Purulia (India)

Leprosy asylums were reputed to be isolated and isolating places, but in India not only were they situated at the convergence of medical and missionary discourses, but they were also the sites at which medical knowledge about the disease was forged and disseminated to international networks. Before 1948 and the development of effective chemotherapy against the disease, the leprosy asylums in India not only grew and developed in response to international networks of expertise about leprosy, but at the same time, were productive of knowledge that reinforced and even shifted those same international networks. A dynamic between asylum and medical knowledge ensured that as the asylum changed so did the focus of medical expertise. Furthermore, this dynamic was reflected in the architecture of the leprosy asylum, of which Purulia was an example.

The leprosy asylum at Purulia, in Western Bengal, was opened by the Rev Heinrich Uffmann, a missionary for the German Evangelical Lutheran Mission, known as Gossner’s Mission, in 1884, in response to the many homeless leprosy-affected people in the district. This asylum would find financial support in 1888 from the Mission to Lepers, a British Missionary organisation, which decided to make a permanent grant to the asylum. (Joseph; Robertson) With continued support from the Mission to Lepers, the Purulia asylum would go on to become, by 1948, a model of a modernized institution for leprosy colonies throughout the world. (Rogers, 126) As the ideas about how to deal with the disease changed, so did the asylum, but as the asylum structured itself, ideas about the disease shifted as well.

By 1884, although Hansen had discovered the bacillus, many aspects of the nature of the disease were being debated. Worboys points out that informed British medical opinion, in line with the findings of the Royal College of Physicians, in 1867, tended to regard the disease as not contagious or communicable to healthy people by proximity or contact with the diseased, but influenced by subordinate causes such as environmental conditions. (Royal College of Physicians) These findings built on Danielssen and Boeck’s definitive 1847 work which stated that the disease was due to an “inheritable dyscrasia of the blood.” It was “capable of latency, only to emerge in unfavourable living conditions.” (Danielssen and Boëck)

While the leprosy asylums in India were determined by economies of value that have been discussed elsewhere, their built environment was also governed by what was understood of the logic of the disease. *1

Purulia Leprosy Home and Hospital from the road leading to the main entrance: the leprosy colony is approached by a long road that would have denoted its separation from the rest of the community. (Sharpe)

The choice of site and the choice of structures that would comprise the built environment are both instances of the determining nature of the disease. The status of medical knowledge about leprosy determined the rationale for choice of a site. After the first site was quickly deemed to be too small, the new asylum was planned on “an open elevated spot of land” which was “outside the limits of the municipality, about two miles away from the town.” The site was considered ideal because it had plenty of shade and fresh air: “The perflation of air through the village, the ventilation of the houses, and the sanitary arrangements are satisfactory.” (Report Purulia, p. 71) This rationale, highlighting the importance of fresh air, ventilation, and sanitation, displays sensitivity to environmental notions of disease transmission which may have been influenced by a more modern, elite notion of leprosy. (Worboys)

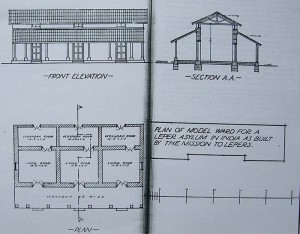

Plan of Model Ward

The most immediate and pressing demand was from the sheer numbers of people who sought shelter in the asylum. The original site, chosen in 1884, had to be moved in 1886 because of the demand from the leprosy-affected people who flocked to the asylum. (Report Purulia 71) The first huts that were built at Purulia on the new site were filled very quickly. Originally there were five houses for men, constructed to receive twelve patients each and three similar houses for women, but in 1891 the women’s houses were overcrowded and more needed to be built immediately. (Bailey 121-4) Again in 1896, overcrowding was a problem necessitating the construction of more new accommodation. By then there were nine houses for the men (each room measured 14×14) and two rooms were half ready. Of the eight houses for women, some were unfinished and already overcrowded, and there was an urgent need for two new houses. (Bailey 16) By 1906 the asylum had sixty buildings.

