Leprosy and Identity

A person who was diagnosed with leprosy would find a new identity awaiting for them that triggered off a convergence of social, medical, scientific and legal discursive processes. Stanley Stein expresses this eloquently:

Leprosy! The word was not a diagnosis; it was a pronouncement of doom. My hopes and ambitions were collapsing about me. My future was in ruins. My present? A great cold emptiness …

Leprosy was not just a disease – it was a stigma, a disgrace, a visitation from on high, a punishment for some dreadful sin. What had I done to bring down the wrath of God upon my head? …

Despite the doctor’s kindness and understanding, I left his office convinced that my life was over. I went into the street like a sleepwalker. All the myths and frightening stories I had heard about leprosy rushed through my mind, obliterating the doctor’s reassuring words. I remembered old engravings of lepers carrying a bell. I recalled the scene from Ben Hur and the chilling cry of “Unclean! Unclean!” as the hero’s mother and sister were driven from the city. (Stein 23-4)

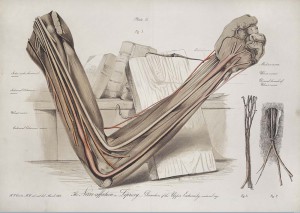

Dissection of the upper extremity of an arm, showing the nerve affected by Leprosy: illustration by Henry Vandyke Carter. Wellcome Library, London. Licensed under CC BY 4.0

In addition to the burden of the historical representation of leprosy, the disease itself destabilised all the usual visual markers of identity, changing one’s physical appearance. M. leprae, the mycobacterium that causes leprosy, enters and damages the peripheral nerves, and before effective medication, the parts of the body that define it and distinguish it, were irrevocably disfigured. The face is particularly important in establishing identity and individuality, and it was often the face that most revealed the damage that leprosy could do. The nose could be affected, eyes clouded over and sight was lost, eyebrows disappeared, the skin thickened with nodules and the quality of the voice would change. Hands and feet were also progressively damaged as a result of repeated injuries to the fingers and toes arising from the loss of sensation that came about from damage to the peripheral nerves.

As leprosy was a disfiguring disease, the loss of physical identity was accompanied by a sense of loss of essential identity, of “humanity” and consequently of legal identity. Carole Rawcliffe notes that although the application of legislation varied and the law was a constantly evolving process, “Anyone who seemed so deformed and terrible of aspect that he or she had to be “put out of the community of mankind” thereby forfeited his or her rights to plead inherit and to make contracts of any kind. (Rawcliffe 271)

As Rawcliffe and, before her, Mary Douglas indicates, “official attempts to separate presumed lepers [sic] from society tended to occur during periods of crisis, when concerns about epidemic disease, disorder and vagrancy were running high.”*1 People with leprosy functioned as trigger points for social frustration, and in the battle for autonomy over their bodies, they could usually only rely on their own efforts to obtain justice. *2

Colonisation and missionary care of people with leprosy brought its own changes to how people were identified. People with leprosy became important to the Imperial project. In Africa, for example, as Megan Vaughan states, “Leprosy offered to the missionaries the possibility of engineering new African communities, isolated from, and expunged of, all those features of African society which they saw as impeding the development of Christianity. In such institutions leprosy patients were offered their identity as a leprosy patient as a ‘liberation’.” (79) She describes the leprosy settlement as a place “where a new identity and new community could be forged.” (83) Ironically, this did produce certain limited freedoms: “Where African patients did self-consciously take on this new identity, they could … exploit all the ambiguities of the European Christian tradition in an attempt to improve their unhappy situation. An apparent compliance could, we are reminded, facilitate resistance at another level.”

To be identified as a “leprosy patient” brought with it certain ambiguities in India, as Buckingham points out. After the 1898 Lepers Act, people sat somewhere uneasily between “prisoner” and “patient.” (Buckingham 51) People were medically cared for as patients and were at the same time confined as prisoners. She explains that this “was more a reflection of the logistical pragmatism of providing food appropriate to Indian tastes on a large scale since vagrant Indian leprosy sufferers formed a substantial majority in the leper hospital.” (56)

