Leprosy and Mission

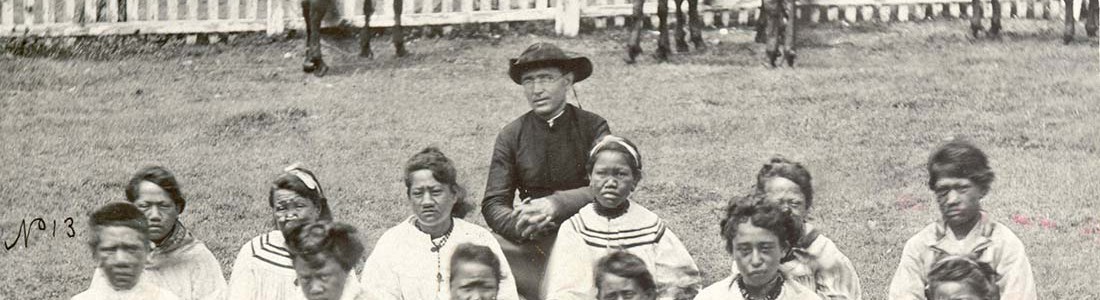

Missionary Herman Landis baptising people affected by leprosy in Nigeria. (Brethren Historical Society and Archives)

There are several significant people who were responsible for founding anti-leprosy charities that went on to contribute to the international work against the disease. They all shared a vision for leprosy work that is unique to leprosy. Anti-leprosy work so often took on symbolic and religious overtones that were sometimes mobilized and more often rejected. These respective visions did not necessarily converge with the visions of others, but generally people who were active in these fields had to have a vocational commitment to, and a sense of mission to, what they were doing, for there were very few material rewards, even in terms of professional status.

Joseph de Veuster

The inspiration of Joseph De Veuster or Father Damien, the Belgian priest who spent much of his life on Molokai, in Hawaii, was born on January 3, in 1840, at Tremeloo, near Mechelen, in the Flemish region of Belgium. His parents were peasant farmers, who expected this son, one of eight, to become a farmer, but instead, he followed his brother into the priesthood and, when the latter became too ill to go to Hawaii as a missionary, requested that he replace him. With the approval of his religious order, he left Belgium, in October, 1863, and after a sea voyage of five months, arrived in Honolulu, where he was ordained a priest. Under his religious name, Father Damien, he spent two years working in the Puna district of the Big Island of Hawaii and another eight years “on horseback and on foot, covering many miles, tending to the spiritual needs of a district that covered 2,000 square miles of mountains, coastal plains, forests and raging streams”. (Cahill)

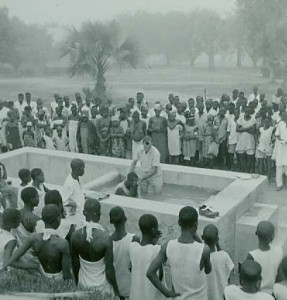

Father Damien with the Kalawao Girls Choir in the 1870s. (Hawaii State Archives)

In April 1873, he was invited with several other priests to attend the dedication of a new church where the bishop spoke of the critical need for a priest to tend to the people with leprosy exiled on the island of Molokai. Four priests volunteered, and Damien was the first to be sent on a rotating basis to Kalawao, Molokai, in May 1873. At that stage, there were 816 people affected by leprosy living there in rudimentary and dispiriting conditions. Once he arrived, he decided that he wanted to stay, and therefore the intended rotation of priests became unnecessary. Damien ended up spending sixteen years working in the colony, improving the basic living conditions of the people, building adequate shelter, and representing their needs and fundamental rights to the parsimonious Board of Health.

The story of his labours and his battles with the authorities is the stuff of legends. So too is his reaction when he noticed the first signs of leprosy on his body, in 1876, and he announced that he had contracted the disease, by addressing his congregation in a sermon as “we lepers”. He died on April 1889, at forty-nine years of age, and his death seemed to indicate conclusively to those in the late nineteenth century who were concerned about the disease, that leprosy, as a germ disease, was communicable.