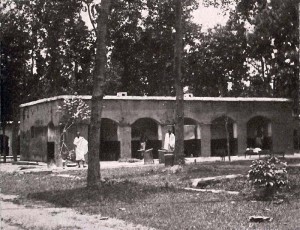

One of the men’s houses: at the time of the photograph, probably in the 1940s, there were three rooms in a house, with four, sometimes five, inhabitants. Around 800 leprosy-affected people lived in the colony.

At the conferences for superintendents of the Mission, ideal structures for the asylums were discussed and a degree of uniformity in construction was established that still catered for regional diversity. Wards were to be constructed from substantial materials such as bricks that were either pointed or plastered. All wood work was to be of sawn timber and the doors and windows made of seasoned timber. The roof had to be rainproof and built from materials that would ensure this. Floors could vary with location. A great deal of emphasis was placed on ventilation which was to be provided by transoms, two end windows and also by low partition walls which did not reach to the roof of the building. Light in the centre room was provided by putting in two windows. Skylights could be added to the veranda rooms. In the homes where the people did not cook for themselves, the veranda rooms would be used for sleeping.

Central Avenue, Purulia Leprosy Asylum

The planning of buildings and the allocation of spaces in the Purulia asylum which evolved over several years also displayed an awareness of the importance of separation: notably the spatial separation of children from their parents, and the not unrelated segregation of men and women. In 1891 although the asylum itself was not secluded from the outside by a wall, the internal spatial arrangement was in two parts. Wards for men were separated by a high wall from the wards for women. After the introduction of effective chemotherapy, by the 1940s, the wall had been demolished and a long tree-lined central avenue separated the men’s and women’s quarters and colour-washed houses for men and women lined either side of the avenue.

Healthy Girl Guides

Homes for boys and girls were situated at a distance from the asylum proper on some rising ground and close to the homes for the doctor, caretaker and teachers. The Mission drew on the experience of Dr Neve in Kashmir who had separated children from their leprosy-affected parents at birth and after some time concluded that the “children of lepers at birth are free from the disease; but unless separated from their parents they are almost sure to develop it within a few years.” (Rogers and Muir 132) This policy was also pioneered in Almora asylum, which was established by the London Missionary Society and supported by the Mission to Lepers. There, with the consent of the parents, children who had not been infected by the disease would be placed in a home, and parents were able to visit them occasionally, without coming into close contact. (Bailey) The intention of Mission was stated by Wellesley Bailey “if we cannot save those in whom the disease has actually begun, we may yet do something to prevent others from falling victim to it.” (Bailey 1887, 89) So from 1890 onwards most asylums in India had what was called untainted children’s homes in which boys and girls were separated from each other and their parents. Asylums also had observation homes for children who showed early, but undefined, signs of developing leprosy. By the 1920s, Purulia included eight separate compounds: for leper men; for leper women; for leper girls; leper boys; untainted girls; untainted boys; and for girls and boys under observation.

The increasing sense of the communicability of leprosy cannot be compartmentalised from this experience in the asylums of the Mission to Lepers. This operational policy found its way into International Leprosy Conference and Congress resolutions from 1906 onwards, both influencing knowledge about the transmission and communicability of leprosy and highlighting ideas about the vulnerability of children to infection.

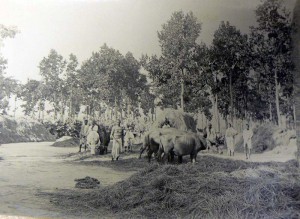

Farming

By the late 1930s, the policy of separation of children from their leprosy-affected parents had blossomed into a success story for the Mission which delighted in claiming that many children were able to be discharged from their asylums free of the disease. In addition, medical interest had grown to the extent that by the 1940s, British doctors who were considered the leading authorities in the field stated that leprosy was essentially a child’s disease. Ernest Muir, who worked at the Calcutta School of Tropical Medicine, wrote that “if all children were kept free of contact with infection for the first ten years of life, leprosy would almost, or entirely, die out of an endemic country within two generations.”