But people with leprosy had agency and this increased as medical technologies improved. Kakar argues that some forms of agency would have been “unthinkable in the past, because of strong public prejudice regarding leprosy, also because of low morale of patients, many of whom internalised age-old myths about leprosy.” (Kakar 1) But with the advent of better medical technologies, in the 30s and 40s, “a series of revolts in some leprosy asylums across the country” … “marked a shift from the long pre-history of more muted resistance by patients within the asylums.” (Kakar 2) He argues that “the medical discoveries of the 1920s produced a transformed medical perception of leprosy, which paved the way for a more militant patient protest.” (2) Many local resistances were based on conditions within leprosaria. People protested against religious teaching, medical treatment, and segregation of the sexes. They also flouted the constraints of segregation, although he adds that this form of resistance was understood as a “moral violation.” (9) Crucially, in India, people did not agitate to be allowed to depart from asylums: “… the basic similarity in the incidents that I consider was that patients were adopting more militant postures, and that agitations centered on living conditions in the asylums, not on escape from asylums, nor against confinement … Clearly living conditions outside were not favourable.” As a result of local resistance, “a new and more equal relationship between the patient and the institution had to be forged, which included for the first time a perspective on the rights of patients. This radically new stance on the part of the management allowed leprosy patients a freedom of mobility and of choice which had hitherto been denied …” (76)

In 1920, The Leprosy Mission held a large conference in Calcutta, where superintendents of the various asylums gathered to discuss their work. (Report 1920) At the meeting, Rev Frank Oldrieve expressed the Mission’s plans for people with leprosy in India in the context of an overarching ambition for India. He describes this work as having potential for the whole of India:

We want India to be one of the great nations of the earth. She holds one-fifth of the population of the whole world, and her teeming multitudes will become the people of a great nation, when once they are welded together. And living in this wonderful land we have ideals. I say, we want India to be great commercially, with her vast resources; we want India to be great physically; we want her people to be a healthy people; we want, if possible, to get rid of some of the great scourges that the people have suffered from for centuries – plague, cholera and other diseases, and amongst them leprosy. I say we have ideals for this country, and another great ideal we have is that India shall be one of the leading countries of the earth spiritually. We do believe that India has a very special contribution to make to Christianity …”

The missionary involvement with people with leprosy in India is ideologically harnessed to the imperial project, and the proposed leprosy settlements embody the larger ideal in microcosm. These settlements take as exemplars the model colonies in the Philippines and Hawaii. Warwick Anderson’s “Leprosy and Citizenship” makes connections between the American colonial project and Culion leprosarium. He writes that “To understand the American colonial project it is necessary to study Culion, for the leper colony had become an allegory of the prospects of the macrocolony …” (720) In its utopian benevolence, the Leprosy Mission, addresses its efforts to the physical bodies of Indians, attempting to govern them by regulating their diets, subjecting them to painful and dubious “cures”, separating the sexes so that they cannot produce children, and removing their children from them. These children are transformed into “a band of useful, helpful, healthful citizens contributing constantly to the good of the community” instead of otherwise being “wrecks of humanity through contact continually with leprous fathers and mothers”. They are “saved” in order to be the potential evangelisers of India. One delegate hopes that “If the crown of Hinduism is to be given to Christ, may it not yet be brought forth by the hands of a little child”.

From this then, leprosy not only compromised physical identity, burdened the sufferer with a distasteful representational history, but was also accompanied by a loss of legal status. People were victims of a poorly understood disease that carried a heavy social stigma. People with leprosy became symbolically important to the Imperial project which offered them “liberated” identities that were fraught with ambiguity. In spite of this and all of the ambitions of the Imperial project, people found opportunities to exercise their agency through local resistance, especially as developing medical technologies improved.

Notes

*1 Carole Rawcliffe, Leprosy in Medieval England, p. 253 and Mary Douglas, “Witchcraft and Leprosy: Two Strategies of Exclusion”, Man New Series 26.4 (Dec 1991): 734. There are extensive studies of stigma, for example: Nancy Wexler, “Learning to be a Leper: A Case Study in the Social Construction of Illness” in Social Contexts of Health, Illness, and Patient Care, ed. Elliott G Mishler (New York, 1981), pp. 169-74.

*2 Today, advocacy organisations such as IDEA (International Organisation for Integration, Dignity, and Economic Advancement) promote the rights of leprosy-affected people. http://www.idealeprosydignity.org/

Sources

Sanjiv Kakar, “Medical Developments and Patient Unrest in the Leprosy Asylum, 1860 to 1940” Social Scientist 4-6.24 (1996).

Stanley Stein, Alone No Longer, (Carville, La, 1963), pp. 23-4.

Carole Rawcliffe, Leprosy in Medieval England (Suffolk, UK and Rochester, NY, 2006).

Wellesley C Bailey, The Lepers of Our Indian Empire: A Visit to Them in 1890-91 (London: John F Shaw).

Report of a Conference of Leper Asylum Superintendents and Others on The Leper Problem in India, held in the Town Hall, Calcutta, from the 3rd to 6th February, 1920, under the auspices of the Mission to Lepers (Cuttack: Printed at the Orissa Mission Press, 1920).