Another Belgian organisation taking its inspiration from Damien, Les Amis du Pere Damien (APD), was formed in 1954. The founding figure, who was to be indispensable to the formation of ELEP, was the Belgian, Pierre van den Wijngaert. From 1954 until 1967, he was a member of the Congregation of the Sacred Heart, the religious order to which Damien had belonged. Born in 1922, his parents envisaged his future as a missionary and as a priest. On the early death of his father, he was placed in a convent when he was only a year old. He tells the story of being asked by a Dominican nun what he wanted to be when he grew up. He replied, “the Pope”, as this was the most authoritative person that he knew of in the world that he inhabited. He was five years old at the time.

His mother organised for him to be educated with the Picpucien priest, Father Adolphe Steens, who was to become the head of the school of Waudrez-lez-Binche. There he discovered his lifetime hero: Damien, whose story he found so overwhelming that it gave him nightmares. Despite a turbulent adolescence, during which he abandoned his education, he returned to his studies when the German invasion of May 10, 1940, took place. That same year and in spite of the war, he entered the convent, in September, taking the religious name François-Xavier. He spent his novitiate at Tremeloo, the village where Damien had been born. Then he fell ill, at nineteen years of age, with TB, the very same illness that had killed his father and other members of his family. Fortunately, he was able to benefit from the newly-available antibiotics. He was ordained a priest in 1947.

Drawing upon what he had seen of a previous charity where he had served as a chaplain, he proposed and established his own charity called “Les Amis du Pere Damien” (APD), managing to gain the support of several illustrious members to take a place on the Committee, including the president of the Belgian Red Crosse and the Superior General of the Congregation of the Sacred Heart (Picpus) Fathers. He held special fête or charity days in Belgium in order to raise funds, but it was not until 1958 that those funds were put to anti-leprosy efforts. From his description of the committees that were established to manage APD, it is evident that he gained plenty of experience in how to set up and manage a benevolent organisation which was, in his words, innovative and supple, with enough coordination to avoid anarchy and to ensure perfect collaboration between partners. On October 19, 1962, the Damien Foundation (DFB) was legally registered and in 1964, it took over the coordination of all of the Belgian organisations working against leprosy.*1

Van den Wijngaert is credited with being the catalyst for the creation of the federation of anti-leprosy organisations. He was inspired by the post war creation of the Common Market in Europe, and with the support of Raoul Follereau, he rallied support of various anti-leprosy organisations in order to devise a model upon which to form the Federation. He became the first General Secretary of ELEP and remained so until 1989. Father Damien’s, or Joseph De Veuster’s, reputation endures today in Belgium, as a truly outstanding national representative, polling in 2005 as the nation’s “Greatest Belgian”. He was canonised a saint by the Catholic Church on October 11, 2009.

Wellesley Bailey

At almost exactly the same time as Damien was beginning his work on Molokai, in India, an inspiring advocate for people with leprosy emerged from the Protestant tradition. The Leprosy Mission, originally known as the Mission to Lepers, was founded in 1874. Its founding narrative tells of the moment when an Irish missionary, Wellesley Bailey, recounts the moment when he caught sight of people with the disease living across the road from his new home, in Ambala, in the Punjab, in 1869: “The asylum consisted of three rows of huts under some trees. In front of one row the inmates had assembled for worship. They were in all stages of the malady, very terrible to look upon, with a sad, woebegone expression on their faces – a look of utter helplessness. I almost shuddered, yet I was at the time fascinated, and I felt, if ever there was a Christ-like work in this world it was to go among these poor sufferers and bring to them the consolation of the Gospel.”