Purulia residents tending buffaloes and cows (1920)

The architectural arrangement of the asylum which placed children born to leprosy-affected people on the boundaries of the asylum also perfectly expressed the liminal space occupied by these children in relation both to the disease and to society. They were outside the asylum proper, but on its boundaries and in proximity to it.

The disease also profoundly affected the spatial architecture of the leprosy asylum to the extent that it increasingly evolved into a self-sufficient space that attempted to cater for all the needs of the people who dwelt there. When people were admitted to a leprosy asylum, they did so for life. While there was little hope of a cure, the disease did not kill its victims, and people generally remained in reasonable health, especially if they received adequate nourishment and shelter.

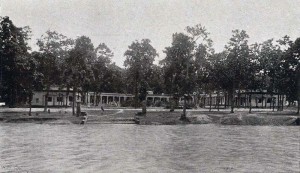

Purulia 1920

One of the most remarkable aspects of this attempt at self-sufficiency consisted of the provision of land for agriculture and the requirement that people occupy themselves usefully in ways that would contribute to the economic independence of the asylum. In this way the asylum gradually mutated into a colony for large numbers of people who were employed in growing their own food, making their own clothes and building and repairing their own homes. This arrangement served the dual purposes of occupying the people and cutting the costs for maintaining the institution.

The farmyard held stacks of rice-straw and the cattle used for ploughing the fields. There was also a blacksmith’s shop, where carts were made and mended and ploughs were repaired. There was also the cobbler’s corner, where sandals were made to protect the nerve-damaged feet of the leprosy-affected field workers from old motor tyres.

Leprosy-Affected People Repairing Roads (1920s)

Undeniably, the regime of the leprosy colony formed its occupants into self-governing productive Christian subjects. In 1908, procedures and self-governance at Purulia were well established. On admission, a patient would be received by the caretaker and then examined by the doctor. The caretaker would arrange for their food and accommodation. Elders were responsible for the behaviour and well-being of those in their wards, and would look over the inmates and report to the caretaker. Caretakers would report to the superintendent. A roll call would be taken weekly. Rice and pice were distributed on fixed days and the shop in the asylum allowed inmates to buy dal, salt, oil, (tobacco and pan) for their own food preparation.

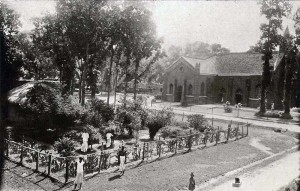

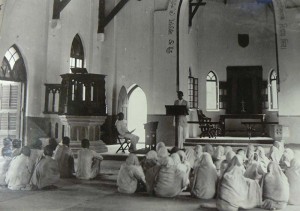

West side of the Church and Garden

Inmates followed a daily routine. There was a daily service at seven in the morning, and from eight to nine, religious instruction and from nine to ten, reading instruction. For those who were ill or with ulcers that needed attention, the dispensary was open and the Indian doctor and his assistant compounders would distribute medicine and also visit the bedridden. There was instruction again for an hour in the afternoon, and outside work, such as tending vegetable gardens or making bedsteads or ropes. The more physically able were employed in digging and clearing the roads, watering trees or tending cattle, as well as raising their own poultry. Time was also spent time reading, singing, and playing indigenous instruments. Children attended school in the asylum and were organised for physical exercises and sports games. The evening concluded with Bible classes and prayer meetings. (Report Purulia 72-4)

Classes for Christian baptism, Purulia

The Church was one of the most outstanding features of the colony and was built in the Gothic style characteristic of Christian churches in India. (Metcalf 58) These photos reveal that there were also separate prayer rooms for men and women.

West side of the Church and Garden: The thatched roof of the men’s prayer room appears to the left. In the 40s there were two little round mud and thatched huts (erected by the patients), one on the men’s side and one on the women’s side. Still standing today in the children’s compound is the most exquisite decorated round mud hut with a thatched roof built by the children as a place of worship.

