an example of this. He was born in 1905, in Abonnema, in the Niger delta of Nigeria, into the Kalabari tribe and was diagnosed with leprosy when he was fourteen.

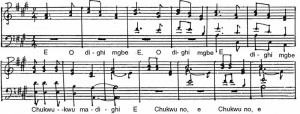

He was sent to Port Harcourt Hospital and then to Uzuakoli Leprosy Hospital. He joined the choir and eventually became its conductor, composing over two hundred choral pieces in Igbo, the commonly-used language at Uzuakoli. This is music that is reputed to have inspired the Igbo during the Nigerian civil war. There are two particular pieces sung by the Choir of the Uzuakoli Leper Colony that are considered to be the most important classical works ever recorded in Nigeria. Ed Keazor pays personal tribute to his inspiration:

At some of my most challenging times – especially when undergoing chemotherapy last year, this music of Harcourt-Whyte was inspirational to me – especially the song “Atulegwu” (never fear), also his composition “Umu gi emebiwo uwa gi” (Oh, God, your children have destroyed the beautiful world that you have created…) is one of the most moving songs I have ever heard and has resonance with several themes of the beauty of this earth destroyed by man’s greed, avarice, covetousness and individualism. It is important also that Harcourt-Whyte’s ministration never included condemnation of other faiths but focused on the simple philosophy love, compassion and empathy for your fellow men. A simple man, he never sought acclaim, money or fame, he believed his life had a purpose beyond the challenges he faced or merely acquiring material achievement, One of the greatest Africans who ever lived, if you ask me. (Ambrose-Ehirim files)

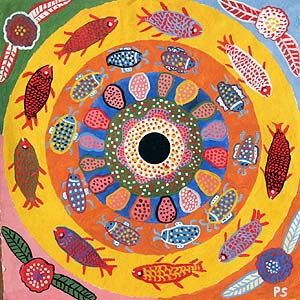

A painting by José Tadeu Bezerra de Oliveira. (WHO Goodwill Ambassador’s Newsletter for the Elimination of Leprosy)

His life has also given rise to other cultural expression, such as Ola Rotimi’s stage play based on his life, Hopes of the Living Dead, in which people with leprosy, drawn from many places throughout the nation, attempt to communicate with each other in their different dialects: the symbolic power of leprosy once again affording a vehicle for the aspiration of national unity.

The people with leprosy in Japan were prolific in their creative expression and extremely powerful and influential in their activism. Their voices represent the largest collection of writings by people who have suffered from leprosy. Anwei Law records that more than 1,000 books have been written, and 1,700 poets have written more than 20,000 tanka and haiku. Each sanatorium published its own newsletter for up to ninety years, and these were filled with poetry, art, and stories. Typical of the perspective of this extraordinary output, the words of Haruko Tsuda, resonate:

“When I look back at my past, my soul is beckoned to the poems I wrote of my father. There are times when I think it would be more natural for me to write about my life as a leprosy sufferer, but my attitude of mind as a poet is inclined more to write about my existence as a “human being.” I want each line and each stanza that I create to be a reflection of the real me, my heart and soul. (IDEA website)”

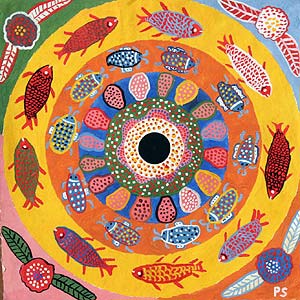

Painting by P. Saravanan, a student at the Bindu Art School, an art school in Southern India that enables those with leprosy to use art as a way of building a new life with financial independence and community respect. (http://www.bindu-art.at)

The same combination of creative outlet and activism is seen elsewhere. In Brazil, for example, Jose Tadeu Bezerra de Oliveira is an artist who dedicates his time to working with long-time physically and mentally disabled residents of the old leprosy colony of Santa Marta, Goiás, in Brazil. He was diagnosed with leprosy and confined in Santa Marta colony when he was twelve years old, in 1983, for although the compulsory isolation of people with leprosy had been abolished in Brazil, the State of Goiás still implemented the law. There he began to paint, and he states that without painting, he would have been “just one more person who self-destructed”.

For him art served to bridge his life in the colony and the life that he now lives outside, in contrast to the predicament of others with debilitating physical disabilities who had little desire to live outside the colony because of the accompanying psychological damage that they experienced. (WHO Goodwill Ambassador) Yet his artistic expression is just one aspect of his multifaceted identity, for as a political activist, he is seeking compensation from the authorities for his totally unnecessary institutionalisation.

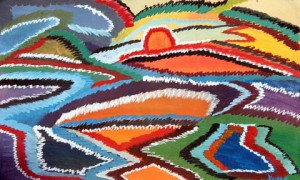

Painting by Y. Uma, Bindu Art School. (http://www.bindu-art.at)

With the advent of a treatment that made the so-called “horrors” of leprosy a matter of history, people who found the full weight of leprosy’s representational past on their shoulders threw it off and reclaimed their individual identities in a manner that humbles those who have ears to listen. And their voices are increasingly being heard.

Sources

The Ambrose Ehirim Files, “Ikoli Harcourt-Whyte 1905-1977” http://ambroseehirim.blogspot.com.au/2010/12/ikoli-harcourt-whyte-1905-1977.html Consulted February 14, 2012

http://www.idealeprosydignity.org/OralHistoryWeb/Books%20Written%20by%20People%20Who%20Have%20Had%20Leprosy.html Accessed February 15, 2012

IDEA Centre for the Voices of Humanity, Freeing Ourselves of Prejudice: In Commemoration of the Second International Day of Dignity and Respect, March 11, 2000 (NY, Seneca Falls: IDEA, 2000).

“Brushing Away the Pain,” WHO Goodwill Ambassador’s Newsletter for the Elimination of Leprosy 53 (December 2011), 4.