Bailey’s response is one of horror, fascination, pity, and an immediate sense of purpose – “if ever there was a Christ-like work”, this was it. Bailey’s wife-to-be, Alice Grahame, shared his letters with her three Dublin friends, the Misses Pim. On Bailey’s return to Ireland in 1874, Charlotte Pim began to organise small meetings in her drawing room in order to describe “the terrible condition of India’s lepers, physically, mentally, spiritually, and of what we were trying to do, for just a few of them, at Ambala, in the Punjab.” Donations were given in a tradition of Christian charity, but also in the tradition of subscription for infirmaries and dispensaries that was operative in Ireland in the nineteenth century. These Irish donors were also Protestant, on the fringes of Empire, and part of the very first colonies established by the British, but not Catholic, so not completely marginalised, but respectable, perhaps eager to be members of the class of benefactors and so demonstrate their difference from the less fortunate, as well as their affinity with those who are more secure in their imperial status. Ireland and India were united in the body of Christ in this act of Christian giving, but also as members of the Empire, mystically unified by leprosy.

The Mission began by providing small amounts of funding to Protestant missionary asylums of all and every description where leprosy work was being carried out. This financial support went to a variety of requirements, including housing and staffing. The Mission also purchased its own sites which served as refuges for people with leprosy. As the Mission spread to China and Japan, the name was changed from the “Mission to Lepers in India”, to the “Mission to Lepers in India and the East”, and then to the “Mission to Lepers” and later to The Leprosy Mission. The response from people all over Ireland and then Britain, and very soon India and other parts of the world resulted in what is known today as the Leprosy Mission, International.

Raoul Follereau

Then after World War II another round of inspirational figures emerged: one each from France, Germany, and Switzerland. First of these, Raoul Follereau, was born on 17 August, 1903, in Nevers, in France, to a modest and devout Catholic family. He was only fourteen when his father died fighting in World War I, in 1917. By all accounts, he was a precocious teenager who loved writing poetry and when he received life-changing encouragement as a writer from the playwright and poet Edmond Rostand, the response encouraged him to continue to make direct addresses to people whom he admired. This practice led him to count many people of influence around the world as his friends. As a young man, he stood out as confident and self-assured and with his own very definite and not necessarily obviously popular trajectory.

His self-representation was utterly eccentric. He adopted a distinctive style of dress in his early twenties, influenced partly by the self-conscious style of the students in Montmartre. His physical appearance as a visually eccentric figure with his large floppy bow, tied at the neck, in the form of a cravat, his wide-brimmed hat and his walking stick, with an ivory bear on the handle, were designed to make him memorable. As poet, orator, and passionate advocate of the less fortunate, he espoused and preached Christian values, in the spirit of a lay member of the Catholic Church.

In 1936, he came upon someone whose life would reconcile all of his various motivating impulses. He had been asked to write about Charles de Foucauld, who had died in the Sahara twenty years earlier. Charles de Foucauld had been born in Strasbourg in 1858. He was born into the French aristocracy and served as an army officer in Algeria and Tunisia. When he was twenty-eight years of age, he underwent a spiritual conversion to Christianity and in 1890 joined the Cistercian Trappists. Seven years later, he began to live the solitary life of a hermit and after ordination settled in the Sahara, in Algeria, eventually living with the Tuareg people, in Tamanghasset. He studied their customs and produced several well-respected and erudite publications on their language and culture. His choice of lifestyle and the simplicity of his spirituality inspired the formation of a confraternity within France, known as the Brothers and Sisters of the Sacred Heart of Jesus. He died on December 1, 1916, shot outside his home by a group of Bedouin insurgents.

To write about Foucauld, Follereau went to North Africa to trace his footsteps and in doing so entered into his spirit. In Foucauld’s lifestyle, his erudition, and most of all, in his simple message of love for all men, Follereau found a reconciliation of all his Christian and nationalist aspirations, as well as finding a way of representing France in its colonial context. This change in direction combined with his deepening friendship with the Sisters of Notre Dames des Apôtres simultaneously led him to an awareness of the impact of leprosy, as a disease.