The hospital wards as seen from the Fraser Tank

At the same time, the absence of excluding walls around the asylum itself meant that the separation between the colony and the outside was extremely porous, and superintendents were constantly writing to each other to say that inmates had turned up in another asylum. People left seasonally in order to beg, visit family, or go to an asylum where sexual segregation was not so strictly enforced. They also left because they were dissatisfied with the food, clothing or rules of one asylum. Other reasons for leaving included refusal to accept the punishment or discipline of the asylum; refusal of permission to marry; family quarrels; caste issues; harsh treatment from attendants or native helpers; or fear of conversion to Christianity. (Roberts 4-6) At the Purulia Conference of Superintendents, in 1908, it was acknowledged that some left to see relatives who lived some distance away or simply because they loved wandering.

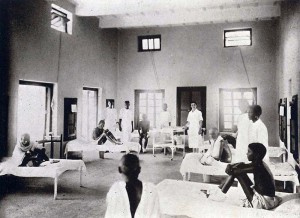

The out-patients’ hospital. The nursing sister with three of the nursing staff and some patients.

The 1920 the Conference of the Mission to Lepers in India devoted considerable time to discussing the nature of the leprosy colony, especially the agricultural colony. At that time Purulia, in Bihar, was the largest asylum belonging to the Mission in India There was a well-equipped dispensary for medical care of people and a hospital for advanced cases. Gardening and field cultivation were activities available to those who were able. (46th Report 10-11) Outside the asylum a small village had sprung up. It was occupied by young married couples, some of whom had grown up in the children’s homes and who now were employed in the asylum. (46th Report 20) By 1922 the Mission claimed that their work had attained such a standard that it had become a model for how such work should be conducted. They concluded that “The inmates are responsive to what is being done for them, and it is gratifying to report that with few exceptions the care and segregation on a purely voluntary basis of such a large number of people has been successful.” (48th Report 6) The agricultural colony became the preferred model of leprosy asylum as expressed at the 1938 International Leprosy Congress in Cairo and in the medical reference books subsequently. (Rogers and Muir) In Brazil, in 1929, a nationwide network of leprosy colonies was established. This network model was also influential in China, in 1957.

The admission wards, where treatment by injection was administered under the supervision of the medical staff by trained leprosy-affected men and women.

Another aspect of the architecture of the asylum at Purulia is evident in the medical focus in the built environment. In the admission wards, treatment by injection was administered under the supervision of the medical staff by trained leprosy-affected men and women. Healthy children born to leprosy-affected parents were also trained as dispensers.

Drug trials of chaulmoogra oil were conducted at Purulia from 1888 and by the beginning of the twentieth century, Purulia was considered to be the leading centre for trails of chaulmoogra and its derivatives. In the 1920s, this treatment, which was supervised by Dr Ernest Muir, generated a great deal of optimism and would be the basis for the establishment of the secular organization, the British Empire Leprosy Relief Association’s (BELRA), which aimed to tackle leprosy within the whole British Empire. (48th Report 32; Pandya) Finally when the sulphones were discovered, Purulia became one of the centres of investigation into their efficacy. (Browne; Muir 171)

The Model Asylum

A closer investigation of leprosy asylums in India defies their reputation as benighted and isolated places. Purulia was a focal point from within which work against leprosy developed into expertise which was disseminated within the international medical community. In other parts of the world, leprosy colonies functioned in similar ways so that by the era in which effective chemotherapies were being developed against leprosy (the 60s and 70s), the links between these “outposts” in Africa, Malaysia, the Philippines, and India were strongly and permanently linked to the centres for medical research in Britain, France, and the USA.

In 1948, the model asylum or leprosarium was described in a Manual of Leprosy by Dr Ernest Muir just on the cusp of the introduction of the sulphones which would ultimately render asylums unnecessary. Its various components were numbered and described, as follows:

- Houses for female patients (Married quarters are between 1 and 2)

- Houses for male patients

- Stores, food distribution, workshops

- Clinic

- Church

- Hall

- Children’s quarters

- Dining-room and kitchen

- Wards for acute cases (Isolation rooms between 9 and 10)

- Chronic wards

- Recreation ground

- Healthy office

- Patients’ office

- Leper staff and well-to-do patients

- Detention room

- The Reverend Uffman with some of the earliest patients, 1906

- Purulia Leprosarium, 1937.