Raoul Follereau’s moment of enlightenment occurred as he travelled in the footsteps of Charles de Foucauld, in 1936, when his driver stopped near a village in order to add water to the car’s engine. Getting out of the car, he saw faces in the bush peering out at him and he beckoned to them to approach, at which point some fled and others continued to peer at him. He asked the guide who they were, and he was told they were “lepers”. In response to all his questions, such as why they were there, and why they were not in a village, and why they were excluded, he was told repetitively that they were “lepers”. It was assumed that their illness was enough of an explanation for everything about them: a self-sufficient reason for their state. He later asked people in authority about their living conditions, and they expressed the view that these people were marginalised and were powerless to do anything about the level of prejudice against the disease. In his own words, he would later say: “And it was then that I realized that there existed an unforgivable crime, a crime deserving of any punishment, a crime without appeal or pardon: leprosy. And it was then that I made up my mind to plead one single cause for the rest of my life: that of the 12 to 15 million men whom our ignorance, selfishness and cowardice have made lepers.”

He was a pioneer in championing the human rights of leprosy-affected people. In 1952, he requested the UN to establish an international convention on the dignity of people with leprosy. Follereau inspired the establishment of other nationally-based anti-leprosy organisations, such as Les Amis du Père Damien (APD, now called Action Damien) and Amici dei Lebbrosi (AIFO). He was also responsible for initiating “World Leprosy Day”, in 1954, a single day, at the end of January, once a year, on which a concerted coordinated media campaign was launched and funds collected for the support of those with leprosy. APD, for example, held their first World Leprosy Day in Belgium on January 31, 1960. Funds raised from this initial effort were then sent to Vietnam, India, Zaire, Benin and Tahiti. Follereau was also instrumental in setting up the leprosy congress organised by the Order of Malta, in Rome in 1956, out of which emerged CIOMAL.

In 1946 Follereau founded the Order of Charity which would become the Raoul Follereau Foundation. In 1968, in a legal document signed before a lawyer, Follereau made the children of two people who had sheltered him in St Etienne during the war, his heirs. The Rameads were herbalists and their son-in-law, who was to take on the burden of this responsibility, was André Recipon. In doing so, Follereau established the Raoul Follereau Organisation or the Order of Charity. In addition to carrying on the various projects that he had established, it was tasked with continuing his annual fund-raising campaign for “the struggle against leprosy and all other kinds of leprosy”, as World Leprosy Day.

Hermann Kober

Another figure to emerge from war-torn Europe, Hermann Kober, was born in 1924 in a small village near Würzburg. He had attended an officers’ school in Potsdam and then served as a soldier in World War II. As a very young man, he was taken prisoner by the Russians and was held captive for five years, unable to return to Germany until 1950. His colleague at DAHW, Karin Roessler remembers that “He did not talk much about his time as a prisoner in Russia. But the stories he told us were positive. He talked about the old women who threw bread over the fence of the camp. He said: ‘we were their enemies, but they saw us young men and possibly thought of their own sons of whom they didn’t have any news.’ ” This way of looking at things, she explains, was typical of him: “this way of seeing things was his motivation: to help people in need, irrespective of their race or religion”. *2

On his release, he studied German literature and philosophy. He married and, with a family of three children, worked as the editor in a local newspaper. As a journalist, in 1956, he heard of the work of the Catholic priest, Dr Feron, at Harar in Ethiopia. This came about as a result of a visit made by two Germans to Ethiopia to attend the silver jubilee of the coronation of Emperor Haylä Selasé I, in November 1955. Count Franz von Magnis, a journalist, and Richard Recke, a theology student, happened upon the St Anthony Leprosarium, at Harar, in 1956. There they met the French priest, Dr Jean Feron, and learnt about his work at the Saint Anthony Leprosarium, which had been founded in 1901 by Ras Mäkonnen.

The visitors were quick to appreciate and respond to the acute needs that they encountered at this leprosarium. When they returned to Germany, they made an appeal through the newspapers. Karin Roessler remembers that “Hermann Kober published the article, and was blamed for the cruel pictures showing wounds and mutilations of leprosy patients”. Undeterred, Kober and some friends decided in January 1957 to establish, in Dr Feron’s name, a “Dr Feron Leprosy Relief Association”, but Feron objected to the use of his name in this context (and perhaps, as a Frenchman, may have been sensitive about making an appeal for support in post-war Germany). Nevertheless, the public responded generously to the appeal. Kober’s wife describes the unprecedented support that they received from the German people, especially from a population that had been brought to its knees by the war. In 1973, Kober also described how that response continued:

Year by year, the financial response of the German people has increased pari passu with the requests for help. In 1958, 1.2 million DM was raised, and 5 centres abroad were helped; in 1964, the amount increased to 4 million DM and no fewer than 90 centres were helped. In 1972, the huge sum of 14 million DM was collected, which helped to support 180 centres. Among the contributors to DAHW we find businessmen who give generously, manual workers and ordinary folk living on small fixed incomes. Youth groups raise money by staging theatrical plays, organizing football matches, etc.