- Purulia Boys’ Home – early cases

- One of the nursery babies at Purulia

- People in Purulia Leprosarium 1937.

- A view from the dressing stations, showing corner of the old hospital (left), covered way to the men’s hospital and the end of the ‘out-patients’ hospital.

- Purulia Leprosarium and Hospital

- Temporary Governor addressing patients at Purulia. In the background, on left, out-patient men. On right, four women, applicants for admission. 1935

- Planting out the seedlings, Purulia.

Notes

*1 In 1906, the total cost of constructions came to Rs 100,000 and the cost of running the asylum was Rs36,000 per year. At this time, in 1896, Rs 1,000 is estimated to be £62. See Bailey, Wellesley. A Visit to Leper Asylums in India and Burma, 1895-96. Edinburgh: Darien Press, 1896, 20.

Sources

Wellesley Bailey, A Glimpse at the Indian Mission-Field and Leper Asylums in 1886-87 (London: John F. Shaw, 1887): 10.

—–, The Lepers of Our Indian Empire: A Visit to Them in 1890-91 (London: John F. Shaw, 1891): 121-4.

S. G. Browne, “The Leprosy Mission: A Century of Service” Leprosy Review 45 (1974): 166-69.

Daniel Cornelius Danielssen, and Carl Wilhelm Boëck, Om Spedalskhed. Christiania 1847, which was translated into French as Traité de la Spedalskhed ou Elephanthiasis des Grecs. Paris 1848.

George Joseph, “’Essentially Christian, Eminently Philanthropic’: the Mission to Lepers in British India”. História, Ciências, Saúde-Manguinhos 10, suppl. 1 (2003): 263-66.

Thomas R Metcalf, “Architecture and the Representation of Empire: India, 1860-1910”, Representations 6 (1984): 58.

Ernest Muir, Manual of Leprosy, (Edinburgh: E & S Livingstone, 1948): 171.

S. S. Pandya, “Ridding the Empire of Leprosy: Sir Leonard Rogers (1868-1962) and the Oil of Chaulmoogra”, unpublished paper.

Report on Leprosy by the Royal College of Physicians, Prepared for, and Published by Her Majesty’s Secretary of State for the Colonies with an Appendix. (London: W H Allen, 1867): Lxix.

Report of a Conference of Leper Asylum Superintendents held at Purulia, Bengal from 18th to 21st February 1908. (Edinburgh: The Darien Press, Bristol Place, 1908): 71.

“Brief Survey of the Fields and Glimpses of the Work”, in The Forty-Sixth Annual Report of the Mission to Lepers. “The Lepers are Cleansed” (London: Mission to Lepers, 1920): 10-11.

“A Fruitful Field” :The Forty-Eighth Annual Report of the Mission to Lepers, (London: Botolph Printing, 1922): 6.

F. D. O. Roberts, “How to Prevent Lepers Migrating from One Asylum to Another, and How to Encourage Inmates to Remain in Asylums” in Report of the Conference of Superintendents of Leper Asylums: The Central Provinces and the Bombay Presidency: Wardha CP, February 1902. (Bombay: Bombay Guardian Mission Press, 1902): 4-6.

Jo Robertson. “Leprosy and the Elusive M leprae: Colonial and Imperial Medical Exchanges in the Nineteenth Century”. História Ciências Saúde: Manguinhos: Leprosy: a Long History of Stigma 10 Supplement 1: (2003):13-40.

—–, “The Leprosy Asylum in India: 1886-1947”. Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences 64.4 (2009): 474-517.

Sir Leonard Rogers and Ernest Muir. Leprosy. 3rd ed. (Bristol: John Wright & Sons, 1946): 126.

Margaret L Sharpe, Cameos from Purulia. London: Mission to Lepers, nd.

Worboys, Michael. “Was there a Bacteriological Revolution in Late Nineteenth-Century Medicine?” Studies in History and Philosophy of Biological and Biomedical Sciences 38 (2007): 20-42.