He credited the overwhelming response to the following: “The mass media – radio, television and the press – have shown a great interest in DAHW and have been very generous in their coverage. Journalistic flair and professional connections have been harnessed to the task of disseminating information and arousing interest.” In response to the fund raising and to everyone’s surprise, requests for assistance for work against leprosy also came pouring in from India and other parts of the world. Subsequently, the name of the appeal was changed in August 1957 to Deutsches Aussätzigen Hilswerks (DAHW) (the German Leprosy Relief Association or GLRA) as the appeal for funding and the support to St Anthony’s, then Ethiopia, and other parts of the world, expanded.

Kober had a dual vision for the work against leprosy that was about both treatment and rehabilitation. In Karin Roessler’s words, he took a passionate interest in rehabilitation. His slogan was: “try to find leprosy patients as early as possible, treat and cure them and avoid mutilations. If they are already mutilated, provide them with medical and social rehabilitation so that they can earn their own living”. This led DAHW to establish large urban leprosy control and rehabilitation programmes in India. A leprosy control programme covering the complete area of a sprawling Indian city, such as in Bombay, was one of his innovations. He also had a vision for combined programmes: “Since it was possible to treat and cure leprosy, he thought about using the structures of the national leprosy control programmes, mostly in Africa, for the treatment of other diseases. The disease most virulent at that time was tuberculosis (later in combination with HIV/AIDS).” This was the beginning of combined leprosy/tuberculosis control programmes. His slogan was “two diseases, one approach”. Roessler states that this was greeted with some scepticism: “In the beginning nobody really believed that this was possible, but they [the DAHW Board] were right in the end”.

Kober was one of the original driving forces in founding ELEP. He believed that a federation of organisations was necessary to best use the money raised by the various associations and also to ensure that the “leprosy projects with good connections” were not the only ones to receive all the support, with others left “empty-handed”. Amongst a colourful group, he was strongly individual. Roessler comments that Follereau was a kind of “baroque personality” who called Kober and Recipon his “spiritual sons”, but Hermann Kober was completely different to Follereau: “He was a maker, always restless, looking for solutions, not so much a man of the word, of appeals”.

Kober dedicated over forty years to DAHW (1957 to 1998). He served the organisation in different roles: first as Treasurer, then as Executive Director (until 1994), and finally as President. Until his retirement in 1994, he continued to work as a full-time editor of the local newspaper, juggling two full-time occupations. Roessler remembers that he spent his holidays visiting projects, negotiating with governments, and participating in ELEP/ILEP meetings: “His energy was unbelievable. His family, above all his three children, might have felt neglected. We young people at that time became “infected” by him. We were so excited to help him transform his ideas and visions into reality. He was an absolutely passionate advocate of the cause of suffering people, a really charismatic personality.” As a journalist, Kober was able to mobilise both newsprint and television to make the organisation known. Follereau comments that after the war, Germans were wary of any cult of personality so that Kober deliberately refrained from taking the limelight in DAHW. He concentrated on leprosy and on the people affected by the disease, placing great emphasis on care of the “whole person”.

Marcel Farine

The next European figure was Marcel Farine, the father figure behind the anti-leprosy work of Emmaüs-Suisse. He was born in Moutier, in the Swiss Jura, in 1924, to a poor family, so poor that when he was eight, when they travelled from Berne, to Morges, in Canton Vaud, by Lake Leman, in the freezing winter of January 1932, they travelled in a tarpaulin-covered truck. His father managed to set up a grocery store, and when the time came to educate him, the family situation had improved sufficiently for them to be able to pay for his studies. He remembers beginning school and being laughed at for his Franco-German hybrid dialect. To make up for lost time, his father transferred him to a Catholic school where he quickly caught up, going from third last in the group to fourth in the year. He eventually gained a diploma in administration from the Ecole Supérieure de Commerce, in Lausanne.

He never forgot his difficult childhood, nor the profound faith of his parents, and from an early age, he was interested in social action, within the context of his Catholicism. He believed that “Les années de pauvreté de ma première jeunesse ont ancré en moi l’idée de combattre contre la maladie et la misère, afin d’épargner à autrui les situations que nous avons vécues ou celles, pires encore, dans les pays en voie de développement.”

He moved to the German part of Switzerland in the aftermath of the war, where he saw the plight of many young people arriving in Berne who had left their homes in order to find employment in shops and factories. As a young Christian worker (YCW), he organised support for them so as to break down their isolation and help them settle in. In 1949, he entered the Union Postale Universelle (UPU) where he spent the next thirty years as section chief for technical cooperation, until he left to devote himself totally to Emmaüs-Suisse. The experience that he gained representing the UPU at the United Nations and other international agencies, such as WHO and UNESCO, would serve him well in his charitable commitments. He and his wife reared eight children, in addition to an adopted child of parents with leprosy from Cameroun, whom they sponsored and who went on to become an engineer.

His sense of mission took shape in the freezing cold of winter in 1954, when he was inspired by the famous call made by Abbé Pierre, for solidarity with the poor. Abbé Pierre, born Henri Marie Joseph Grouès, in Lyon, in 1912, was a “father figure” par excellence and without exaggeration: “a legend in his own lifetime”. He had been educated by the Jesuits and taking his inspiration from St Francis of Assisi, joined the Franciscan monastery of Notre Dame du Bon Secours at St Etienne, taking the name, Brother Philippe. Dogged by poor health, he was ordered to join the secular clergy, and in 1939 was nominated vicar of St Joseph’s, in Geneva.

In 1942, he joined the French Resistance during World War II, helping Jews escape the nightmare of Vel d’Hiv, in 1942. He also helped Jacques de Gaulle, the paralysed brother of Charles de Gaulle escape to safety. During this time, he edited a clandestine newspaper Union patriotique indépendante, writing under the pseudonym “Georges”. In order to baffle the Gestapo with another identity, he began to refer to himself as “l’Abbé Pierre”. [i] He was eventually arrested, but he escaped and he joined de Gaulle’s Free French Forces in Algeria. After the war, he became a member of the French National Assembly, but decided his efforts were more effective through the Emmaus movement, which he founded, in 1949, in order to help the homeless and refugees. He believed in helping people help themselves: in “giving people a bed and a reason to get out of it.” He set about developing communities with resources to be self-supporting. He was a deputy of the Popular Republican Movement and was criticised for his left wing politics, but disavowed “left and right”, saying “the only extreme I support is upwards towards heaven.”

In the bitterly cold winter of 1954, during which five million French people were without adequate housing, he made the now famous compelling broadcast that would inspire not only Marcel Farine, but the whole of France. He told his listeners: “My friends, help me: a woman has just frozen to death at three this morning, on the pavement of the Boulevard Sebastopol, clutching the document by which she was expelled from her home the day before…”

Describing this moment, his obituary states that he did not speak as someone making an appeal, but as “an angry prophet challenging the French to heed their moral duty.” Like Gandhi, he claimed that the measure of “a civilised society” was the way that it treated its outcasts: “Abbé Pierre’s energy during that winter of 1954 not only inspired what he called l’insurrection de bonté among the French, which saved people from dying in the streets; he also gained a moral authority over his countrymen which he would retain for the rest of his life.” He became the unofficial spokesman for the homeless, transcending the religious and political differences of his country. He was admired by Catholics, for presenting the best aspects of a living Catholic faith. At the same time, he was also appreciated for his strong criticism of the Catholic Church’s conservatism.

Like Father Damien in Belgium, Abbé Pierre was and is still so admired in France that he has been frequently voted France’s most outstanding figure, a list that he demanded he be removed from. His political position as a Catholic in French politics was probably the extreme opposite of that embraced by the young Follereau, and yet Farine cites them both as encouraging him. Inspired by Abbé Pierre, Farine began Les Amis d’Emmaüs which was officially convened in Geneva, in 1958. L’Aide aux Lépreux Emmaüs-Suisse came into being in 1959. Farine went on to become the first president of Federation of Emmaüs-Suisse, a position that he would hold for thirty-two years. Farine credits the encouragement of both Raoul Follereau and Abbé Pierre for his decision to take on this role of the founding president of ELEP/ILEP and then of Emmaus International, in 1969. He stated that “l’un des devoirs les plus urgents de notre époque est de soutenir les organisations de coopération en faveur des plus pauvres – qu’elles soient d’ordre étatique, privé ou religieux – ou mieux même, de s’engager au sein de celles-ci.”

Like Abbé Pierre, Farine devoted his life to making a difference to people in need, believing that happiness was to be found in a life of giving, as he is cited: “Il y eut des fois où la misère m’a révolté et où j’ai senti monter la colère et la honte, mais aussi où j’ai ressenti une immense joie face à tant d’hommes et de femmes totalement dévoués aux humbles et aux déshérités”, dit encore Marcel Farine. Farine died at eighty-four years of age, on March 27, 2008, a year after his great inspiration, Abbe Pierre, who died at ninety-four years of age, on January 22, 2007.

Notes

*1 Initially APD amalgamated with Damiaanaktie and then “Fondation Belge pour la Lutte contre la Lepre” joined them. The Damien Foundation International for Leprosy Control became international, entering into cooperative relations with third world countries. It also became a completely secular organisation.

*2 I rely on Karin Roessler’s experience and memories of working with Hermann Kober as my source. Karin Roessler, a colleague of Kober’s, worked with him at DAHW from 1972-1998. Email exchange July 1, 2010

Sources

Emmett Cahill, Yesterday at Kalaupapa: A Saga of Pain and Joy (Honolulu, Hawaii: Editions Ltd, 1990), 17.

Pierre Van den Wijngaert, “Comment j’ai fonde ‘Les Amis du Pere Damien,” Amiens: COR, 1996, 14.

http://www.ilep.org.uk/about-ilep/history-of-ilep/ Consulted July 2, 2011

A. Donald Miller, An Inn Called Welcome: The Story of The Mission to Lepers from its Foundation to the Retirement of the Founder, Wellesley C Bailey (Guildford and London: Billing and Sons, 1965).

Jo Robertson, “The Leprosy Asylum in India: 1886-1947,” Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences 64.4 (2009): 474-517.

http://www.vatican.va/news_services/liturgy/saints/ns_lit_doc_20051113_de-foucauld_en.html consulted June 21, 2001.\

Étienne Thévenin, Raoul Follereau: Hier at Aujourd’hui (Paris: Librairie Arthème Fayard, 1992).

Raoul Follereau, trans. Barbara Wall, Love One Another (London: Burns & Oates, 1966).

Association Internationale des Fondations Raoul Follereau: Son histoire; Ses buts (Paris).

Mesele Terecha Kebede, Leprosy, Leprosaria and Society : A Historical Study of Selected Sites 1901-2001 (Addis Ababa: Armauer Hansen Research Institute, 2005).

Hermann Kober and S G Browne, “The German Leprosy Relief Association,” Leprosy Review 44.4 (1973): 177.

http://www.marcelfarine.ch/index_fr_03.htm Extrait du livre: “Les rendez-vous de l’espoir “

“Obituaries: Abbe Pierre” The Telegraph, Monday July 4, 2011 http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/obituaries/1540235/Abbe-Pierre.html

http://www.biographyonline.net/humanitarian/abbe_pierre.html

Pettinger, Tejvan. “Biography of Abbe Pierre “, Oxford, www.biographyonline.net, January 23, 2007. http://www.biographyonline.net/humanitarian/abbe_pierre.html